Feminist Philosopher을 합성해서 "Femi-sopfer'라는 신조어를 내가 말들었습니다.

페미니스트 철학의 첫 번째 의미는 페미니즘의 배후에 있는 사상과 이론을 묘사하는 것이다.

페미니즘 자체가 매우 다양하기 때문에, 이러한 의미에서 다른 페미니스트 철학이 있다.

자유주의 페미니즘, 급진적 페미니즘, 문화적 페미니즘, 사회주의 페미니즘, 생태페미니즘, 사회 페미니즘 등 페미니즘의 이러한 다양성 각각은 철학적 토대를 가지고 있다.

페미니스트 철학의 두 번째 의미는 철학 분야 내에서 페미니스트 분석을 적용하여 전통주의 철학을 비판하려는 시도를 묘사하는 것이다.

- 다른 종류의 지식보다 이성과 합리성을 강조한다.

- 공격적인 인수 스타일

- 남성 경험을 사용하고 여성 경험을 무시합니다.

다른 페미니스트 철학자들은 이러한 주장들이 적절한 여성적, 남성적 행동의 사회적 규범을 구매하고 받아들이는 것으로 비판한다 : 여성은 또한 합리적이고 합리적이며, 여성은 공격적 일 수 있으며, 모든 남성과 여성의 경험이 동일하지는 않다.

몇몇 페미니스트 철학자들

페미니스트 철학자들의 이러한 예들은 그 문구로 대표되는 아이디어의 다양성을 보여줄 것이다.

Mary Daly는 Boston College에서 33 년 동안 가르쳤습니다. 그녀의 급진적 인 페미니스트 철학 - 그녀가 때때로 그것을 불렀던 신학 -은 전통 종교의 안드로 센트리즘을 비판하고 여성들이 가부장제에 반대 할 수있는 새로운 철학적, 종교적 언어를 개발하려고 노력했다. 그녀는 여성이 남성을 포함한 그룹에서 너무 자주 침묵했기 때문에 그녀의 수업에는 여성 만 포함될 것이고 남성은 개인적으로 가르 칠 수 있다는 그녀의 믿음에 대한 그녀의 입장을 잃었습니다.

가장 잘 알려진 프랑스 페미니스트 중 한 명인 Hélène Cixous는 오이디푸스 단지를 기반으로 한 남성과 여성의 발전을위한 분리 된 경로에 대한 프로이트의 주장을 비판합니다. 그녀는 서양 문화에서 구어체에 대한 서면 단어의 특권 인 로고 센트리즘에 대한 아이디어를 바탕으로 phallogocentrism에 대한 아이디어를 개발했으며, 단순화하기 위해 서양 언어의 바이너리 경향은 여성을 그들이 있거나 가지고있는 것이 아니라 그들이 가지고 있지 않거나 가지고 있지 않은 것에 의해 정의하는 데 사용됩니다.

캐롤 길리건(Carol Gilligan)은 "차이 페미니스트"(남성과 여성 사이에 차이가 있으며 행동을 평등화하는 것이 페미니즘의 목표가 아니라고 주장함)의 관점에서 주장한다. 길리건은 윤리에 대한 그녀의 연구에서 원칙에 기반한 윤리가 윤리적 사고의 가장 높은 형태라고 주장한 전통적인 콜버그 연구를 비판했다. 그녀는 콜버그가 소년들만 연구했으며, 소녀들이 연구될 때, 관계와 보살핌이 원칙보다 그들에게 더 중요하다고 지적했다.

프랑스 레즈비언 페미니스트이자 이론가인 모니크 비티그는 성 정체성과 섹슈얼리티에 대해 썼다. 그녀는 마르크스주의 철학을 비판하고 성별 범주의 폐지를 옹호하면서 "여성"은 "남성"이 존재할 때만 존재한다고 주장했다.

넬 노딩스 (Nel Noddings)는 정의가 아닌 관계에서 윤리 철학을 바탕으로 정의의 접근법이 남성 경험에 뿌리를두고 있으며 여성 경험에 뿌리를 둔 돌보는 접근법에 뿌리를두고 있다고 주장했다. 그녀는 돌보는 접근법이 여성뿐만 아니라 모든 사람들에게 열려 있다고 주장합니다. 윤리적 보살핌은 자연적 보살핌에 의존하고 그것으로부터 자라나지만, 두 가지는 구별됩니다.

Martha Nussbaum은 그녀의 저서 Sex and Social Justice에서 섹스 또는 섹슈얼리티가 권리와 자유에 대한 사회적 결정을 내릴 때 도덕적으로 관련된 구별이라는 것을 부인한다고 주장한다. 그녀는 칸트에 뿌리를 둔 "객관화"라는 철학적 개념을 사용하며 페미니스트 맥락에서 급진적 인 페미니스트 안드레아 드워킨 (Andrea Dworkin)과 캐서린 맥키논 (Catharine MacKinnon)에게 적용되어 개념을보다 완벽하게 정의한다.

일부는 메리 울스턴크래프트를 핵심 페미니스트 철학자로 포함시켜 그 이후에 온 많은 사람들에게 토대를 마련했다.

이하에서 여성주의 철학자 울스터크래프트를 소개합니다.

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/%EC%97%AC%EC%84%B1%EC%A3%BC%EC%9D%98_%EC%B2%A0%ED%95%99

- dhleepaul, 이덕휴 -https://blog.daum.net/dhleepaul/1350

여성주의 철학은 여성주의 관점을 갖는 철학이다. 여성주의 철학은 철학의 텍스트와 방법론 모두에서 여성주의 운동을 지원하고 기존의 철학을 여성주의의 관점에서 비판하고 재구성한다.[1]

세계의 역사에서 여성은 오랫동안 불평등한 처우를 받아왔고, 가부장제와 종교는 이러한 불평등을 심화시켰다. 철학 역시 이러한 틀에서 벗어나지 않아 "남자는 남자의 역할이 있고, 여자는 여자의 역할이 있다"는 주장을 반복하여 왔다.[2] 근대 이전의 철학의 역사 속에서 여성 철학자가 없었던 것은 아니나[주해 1] 여타의 다른 학문과 같이 철학도 오랫동안 여성을 학문의 주체로 인정하지 않았다.[주해 2]

근대에 이르러 사회적 배제와 불평등을 사회구조의 문제로 파악하기 시작하는 사상이 생겨났다. 사회계약론과 같은 계몽주의 사상은 자연권으로서 인권을 주장하였고 이는 〈미국 독립 선언〉과 프랑스 혁명 시기의 〈인간과 시민의 권리 선언〉 등을 통해 선포되었다. 그러나 18세기 말 인권이 보편적 가치라고 확신한 이들 조차 어린이, 광인, 수형자 또는 외국인들은 무능력하기 때문에 정치 참여가 불가하다고 여겼다.[3] 인권 선언을 주창한 사람들의 이러한 배제 대상자 가운데는 여성 또한 포함되어 있었다. 장자크 루소는 《에밀》에서 "성(Sex)을 제외하고는 여성도 남성과 다름없는 인간이지만, 그 성별 차이 때문에 다른 모든 것이 따라온다. 다른 도덕, 다른 교육, 지식과 진리에 이르는 다른 차원, 그리고 남성에게 주어진 것과 다른 사회정치적 기능 등등 …"[4]과 같이 서술하여 여성을 남성보다 열등한 조재로 묘사하였다. 루소는 성분업을 정당화하는 젠더 담론으로 여성에 대한 억압을 정당화하였다.[5] 한편, 루소와 동시대인이었던 메리 울스턴크래프트(Mary Wollstonecraft, 1757년 - 1797년)는 루소의 이러한 주장에 대해 자연권이 내세우는 평등과 인권에 어긋나는 비합리적인 것이라고 비판하였고, 그의 저서 《여성의 권리 옹호》[주해 3] 가운데 많은 부분을 루소의 주장을 반박하는데 할애하였다.[6]

여성주의 철학은 여권 신장 운동과 함께 발전하여 왔다. 제일 먼저 부각된 것은 참정권의 문제로 여성주의 운동가들은 민주주의의 근간을 이루는 참정권 행사에 여성을 배제하는 것에 맞서 오랫동안 투쟁하였다. 프랑스에서 여성의 참정권이 제일 먼저 논의된 것은 1900년 국민회의였고, 1919년 하원을 통과하였으나 상원에 의해 부결되었다. 프랑스에서 여성 참정권이 보장된 것은 1945년이 되어서였다.[7] 러시아는 러시아 혁명의 여파로 비교적 이른 시기인 1917년 여성의 투표권을 인정하였다.[8] 미국에서는 1919년이 되어서야 백인 여성에 대한 참정권이 주어졌으나[9] "유색인종"을 포함하는 모든 여성에게 참정권이 부여된 것은 1965년이 되어서였다.[10] 영국에서는 1928년이 되어서야 여성에게 남성과 동등한 참정권이 인정되었다.[11] 국가가 아닌 조직에서 의사 결정 구조에 여성의 참여를 배제하는 것은 오늘날에도 여전히 문제가 되고 있다. 대한민국에서 한국YMCA가 여성 회원에 대해 총회원의 자격을 주지 않은 것이 위법하다는 판결이 난 것은 2009년의 일이었다.[12]

한편, 20세기 초에 이르기까지 여성성에 대한 논의는 주로 생물학적 성 구분에 기댄 것이었다. 1949년 출간된 시몬 드 보부아르(Simone de Beauvoir, 1908년 - 1986년)의 《제2의 성》[주해 4]은 여성주의의 새로운 장을 열었다는 평가를 받는다.[13] 보부아르는 이 책에서 생물학적 성(Sex)과 사회적 성(Gender)[주해 5]을 명확히 구분하고 여성에게 강요되는 성 역할은 생물학적인 것때문이 아니라 사회적인 것이라고 주장하였다.[14] 즉, 여성은 생물학적으로 그렇게 태어났기 때문이 아니라 남성중심적 사회의 시각을 통해 "남성이 아닌" 타자(他者)로 만들어진 여성성을 내면화 하게 된다는 것이다.[15] 이러한 의미에서 보부아르는 "여성은 태어나는 것이 아니라 만들어진다"고 하였다.[16]

보부아르 이후의 여성주의는 여러 다른 사상들로 분화되었다. 이들은 이전 시기 제1세대 여성주의가 벌인 참정권 운동과는 다른 흐름을 형성한다는 의미에서 여성주의의 "제2의 물결"이라고 불린다.[17] 오늘날 여성주의의 갈래는 크게 보아 자유주의적 여성주의, 마르크스주의 여성주의, 급진적 여성주의, 사회주의적 여성주의, 생태여성주의 등이 있으며[18], 실존주의, 자크 라캉, 해체주의, 포스트구조주의, 포스트모더니즘과 같은 다양한 철학 사조 역시 여성주의 철학과 영향을 주고받는다.[5]

주요 논점[편집]

여성주의 철학은 철학 일반이 다루는 모든 범주에 대해 여성주의 관점에서 비판과 재구성을 수행한다. 그 가운데서도 다음의 항목들은 여성주의 철학의 대표적인 주제이다.[주해 6]

- 성과 젠더의 구분

- 여성성 - 사회학적 여성성, 심리학적 여성성 등

- 성 역할과 가족 제도 - 가부장제, 모성 등

- 노동과 여성 - 여성과 가정노동, 산업사회와 여성 노동 등

- 권력과 여성 - 여성과 정치활동, 정치제도 등

사조[편집]

여성주의는 여러가지 사회적 상황과 종교 신념 성/젠더의 역할 등에 따른 생각에 의해 수 많은 사조를 보이고 있다. 그 가운데 철학과 관련이 깊은 사조들로는 다음과 같은 것들이 있다.

- 개인주의적 여성주의

- 급진적 여성주의

- 마르크스주의 여성주의

- 사회주의적 여성주의

- 생태여성주의

- 실존주의 여성주의

- 보수여성주의

- 분석여성주의

- 아나코 여성주의

- 자유주의적 여성주의

- 포스트구조주의적 여성주의

- 포스트모던 여성주의

- 해체주의 여성주의

주요 사상가[편집]

- 로레인 코드

- 뤼스 이리가레

- 린다 마틴 알코프

- 마사 누스바움

- 메리 울스턴크래프트

- 미란다 프리커

- 샐리 허슬랭거

- 시몬 드 보부아르

- 아이리스 멕리언 영

- 앨리슨 재거

- 올랭프 드 구주

- 우마 나라얀

- 존 스튜어트 밀

- 주디스 버틀러

- 쥘리아 크리스테바

- 케서린 켈러

- 클라우디아 카드

참고 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Wollstonecraft

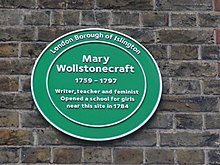

Mary Wollstonecraft (/ˈwʊls t ən k r æ f t/, also UK: /-krɑːft/; [1] 1759년 4월 27일 - 1797년 9월 10일)은 영국의 작가, 철학자, 여성 권리 옹호자였다. 20세기 후반까지만 해도 당시 여러 가지 틀에 얽매이지 않는 개인적 관계를 아우르던 울스턴크래프트의 삶은 그녀의 글보다 더 많은 주목을 받았다. 오늘날 울스턴크래프트는 건국의 페미니스트 철학자 중 한 명으로 여겨지고 있으며, 페미니스트들은 종종 그녀의 삶과 작품을 중요한 영향으로 인용한다.

그녀의 짧은 경력 동안, 그녀는 소설, 논문, 여행 서사, 프랑스 혁명의 역사, 행동 서적 및 어린이 책을 썼습니다. 울스턴크래프트(Wollstonecraft)는 여성의 권리에 대한 변증(A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792)으로 가장 잘 알려져 있는데, 그녀는 여성이 자연적으로 남성보다 열등하지는 않지만 교육이 부족하기 때문인 것처럼 보인다고 주장한다. 그녀는 남성과 여성 모두 이성적인 존재로 취급되어야하며 이성에 기초한 사회 질서를 상상해야한다고 제안합니다.

울스턴크래프트가 사망한 후, 그녀의 미망인은 그녀의 삶에 대한 회고록(1798)을 출판하여 거의 한 세기 동안 우연히 그녀의 명성을 파괴한 그녀의 비정통적인 생활 방식을 드러냈다. 그러나 이십 세기가 바뀌면서 페미니스트 운동이 출현함에 따라 울스턴크래프트의 여성 평등에 대한 옹호와 전통적인 여성성에 대한 비판이 점점 더 중요해졌다.

헨리 퓌셀리와 길버트 임레이(딸 패니 임레이를 낳았음)와 함께 두 차례의 불행한 일을 겪은 후, 울스턴크래프트는 아나키스트 운동의 선조 중 한 명인 철학자 윌리엄 고드윈과 결혼했다. 울스턴크래프트는 38세의 나이로 사망하여 미완성 원고를 몇 개 남겼다. 그녀는 두 번째 딸 메리 셸리를 낳은 지 11 일 만에 사망했으며, 그는 뛰어난 작가이자 프랑켄슈타인의 작가가 될 것입니다.

전기

초기 생애

울스턴크래프트는 1759년 4월 27일 런던 스피탈필드에서 태어났다. [2] 그녀는 엘리자베스 딕슨과 에드워드 존 울스턴크래프트의 일곱 자녀 중 둘째였다. [3] 그녀가 어렸을 때 그녀의 가족은 편안한 수입을 가졌지 만, 그녀의 아버지는 점차적으로 투기 프로젝트에 그것을 낭비했다. 결과적으로, 가족은 재정적으로 불안정 해졌고 울스턴크래프트의 젊은 시절에 자주 이사를 강요 받았다. [4] 가족의 재정 상황은 결국 너무 심각 해져서 Wollstonecraft의 아버지는 그녀가 성숙 할 때 상속받을 돈을 넘겨 주도록 강요했습니다. 더욱이, 그는 술에 취한 분노로 아내를 때리는 폭력적인 남자였습니다. 십대 시절, 울스턴크래프트는 그녀를 보호하기 위해 어머니의 침실 문 밖에 누워 있었다. [5] 울스턴크래프트는 평생 동안 언니인 에버리나와 엘리자에게도 비슷한 모성 역할을 했다. 1784년의 결정적인 순간에, 그녀는 아마도 산후 우울증을 앓고 있던 엘리자를 설득하여 남편과 유아를 떠나게 했다. 울스턴크래프트는 엘리자가 도망칠 수 있도록 모든 준비를 마쳤으며, 사회적 규범에 도전하려는 의지를 보여주었다. 그러나 그녀의 여동생은 사회적 비난을 받았고 재혼 할 수 없었기 때문에 가난과 노력의 삶을 살 운명에 처하게되었습니다. [6]

두 번의 우정이 울스턴크래프트의 초기 삶을 형성했다. 첫 번째는 베벌리의 제인 아덴과 함께했다. 두 사람은 자주 함께 책을 읽고 자기 스타일의 철학자이자 과학자 인 Arden의 아버지가 발표 한 강의에 참석했습니다. 울스턴크래프트는 아덴 가문의 지적 분위기에 환호했고, 아덴과의 우정을 매우 소중히 여겼고, 때로는 감정적으로 소유욕을 가질 정도였다. Wollstonecraft는 그녀에게 다음과 같이 썼다 : "나는 우정에 대한 낭만적 인 개념을 형성했다 ... 나는 사랑과 우정에 대한 나의 생각에서 조금 특이하다. 나는 첫 번째 장소를 가져야하거나 아무것도하지 않아야한다. " [7] 울스턴크래프트가 아덴에게 보낸 편지 중 일부에서, 그녀는 평생 동안 그녀를 괴롭힐 휘발성 있고 우울한 감정을 드러낸다. [8] 두 번째이자 더 중요한 우정은 패니 (프랜시스) 블러드와 함께, 그녀에게 부모의 인물이 된 Hoxton의 부부 인 Clares에 의해 Wollstonecraft에 소개되었습니다. 울스턴크래프트는 블러드가 마음을 열었다고 인정했다. [9]

그녀의 가정 생활에 불만을 품은 울스턴크래프트는 1778년 홀로 파업을 벌였고, 바스에 사는 미망인 사라 도슨(Sarah Dawson)의 숙녀 동반자로 일자리를 구했다. 그러나 Wollstonecraft는 불가사의 한 여성과 어울리는 데 어려움을 겪었습니다 (딸 교육에 대한 생각, 1787에서 그러한 위치의 단점을 설명 할 때 그녀가 그린 경험). 1780 년에 그녀는 죽어가는 어머니를 돌보기 위해 다시 부름을 받고 집으로 돌아 왔습니다. [10] 어머니의 죽음 이후 도슨의 직장으로 돌아가기보다는, 울스턴크래프트는 블러드와 함께 이사했다. 그녀는 가족과 함께 보낸 두 해 동안 울스턴크래프트보다 전통적인 여성 가치에 더 많은 투자를 한 블러드를 이상화했다는 것을 깨달았다. 그러나 울스턴크래프트는 평생 동안 패니와 그녀의 가족에게 헌신적이었으며, 블러드의 동생에게 금전적 도움을 자주 주었다. [11]

울스턴크래프트는 피를 가진 여성 유토피아에서 사는 것을 상상했다. 그들은 함께 방을 임대하고 정서적으로나 재정적으로 서로를 지원할 계획을 세웠지 만,이 꿈은 경제적 현실 하에서 무너졌습니다. Wollstonecraft, 그녀의 자매 및 Blood는 생계를 유지하기 위해 반대 공동체 인 Newington Green에 함께 학교를 설립했습니다. 피는 곧 약혼하게되었고, 결혼 후 남편 휴 스키와 함께 리스본 포르투갈로 이사하여 항상 불안정했던 그녀의 건강을 향상시킬 수 있기를 희망했습니다. [12] 주변 환경의 변화에도 불구하고 블러드의 건강은 그녀가 임신했을 때 더욱 악화되었고, 1785 년 울스턴크래프트는 학교를 떠나 블러드를 따라 그녀를 간호했지만 아무 소용이 없었다. [13] 더욱이, 그녀의 학교 포기는 실패로 이어졌다. [14] 블러드의 죽음은 울스턴크래프트를 황폐화시켰고, 그녀의 첫 번째 소설 《메리: 픽션》(1788)의 영감의 일부였다. [15]

'새로운 속의 첫 번째'

1785년 블러드가 사망한 후, 울스턴크래프트의 친구들은 그녀가 아일랜드에 있는 앵글로-아일랜드 킹스버러 가문의 딸들의 통치권으로 자리를 잡는 것을 도왔다. 비록 그녀가 킹스버러 여사와 잘 지낼 수는 없었지만,[16] 아이들은 그녀에게 영감을 주는 강사를 찾았다. 딸 중 한 명인 마가렛 킹은 나중에 그녀가 '모든 미신으로부터 마음을 해방시켰다'고 말할 것이다. [17] 올해 울스턴크래프트의 경험 중 일부는 그녀의 유일한 어린이 책인 《실생활의 원작》(Original Stories from Real Life, 1788)에 들어갈 것이다. [18]

존경 받지만 가난한 여성들에게 열려있는 제한된 직업 옵션에 좌절감을 느낀 울스턴크래프트는 '여성의 불행한 상황, 유행적으로 교육받고 행운없이 남겨진 여성의 불행한 상황'이라는 제목의 딸 교육에 대한 생각의 장에서 웅변적으로 묘사 한 장애물 - 그녀는 통치로서 불과 일 년 만에 작가로서의 경력을 시작하기로 결정했습니다. 이것은 급진적 인 선택이었습니다.왜냐하면 당시에는 글쓰기를 통해 자신을 지원할 수있는 여성이 거의 없었기 때문입니다. 그녀가 1787년 여동생 에베리나에게 편지를 썼을 때, 그녀는 '새로운 속의 첫 번째'가 되려고 노력했다. [19] 그녀는 런던으로 이주했고, 자유주의 출판사 조셉 존슨의 도움을 받아 자신을 부양하기 위해 살고 일할 곳을 찾았다. [20] 그녀는 프랑스어와 독일어를 배웠고 텍스트를 번역했으며,[21] 특히 자크 네커의 종교적 의견의 중요성과 도덕의 요소, 기독교 고틸프 살츠만의 어린이 사용에 관한 것이다. 그녀는 또한 존슨의 정기 간행물 인 분석 리뷰에 대한 소설을 주로 썼습니다. 울스턴크래프트의 지적 우주는 이 시기에 그녀가 리뷰를 위해 했던 독서뿐만 아니라 그녀가 간직한 회사로부터도 확장되었다: 그녀는 존슨의 유명한 만찬에 참석했고, 급진적 팜플렛티어인 토마스 페인과 철학자 윌리엄 고드윈을 만났다. Godwin과 Wollstonecraft가 처음 만났을 때, 그들은 서로에게 실망했습니다. 고드윈은 페인의 말을 들으러 왔지만, 울스턴크래프트는 거의 모든 주제에 대해 동의하지 않고 밤새도록 그를 공격했다. 그러나 존슨 자신은 친구 이상이되었습니다. 그녀는 편지에서 그를 아버지와 형제로 묘사했습니다. [22]

런던에서 울스턴크래프트는 사우스워크의 돌벤 스트리트(Dolben Street)에 살았다. 1769 년 최초의 Blackfriars Bridge가 개통 된 후 떠오르는 지역. [23]

런던에 있는 동안, 울스턴크래프트는 이미 결혼했음에도 불구하고 예술가 헨리 퓨즐리와 관계를 맺었다. 그녀는 그의 천재성, '그의 영혼의 웅장함, 이해의 신속성, 그리고 사랑스러운 동정심'에 매료되어 있다고 썼다. [24] 그녀는 퓌셀리와 그의 아내와 플라토닉 생활 협정을 제안했지만, 후셀리의 아내는 소름이 끼쳤고, 그는 울스턴크래프트와의 관계를 끊었다. [25] Fuseli가 거절 한 후, Wollstonecraft는 사건의 굴욕에서 벗어나 최근 남성의 권리 옹호 (1790)에서 방금 축하 한 혁명적 인 사건에 참여하기 위해 프랑스로 여행하기로 결정했습니다. 그녀는 Whig MP Edmund Burke의 프랑스 혁명에 대한 프랑스 혁명 (1790)에 대한 정치적으로 보수적 인 비판에 대한 응답으로 남성의 권리를 썼으며 하룻밤 사이에 그녀를 유명하게 만들었습니다. 프랑스 혁명에 대한 고찰은 1790년 11월 1일에 출판되었고, 울스턴크래프트를 너무 화나게 하여 그녀는 한 달의 나머지 시간을 그녀의 반박문을 썼다. 1790년 11월 29일 《명예로운 에드먼드 버크에게 보내는 편지》에서 《남성의 권리에 대한 증거》가 처음 익명으로 출판되었다. [26] 인간의 권리에 대한 증거의 두 번째 판은 12 월 18 일에 출판되었으며, 이번에는 출판사가 Wollstonecraft를 저자로 공개했습니다. [26]

Wollstonecraft called the French Revolution a 'glorious chance to obtain more virtue and happiness than hitherto blessed our globe'.[27] Against Burke's dismissal of the Third Estate as men of no account, Wollstonecraft wrote, 'Time may show, that this obscure throng knew more of the human heart and of legislation than the profligates of rank, emasculated by hereditary effeminacy'.[27] About the events of 5–6 October 1789, when the royal family was marched from Versailles to Paris by a group of angry housewives, Burke praised Queen Marie Antoinette as a symbol of the refined elegance of the ancien régime, who was surrounded by 'furies from hell, in the abused shape of the vilest of women'.[27] Wollstonecraft by contrast wrote of the same event: 'Probably you [Burke] mean women who gained a livelihood by selling vegetables or fish, who never had any advantages of education'.[27]

Wollstonecraft was compared with such leading lights as the theologian and controversialist Joseph Priestley and Paine, whose Rights of Man (1791) would prove to be the most popular of the responses to Burke. She pursued the ideas she had outlined in Rights of Men in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), her most famous and influential work.[28] Wollstonecraft's fame extended across the English channel, for when the French statesmen Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord visited London in 1792, he visited her, during which she asked that French girls be given the same right to an education that French boys were being offered by the new regime in France.[29]

France

Wollstonecraft left for Paris in December 1792 and arrived about a month before Louis XVI was guillotined. Britain and France were on the brink of war when she left for Paris, and many advised her not to go.[30] France was in turmoil. She sought out other British visitors such as Helen Maria Williams and joined the circle of expatriates then in the city.[31] During her time in Paris, Wollstonecraft associated mostly with the moderate Girondins rather than the more radical Jacobins.[32] It was indicative that when Archibald Hamilton Rowan, the United Irishman, encountered her in the city in 1794 it was at a post-Terror festival in honour of the moderate revolutionary leader Mirabeau, who had been a great hero for Irish and English radicals before his death (from natural causes) in April 1791.[33]

1792년 12월 26일, 울스턴크래프트는 전 국왕 루이 XVI가 국회 앞에서 재판을 받는 것을 보았고, 놀랍게도 루이가 그의 성격에서 기대했던 것보다 더 위엄 있게 앉아 있는 것을 보았을 때, 죽음을 맞이할 해크니 코치를 만났을 때, 내 눈에서 무의미하게 눈물이 흘러나오는 것을 발견했다. 그의 종족 중 그토록 많은 이가 승리한 곳'. [32]

프랑스는 1793년 2월 영국에 전쟁을 선포했다. 울스턴크래프트는 프랑스를 떠나 스위스로 가려고 했으나 허락을 받지 못했다. [34] 3월에, 자코뱅이 지배하는 공공 안전위원회가 권력을 잡았고, 최초의 '총체적 전쟁'을 위해 프랑스를 동원하기 위한 전체주의 정권을 창설했다.

프랑스의 외국인들에게는 삶이 매우 어려워졌습니다. [35] 처음에 그들은 경찰의 감시를 받았고, 거주 허가를 받기 위해 프랑스인들로부터 공화국에 대한 충성심을 증언하는 여섯 개의 서면 진술서를 작성해야했습니다. 그 후 1793년 4월 12일, 모든 외국인은 프랑스를 떠나는 것이 금지되었다. [36] 혁명에 대한 그녀의 동정심에도 불구하고, 울스턴크래프트의 삶은 지론딘들이 자코뱅인들에게 길을 잃어버렸기 때문에 더욱 불편해진다. [36] 울스턴크래프트의 프랑스 친구들 중 일부는 자코뱅이 적들을 몰살하기 위해 나섰을 때 단두대에 머리를 잃었다. [36]

길버트 임레이, 테러의 통치, 그리고 그녀의 첫 아이

방금 여성의 권리를 쓴 Wollstonecraft는 자신의 아이디어를 시험해보기로 결심했고, 프랑스 혁명의 자극적 인 지적 분위기 속에서 그녀는 가장 실험적인 낭만적 인 애착을 시도했습니다 : 그녀는 미국의 모험가 인 길버트 임레이 (Gilbert Imlay)와 열정적으로 만나 사랑에 빠졌습니다. 울스턴크래프트는 결혼하지 않았음에도 불구하고 임레이와 함께 잠을 자면서 자신의 원칙을 실천에 옮겼는데, 이는 '존경받을만한' 영국 여성의 용납할 수 없는 행동이었다. [36]그녀가 결혼에 관심이 있든 없든, 그는 그렇지 않았고, 그녀는 그 남자의 이상화와 사랑에 빠진 것처럼 보인다. 여성의 권리에서 관계의 성적 구성 요소에 대한 거부에도 불구하고, 울스턴크래프트는 임레이가 섹스에 대한 관심을 일깨웠다는 것을 발견했다. [37]

울스턴크래프트는 프랑스에서 본 것에 어느 정도 환멸을 느꼈고, 공화국 하의 사람들은 정부가 '독한' '잔인한' 상태로 남아 있는 동안 권력을 잡은 사람들에게 여전히 노예처럼 행동했다고 썼다. [35] 그녀의 환멸에도 불구하고, 울스턴크래프트는 이렇게 썼다:

나는 유럽에 더 공정한 날이 밝아오고 있다는 희망을 아직 포기할 수 없으며, 비록 내가 주저없이 관찰해야하지만, 모든 곳에서 귀족 [귀족]의 명예의 요점을 제쳐두고있는 것처럼 보이는 좁은 상업 원칙에서 기대할 수있는 것은 거의 없다. 직분에 대한 동일한 자존심 때문에, 권력에 대한 동일한 욕망이 여전히 보인다. 이러한 악화와 함께, 모호함으로 돌아가는 것을 두려워하면서, 구별을 위해 유물을 얻었지만 얻은 후에, 각 영웅 또는 철학자는 모두가이 새로운 제목으로 더빙되기 때문에, 태양이 비치는 동안 건초를 만들려고 노력합니다. [35]

울스턴크래프트는 자코뱅스가 여성을 대하는 것에 불쾌감을 느꼈다. 그들은 여성들에게 동등한 권리를 부여하는 것을 거부하고, '아마존'을 비난했으며, 여성들은 장자크 루소의 남성에 대한 도우미 이상에 부합해야한다는 것을 분명히했다. [38] 1793년 10월 16일, 마리 앙투아네트는 단두대에 올랐다. 그녀의 혐의와 유죄 판결 중에서, 그녀는 아들과 근친상간을 저지른 혐의로 유죄 판결을 받았다. [39] 울스턴크래프트는 전 여왕을 싫어했지만, 자코뱅이 마리 앙투아네트의 비뚤어진 성행위가 프랑스 국민들이 그녀를 미워하는 주된 이유 중 하나로 만들 것이라고 우려했다. [38]

테러 통치의 일일 체포와 처형이 시작되면서 울스턴크래프트는 의혹을 받았다. 그녀는 결국 지론딘을 이끄는 친구로 알려진 영국 시민이었습니다. 1793년 10월 31일, 지론딘 지도자들 대부분은 단두대에 올랐다. 임레이가 울스턴크래프트에게 소식을 전했을 때, 그녀는 기절했다. [39] 이 무렵, 임레이는 부족을 야기하고 인플레이션을 악화시켰던 프랑스의 영국 봉쇄를 이용하고 있었다.[38] 선박을 전세하여 미국으로부터 음식과 비누를 가져오고 영국 왕립 해군을 피함으로써 여전히 돈이 있는 프랑스인들에게 프리미엄으로 팔 수 있는 물품들을 피했다. 임레이의 봉쇄 작전은 일부 자코뱅의 존경과 지지를 얻었고, 그가 바라던 대로 테러 기간 동안 그의 자유를 보장했다. [40] 울스턴크래프트가 체포되는 것을 막기 위해, 임레이는 파리에 있는 미국 대사관에 그가 그녀와 결혼했다는 거짓 진술을 했고, 자동적으로 그녀를 미국 시민으로 만들었다. [41]그녀의 친구들 중 몇몇은 그렇게 운이 좋지 않았다. 토마스 페인 (Thomas Paine)과 같은 많은 사람들이 체포되었고 일부는 단두대에 갇혔습니다. 그녀의 자매들은 그녀가 투옥되었다고 믿었습니다. [인용 필요]

울스턴크래프트는 자코뱅 밑의 삶을 '악몽'이라고 불렀다. 거대한 주간 퍼레이드가 있었는데, 모든 사람들이 공화국에 대한 부적절한 헌신으로 의심 받지 않도록 자신을 보여주고 음탕하게 응원하고, 야간 경찰이 '공화국의 적'을 체포하기 위해 습격했습니다. [36] 1794년 3월 그녀의 여동생 에버리나에게 보낸 편지에서 울스턴크래프트는 이렇게 적었다.

내가 목격 한 슬픈 장면이 내 마음에 남긴 인상에 대해 당신이 아는 것은 불가능합니다 ... 죽음과 비참함은, 모든 형태의 테루르에서, 이 헌신적인 나라를 뒤덮고 있다―나는 프랑스에 온 것이 분명 기쁘다, 왜냐하면 나는 이제껏 기록된 가장 비범한 사건에 대한 정당한 의견을 결코 가질 수 없었기 때문이다. [36]

울스턴크래프트는 곧 임레이에게 임신을 하게 되었고, 1794년 5월 14일 그녀는 첫 아이인 패니를 낳았고, 아마도 그녀의 가장 친한 친구의 이름을 따서 이름을 지었다. [42] 울스턴크래프트는 너무 기뻐했다. 그녀는 친구에게 '내 어린 소녀가 너무 남자답게 빨기 시작해서 그녀의 아버지는 여자의 R[igh]ts의 두 번째 부분을 쓰는 것에 대해 뻔뻔스럽게 생각한다'고 썼다. [43] 그녀는 임신과 외국에서 혼자 새로운 어머니가되는 부담뿐만 아니라 프랑스 혁명의 소동이 커지고 있음에도 불구하고 계속해서 열렬한 글을 썼다. 프랑스 북부의 르 아브르 (Le Havre)에서 그녀는 초기 혁명의 역사, 프랑스 혁명의 역사적, 도덕적 견해 (An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution)를 썼으며, 1794 년 12 월 런던에서 출판되었습니다. [44] 임레이는 국내 정신과 모성 울스턴크래프트에 불만을 품고 결국 그녀를 떠났다. 그는 르아브르에서 그녀와 패니에게 돌아갈 것이라고 약속했지만, 그녀에게 편지를 쓰는 것이 지연되고 오랜 부재로 인해 울스턴크래프트는 다른 여자를 찾았다는 확신을 갖게 되었다. 그에게 보낸 그녀의 편지는 궁핍한 추방으로 가득 차 있는데, 대부분의 비평가들은 심하게 우울한 여성의 표현으로 묘사하는 반면, 다른 사람들은 좋은 친구들이 투옥되거나 처형되는 것을 보았던 혁명의 한가운데에 유아와 함께 홀로 외국 여성이었던 그녀의 상황에서 비롯된 것이라고 말한다. [45]

자코뱅의 몰락과 프랑스 혁명의 역사적, 도덕적 견해

1794년 7월, 울스턴크래프트는 자코뱅의 몰락을 환영하면서, 프랑스에서 언론의 자유가 회복될 것이라고 예측했고, 이로 인해 그녀는 파리로 돌아갔다. [36] 1794년 8월, 임레이는 런던으로 떠나 곧 돌아오겠다고 약속했다. [36] 1793년에, 영국 정부는 급진주의자들에 대한 단속을 시작하였고, 시민의 자유를 정지시키고, 과감한 검열을 가하고, 혁명에 동조하는 것으로 의심되는 사람을 반역하려고 시도했고, 이로 인해 울스턴크래프트는 그녀가 돌아오면 감옥에 갇히게 될까봐 두려워하게 되었다. [34]

1794-95년의 겨울은 한 세기가 넘는 기간 동안 유럽에서 가장 추운 겨울이었으며, 이로 인해 울스턴크래프트와 딸 패니는 절망적인 상황에 처하게 되었다. [46] 세느강은 그 해 겨울에 얼어붙었고, 이로 인해 배들이 파리에 식량과 석탄을 가져올 수 없게 되었고, 이로 인해 도시의 추위로 인한 굶주림과 사망이 만연했다. [47] 울스턴크래프트는 임레이에게 편지를 계속 써서 즉시 프랑스로 돌아가라고 요청하면서, 그녀는 여전히 혁명에 대한 믿음이 있고 영국으로 돌아가고 싶지 않다고 선언했다. [34] 1795년 4월 7일 프랑스를 떠난 후, 그녀는 아이에게 정당성을 부여하기 위해 자신을 '임레이 부인'이라고 계속 불렀다. [48]

영국의 역사가 톰 푸르니스(Tom Furniss)는 프랑스 혁명에 대한 역사적, 도덕적 관점(An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution)을 울스턴크래프트의 책 중 가장 소홀히 한 책이라고 불렀다. 그것은 1794 년 런던에서 처음 출판되었지만 두 번째 판은 1989 년까지 나타나지 않았습니다. [34] 후대는 Furniss가 그녀를 '최고의 작품'이라고 불렀던 프랑스 혁명에 대한 그녀의 설명보다 그녀의 페미니스트 저술에 더 관심이있었습니다. [34] 울스턴크래프트는 역사가로서 훈련을 받지 못했지만, 프랑스의 평범한 사람들이 혁명에 어떻게 반응했는지를 설명하는 모든 종류의 저널, 편지 및 문서를 사용했다. 그녀는 Furniss가 영국의 '히스테리 적'반 혁명 분위기라고 불렀던 것에 대항하려고 노력하고있었습니다.이 분위기는 혁명을 프랑스 국가 전체가 미쳐 버린 것으로 묘사했습니다. [34] 울스턴크래프트는 대신 혁명이 1789년 프랑스를 사로잡은 위기에서 벗어나지 못한 일련의 사회적, 경제적, 정치적 조건들로부터 발생했다고 주장했다. [34]

프랑스 혁명에 대한 역사적, 도덕적 견해는 울스턴크래프트에게 어려운 균형 잡힌 행동이었다. 그녀는 자코뱅 정권과 테러의 통치를 비난했지만, 동시에 그녀는 혁명이 위대한 업적이라고 주장하면서 1793-94 년의 테러에 대해 글을 쓰기보다는 1789 년 후반에 그녀의 역사를 멈추게했다. [49] 에드먼드 버크 (Edmund Burke)는 1789 년 10 월 5-6 일 파리에서 온 여성 그룹이 프랑스 왕실을 베르사유 궁전에서 파리로 강제 강제 파견 한 사건과 관련하여 프랑스 혁명에 대한 그의 고찰을 끝냈다. [50] 버크는 여성들을 '지옥에서 온 분노'라고 불렀고, 울스턴크래프트는 가족을 먹일 빵이 부족하다는 것에 분노한 평범한 주부들로서 그들을 변호했다. [34] 버크가 폭도들의 고귀한 희생자인 마리 앙투아네트의 이상화된 초상화에 맞서, 울스턴크래프트는 여왕을 팜므 파탈, 매혹적이고 속이는 위험한 여성으로 묘사했다. [51] 울스턴크래프트는 귀족의 가치관이 군주제에서 여성을 타락시켰다고 주장했는데, 왜냐하면 그러한 사회에서 여성의 주된 목적은 왕조를 계속하기 위해 아들을 낳는 것이었고, 이는 본질적으로 여성의 가치를 자궁으로만 감소시켰기 때문이다. [51] 더욱이, 울스턴크래프트는 여왕이 왕비를 거느리지 않는 한, 대부분의 여왕은 여왕 컨소시엄이었으며, 이는 여성이 남편이나 아들을 통해 영향력을 행사해야 한다는 것을 의미하며, 그녀가 점점 더 교활해지도록 격려해야 한다고 지적했다. 울스턴크래프트는 귀족적 가치관이 여성의 몸과 그녀의 마음과 성격에 매력을 느낄 수 있는 능력을 강조함으로써 마리 앙투아네트와 같은 여성들이 조작적이고 무자비하게 부추겨 여왕을 앙시앙 레짐의 부패하고 부패한 산물로 만들었다고 주장했다. [51]

In Biographical Memoirs of the French Revolution (1799) the historian John Adolphus, F.S.A., condemned Wollstonecraft's work as a 'rhapsody of libellous declamations' and took particular offense at her depiction of King Louis XVI.[52]

England and William Godwin

Seeking Imlay, Wollstonecraft returned to London in April 1795, but he rejected her. In May 1795 she attempted to commit suicide, probably with laudanum, but Imlay saved her life (although it is unclear how).[53] In a last attempt to win back Imlay, she embarked upon some business negotiations for him in Scandinavia, trying to locate a Norwegian captain who had absconded with silver that Imlay was trying to get past the British blockade of France. Wollstonecraft undertook this hazardous trip with only her young daughter and Marguerite, her maid. She recounted her travels and thoughts in letters to Imlay, many of which were eventually published as Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark in 1796.[54] When she returned to England and came to the full realisation that her relationship with Imlay was over, she attempted suicide for the second time, leaving a note for Imlay:

Let my wrongs sleep with me! Soon, very soon, shall I be at peace. When you receive this, my burning head will be cold ... I shall plunge into the Thames where there is the least chance of my being snatched from the death I seek. God bless you! May you never know by experience what you have made me endure. Should your sensibility ever awake, remorse will find its way to your heart; and, in the midst of business and sensual pleasure, I shall appear before you, the victim of your deviation from rectitude.[55]

She then went out on a rainy night and "to make her clothes heavy with water, she walked up and down about half an hour" before jumping into the River Thames, but a stranger saw her jump and rescued her.[56] Wollstonecraft considered her suicide attempt deeply rational, writing after her rescue,

I have only to lament, that, when the bitterness of death was past, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But a fixed determination is not to be baffled by disappointment; nor will I allow that to be a frantic attempt, which was one of the calmest acts of reason. In this respect, I am only accountable to myself. Did I care for what is termed reputation, it is by other circumstances that I should be dishonoured.[57]

Gradually, Wollstonecraft returned to her literary life, becoming involved with Joseph Johnson's circle again, in particular with Mary Hays, Elizabeth Inchbald, and Sarah Siddons through William Godwin. Godwin and Wollstonecraft's unique courtship began slowly, but it eventually became a passionate love affair.[58] Godwin had read her Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark and later wrote that "If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration."[59] Once Wollstonecraft became pregnant, they decided to marry so that their child would be legitimate. Their marriage revealed the fact that Wollstonecraft had never been married to Imlay, and as a result she and Godwin lost many friends. Godwin was further criticised because he had advocated the abolition of marriage in his philosophical treatise Political Justice.[60] After their marriage on 29 March 1797, Godwin and Wollstonecraft moved to 29 The Polygon, Somers Town. Godwin rented an apartment 20 doors away at 17 Evesham Buildings in Chalton Street as a study, so that they could both still retain their independence; they often communicated by letter.[61][62] By all accounts, theirs was a happy and stable, though brief, relationship.[63]

Birth of Mary, death

On 30 August 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter, Mary. Although the delivery seemed to go well initially, the placenta broke apart during the birth and became infected; childbed fever (post-partum infection) was a common and often fatal occurrence in the eighteenth century.[64] After several days of agony, Wollstonecraft died of septicaemia on 10 September.[65] Godwin was devastated: he wrote to his friend Thomas Holcroft, "I firmly believe there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again."[66] She was buried in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church, where her tombstone reads "Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: Born 27 April 1759: Died 10 September 1797."[67]

Posthumous, Godwin's Memoirs

In January 1798 Godwin published his Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Although Godwin felt that he was portraying his wife with love, compassion, and sincerity, many readers were shocked that he would reveal Wollstonecraft's illegitimate children, love affairs, and suicide attempts.[68] The Romantic poet Robert Southey accused him of "the want of all feeling in stripping his dead wife naked" and vicious satires such as The Unsex'd Females were published.[69] Godwin's Memoirs portrays Wollstonecraft as a woman deeply invested in feeling who was balanced by his reason and as more of a religious sceptic than her own writings suggest.[70] Godwin's views of Wollstonecraft were perpetuated throughout the nineteenth century and resulted in poems such as "Wollstonecraft and Fuseli" by British poet Robert Browning and that by William Roscoe which includes the lines:[71]

Hard was thy fate in all the scenes of life

As daughter, sister, mother, friend, and wife;

But harder still, thy fate in death we own,

Thus mourn'd by Godwin with a heart of stone.

In 1851, Wollstonecraft's remains were moved by her grandson Percy Florence Shelley to his family tomb in St Peter's Church, Bournemouth.[72]

Legacy

Wollstonecraft has what scholar Cora Kaplan labelled in 2002 a 'curious' legacy that has evolved over time: 'for an author-activist adept in many genres ... up until the last quarter-century Wollstonecraft's life has been read much more closely than her writing'.[74] After the devastating effect of Godwin's Memoirs, Wollstonecraft's reputation lay in tatters for nearly a century; she was pilloried by such writers as Maria Edgeworth, who patterned the 'freakish' Harriet Freke in Belinda (1801) after her. Other novelists such as Mary Hays, Charlotte Smith, Fanny Burney, and Jane West created similar figures, all to teach a 'moral lesson' to their readers.[75] (Hays had been a close friend, and helped nurse her in her dying days.)[76]

In contrast, there was one writer of the generation after Wollstonecraft who apparently did not share the judgmental views of her contemporaries. Jane Austen never mentioned the earlier woman by name, but several of her novels contain positive allusions to Wollstonecraft's work.[77] The American literary scholar Anne K. Mellor notes several examples. In Pride and Prejudice, Mr Wickham seems to be based upon the sort of man Wollstonecraft claimed that standing armies produce, while the sarcastic remarks of protagonist Elizabeth Bennet about 'female accomplishments' closely echo Wollstonecraft's condemnation of these activities. The balance a woman must strike between feelings and reason in Sense and Sensibility follows what Wollstonecraft recommended in her novel Mary, while the moral equivalence Austen drew in Mansfield Park between slavery and the treatment of women in society back home tracks one of Wollstonecraft's favourite arguments. In Persuasion, Austen's characterisation of Anne Eliot (as well as her late mother before her) as better qualified than her father to manage the family estate also echoes a Wollstonecraft thesis.[77]

Scholar Virginia Sapiro states that few read Wollstonecraft's works during the nineteenth century as 'her attackers implied or stated that no self-respecting woman would read her work'.[78] (Still, as Craciun points out, new editions of Rights of Woman appeared in the UK in the 1840s and in the US in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s.[79]) If readers were few, then many were inspired; one such reader was Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who read Rights of Woman at age 12 and whose poem Aurora Leigh reflected Wollstonecraft's unwavering focus on education.[80] Lucretia Mott,[81] a Quaker minister, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Americans who met in 1840 at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, discovered they both had read Wollstonecraft, and they agreed upon the need for (what became) the Seneca Falls Convention,[82] an influential women's rights meeting held in 1848. Another woman who read Wollstonecraft was George Eliot, a prolific writer of reviews, articles, novels, and translations. In 1855, she devoted an essay to the roles and rights of women, comparing Wollstonecraft and Margaret Fuller. Fuller was an American journalist, critic, and women's rights activist who, like Wollstonecraft, had travelled to the Continent and had been involved in the struggle for reform (in this case the 1849 Roman Republic)—and she had a child by a man without marrying him.[83] Wollstonecraft's children's tales were adapted by Charlotte Mary Yonge in 1870.[84]

Wollstonecraft's work was exhumed with the rise of the movement to give women a political voice. First was an attempt at rehabilitation in 1879 with the publication of Wollstonecraft's Letters to Imlay, with prefatory memoir by Charles Kegan Paul.[85] Then followed the first full-length biography,[79] which was by Elizabeth Robins Pennell; it appeared in 1884 as part of a series by the Roberts Brothers on famous women.[76] Millicent Garrett Fawcett, a suffragist and later president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, wrote the introduction to the centenary edition (i.e. 1892) of the Rights of Woman; it cleansed the memory of Wollstonecraft and claimed her as the foremother of the struggle for the vote.[86] By 1898, Wollstonecraft was the subject of a first doctoral thesis and its resulting book.[87]

With the advent of the modern feminist movement, women as politically dissimilar from each other as Virginia Woolf and Emma Goldman embraced Wollstonecraft's life story.[88] By 1929 Woolf described Wollstonecraft—her writing, arguments, and 'experiments in living'—as immortal: 'she is alive and active, she argues and experiments, we hear her voice and trace her influence even now among the living'.[89] Others, however, continued to decry Wollstonecraft's lifestyle.[90] A biography published in 1932 refers to recent reprints of her works, incorporating new research, and to a "study" in 1911, a play in 1922, and another biography in 1924.[91] Interest in her never completely died, with full-length biographies in 1937[92] and 1951.[93]

With the emergence of feminist criticism in academia in the 1960s and 1970s, Wollstonecraft's works returned to prominence. Their fortunes reflected that of the second wave of the North American feminist movement itself; for example, in the early 1970s, six major biographies of Wollstonecraft were published that presented her 'passionate life in apposition to [her] radical and rationalist agenda'.[94] The feminist artwork The Dinner Party, first exhibited in 1979, features a place setting for Wollstonecraft.[95][96]

Wollstonecraft's work has also had an effect on feminism outside academia. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a political writer and former Muslim who is critical of Islam in general and its dictates regarding women in particular, cited the Rights of Woman in her autobiography Infidel and wrote that she was 'inspired by Mary Wollstonecraft, the pioneering feminist thinker who told women they had the same ability to reason as men did and deserved the same rights'.[97] British writer Caitlin Moran, author of the best-selling How to Be a Woman, described herself as 'half Wollstonecraft' to the New Yorker.[98] She has also inspired more widely. Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, the Indian economist and philosopher who first identified the missing women of Asia, draws repeatedly on Wollstonecraft as a political philosopher in The Idea of Justice.[99]

Several plaques have been erected to honour Wollstonecraft.[100][101][102] A commemorative sculpture, A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft by Maggi Hambling,[103][104] was unveiled on 10 November 2020;[105] it was criticised for its symbolic depiction rather than a lifelike representation of Wollstonecraft,[106] [107] which commentators felt represented stereotypical notions of beauty and the diminishing of women.[108]

In November 2020, it was announced that Trinity College Dublin, whose library had previously held forty busts, all of them of men, was commissioning four new busts of women, one of whom would be Wollstonecraft.[109]

Major works

Educational works

The majority of Wollstonecraft's early productions are about education; she assembled an anthology of literary extracts "for the improvement of young women" entitled The Female Reader and she translated two children's works, Maria Geertruida van de Werken de Cambon's Young Grandison and Christian Gotthilf Salzmann's Elements of Morality. Her own writings also addressed the topic. In both her conduct book Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) and her children's book Original Stories from Real Life (1788), Wollstonecraft advocates educating children into the emerging middle-class ethos: self-discipline, honesty, frugality, and social contentment.[110] Both books also emphasise the importance of teaching children to reason, revealing Wollstonecraft's intellectual debt to the educational views of seventeenth-century philosopher John Locke.[111] However, the prominence she affords religious faith and innate feeling distinguishes her work from his and links it to the discourse of sensibility popular at the end of the eighteenth century.[112] Both texts also advocate the education of women, a controversial topic at the time and one which she would return to throughout her career, most notably in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Wollstonecraft argues that well-educated women will be good wives and mothers and ultimately contribute positively to the nation.[113]

Vindications

Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790)

Published in response to Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which was a defence of constitutional monarchy, aristocracy, and the Church of England, and an attack on Wollstonecraft's friend, the Rev. Richard Price at the Newington Green Unitarian Church, Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) attacks aristocracy and advocates republicanism. Hers was the first response in a pamphlet war that subsequently became known as the Revolution Controversy, in which Thomas Paine's Rights of Man (1792) became the rallying cry for reformers and radicals.[failed verification][114]

Wollstonecraft attacked not only monarchy and hereditary privilege but also the language that Burke used to defend and elevate it. In a famous passage in the Reflections, Burke had lamented: "I had thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her [Marie Antoinette] with insult.—But the age of chivalry is gone."[115] Most of Burke's detractors deplored what they viewed as theatrical pity for the French queen—a pity they felt was at the expense of the people. Wollstonecraft was unique in her attack on Burke's gendered language. By redefining the sublime and the beautiful, terms first established by Burke himself in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1756), she undermined his rhetoric as well as his argument. Burke had associated the beautiful with weakness and femininity and the sublime with strength and masculinity; Wollstonecraft turns these definitions against him, arguing that his theatrical tableaux turn Burke's readers—the citizens—into weak women who are swayed by show.[116] In her first unabashedly feminist critique, which Wollstonecraft scholar Claudia L. Johnson argues remains unsurpassed in its argumentative force,[117] Wollstonecraft indicts Burke's defence of an unequal society founded on the passivity of women.[need quotation to verify][118]

In her arguments for republican virtue, Wollstonecraft invokes an emerging middle-class ethos in opposition to what she views as the vice-ridden aristocratic code of manners.[119] Influenced by Enlightenment thinkers, she believed in progress and derides Burke for relying on tradition and custom. She argues for rationality, pointing out that Burke's system would lead to the continuation of slavery, simply because it had been an ancestral tradition.[120] She describes an idyllic country life in which each family can have a farm that will just suit its needs. Wollstonecraft contrasts her utopian picture of society, drawn with what she says is genuine feeling, to Burke's false feeling.[121]

The Rights of Men was Wollstonecraft's first overtly political work, as well as her first feminist work; as Johnson contends, "it seems that in the act of writing the later portions of Rights of Men she discovered the subject that would preoccupy her for the rest of her career."[122] It was this text that made her a well-known writer.[118]

Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft argues that women ought to have an education commensurate with their position in society and then proceeds to redefine that position, claiming that women are essential to the nation because they educate its children and because they could be "companions" to their husbands rather than mere wives.[123] Instead of viewing women as ornaments to society or property to be traded in marriage, Wollstonecraft maintains that they are human beings deserving of the same fundamental rights as men. Large sections of the Rights of Woman respond vitriolically to conduct book writers such as James Fordyce and John Gregory and educational philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wanted to deny women an education. (Rousseau famously argues in Émile (1762) that women should be educated for the pleasure of men.)[124]

Wollstonecraft states that currently many women are silly and superficial (she refers to them, for example, as "spaniels" and "toys"[125]), but argues that this is not because of an innate deficiency of mind but rather because men have denied them access to education. Wollstonecraft is intent on illustrating the limitations that women's deficient educations have placed on them; she writes: "Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman's sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison."[126] She implies that, without the encouragement young women receive from an early age to focus their attention on beauty and outward accomplishments, women could achieve much more.[127]

While Wollstonecraft does call for equality between the sexes in particular areas of life, such as morality, she does not explicitly state that men and women are equal.[128] What she does claim is that men and women are equal in the eyes of God. However, such claims of equality stand in contrast to her statements respecting the superiority of masculine strength and valour.[129] Wollstonecraft famously and ambiguously writes: "Let it not be concluded that I wish to invert the order of things; I have already granted, that, from the constitution of their bodies, men seem to be designed by Providence to attain a greater degree of virtue. I speak collectively of the whole sex; but I see not the shadow of a reason to conclude that their virtues should differ in respect to their nature. In fact, how can they, if virtue has only one eternal standard? I must therefore, if I reason consequently, as strenuously maintain that they have the same simple direction, as that there is a God."[130] Her ambiguous statements regarding the equality of the sexes have since made it difficult to classify Wollstonecraft as a modern feminist, particularly since the word did not come into existence until the 1890s.[131]

One of Wollstonecraft's most scathing critiques in the Rights of Woman is of false and excessive sensibility, particularly in women. She argues that women who succumb to sensibility are "blown about by every momentary gust of feeling" and because they are "the prey of their senses" they cannot think rationally.[132] In fact, she claims, they do harm not only to themselves but to the entire civilisation: these are not women who can help refine a civilisation—a popular eighteenth-century idea—but women who will destroy it. Wollstonecraft does not argue that reason and feeling should act independently of each other; rather, she believes that they should inform each other.[133]

In addition to her larger philosophical arguments, Wollstonecraft also lays out a specific educational plan. In the twelfth chapter of the Rights of Woman, "On National Education", she argues that all children should be sent to a "country day school" as well as given some education at home "to inspire a love of home and domestic pleasures." She also maintains that schooling should be co-educational, arguing that men and women, whose marriages are "the cement of society", should be "educated after the same model."[134]

Wollstonecraft addresses her text to the middle-class, which she describes as the "most natural state", and in many ways the Rights of Woman is inflected by a bourgeois view of the world.[135] It encourages modesty and industry in its readers and attacks the uselessness of the aristocracy. But Wollstonecraft is not necessarily a friend to the poor; for example, in her national plan for education, she suggests that, after the age of nine, the poor, except for those who are brilliant, should be separated from the rich and taught in another school.[136]

Novels

Both of Wollstonecraft's novels criticise what she viewed as the patriarchal institution of marriage and its deleterious effects on women. In her first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788), the eponymous heroine is forced into a loveless marriage for economic reasons; she fulfils her desire for love and affection outside marriage with two passionate romantic friendships, one with a woman and one with a man. Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798), an unfinished novel published posthumously and often considered Wollstonecraft's most radical feminist work,[137] revolves around the story of a woman imprisoned in an insane asylum by her husband; like Mary, Maria also finds fulfilment outside of marriage, in an affair with a fellow inmate and a friendship with one of her keepers. Neither of Wollstonecraft's novels depict successful marriages, although she posits such relationships in the Rights of Woman. At the end of Mary, the heroine believes she is going "to that world where there is neither marrying, nor giving in marriage",[138] presumably a positive state of affairs.[139]

Both of Wollstonecraft's novels also critique the discourse of sensibility, a moral philosophy and aesthetic that had become popular at the end of the eighteenth century. Mary is itself a novel of sensibility and Wollstonecraft attempts to use the tropes of that genre to undermine sentimentalism itself, a philosophy she believed was damaging to women because it encouraged them to rely overmuch on their emotions. In The Wrongs of Woman the heroine's indulgence on romantic fantasies fostered by novels themselves is depicted as particularly detrimental.[140]

Female friendships are central to both of Wollstonecraft's novels, but it is the friendship between Maria and Jemima, the servant charged with watching over her in the insane asylum, that is the most historically significant. This friendship, based on a sympathetic bond of motherhood, between an upper-class woman and a lower-class woman is one of the first moments in the history of feminist literature that hints at a cross-class argument, that is, that women of different economic positions have the same interests because they are women.[141]

Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796)

Wollstonecraft's Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark is a deeply personal travel narrative. The 25 letters cover a wide range of topics, from sociological reflections on Scandinavia and its peoples to philosophical questions regarding identity to musings on her relationship with Imlay (although he is not referred to by name in the text). Using the rhetoric of the sublime, Wollstonecraft explores the relationship between the self and society. Reflecting the strong influence of Rousseau, Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark shares the themes of the French philosopher's Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1782): "the search for the source of human happiness, the stoic rejection of material goods, the ecstatic embrace of nature, and the essential role of sentiment in understanding".[142] While Rousseau ultimately rejects society, however, Wollstonecraft celebrates domestic scenes and industrial progress in her text.[143]

Wollstonecraft promotes subjective experience, particularly in relation to nature, exploring the connections between the sublime and sensibility. Many of the letters describe the breathtaking scenery of Scandinavia and Wollstonecraft's desire to create an emotional connection to that natural world. In so doing, she gives greater value to the imagination than she had in previous works.[144] As in her previous writings, she champions the liberation and education of women.[145] In a change from her earlier works, however, she illustrates the detrimental effects of commerce on society, contrasting the imaginative connection to the world with a commercial and mercenary one, an attitude she associates with Imlay.[146]

Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark was Wollstonecraft's most popular book in the 1790s. It sold well and was reviewed positively by most critics. Godwin wrote "if ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book."[59] It influenced Romantic poets such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who drew on its themes and its aesthetic.[147]

작품 목록

이것은 Mary Wollstonecraft의 작품의 전체 목록입니다. 달리 명시되지 않는 한 모든 작품은 초판입니다. [148]

저자 Wollstonecraft

- 딸 교육에 대한 생각 : 삶의 더 중요한 의무에서 여성 행동에 대한 반성. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1787.

- 메리 : 소설. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1788.

- 실생활의 독창적 인 이야기 : 애정을 조절하고 진실과 선에 대한 마음을 형성하기 위해 계산 된 대화. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1788.

- 여성 독자 : 또는, 산문과 구절에서 기타 조각; 최고의 작가 중에서 선택되고 적절한 머리 아래에 배치; 젊은 여성의 개선을 위해. 크레스윅 씨, 웅변의 교사 [메리 울스턴크래프트]. 여기에는 여성 교육에 대한 힌트가 포함 된 서문 접두어가 붙어 있습니다. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1789. [149]

- 남성의 권리에 대한 옹호, 명예로운 에드먼드 버크 (Edmund Burke)에게 보내는 편지에서. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1790.

- 도덕적, 정치적 주제에 대한 엄격한 여성의 권리에 대한 증거. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1792.

- "여성의 성적 성격에 대한 지배적 인 의견, 그레고리 박사의 딸에 대한 유산에 대한 엄격함". 새로운 연례 등록 (1792) : 457-466. [여성의 권리로부터]

- 프랑스 혁명에 대한 역사적, 도덕적 견해; 그리고 그것이 유럽에서 만들어 낸 효과. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1794.

- 스웨덴, 노르웨이, 덴마크의 짧은 거주지에서 쓴 편지. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1796.

- "시와 자연의 아름다움에 대한 우리의 즐거움". 월간 잡지 (April 1797).

- 여자의 잘못, 또는 마리아. 여성의 권리에 대한 변증의 저자의 사후 작품. 에드. 윌리엄 고드윈. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1798. [사후 출판; 미완성]

- "공상의 동굴". 여성의 권리에 대한 변증의 저자의 사후 작품. 에드. 윌리엄 고드윈. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1798. [사후 출판; 1787 년에 쓰여진 단편]

- "프랑스 민족의 현재 성격에 관한 편지". 여성의 권리에 대한 변증의 저자의 사후 작품. 에드. 윌리엄 고드윈. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1798. [사후 출판; 1793 년 작성]

- "유아 관리에 관한 편지의 단편". 여성의 권리에 대한 변증의 저자의 사후 작품. 에드. 윌리엄 고드윈. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1798. [사후 출판; 미완성]

- "교훈". 여성의 권리에 대한 변증의 저자의 사후 작품. 에드. 윌리엄 고드윈. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1798. [사후 출판; 미완성]

- "힌트". 여성의 권리에 대한 변증의 저자의 사후 작품. 에드. 윌리엄 고드윈. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1798. [사후에 출판; 여성의 권리의 두 번째 권에 대한 메모, 결코 쓰여지지 않음]

- 분석 검토에 대한 기여 (1788-1797) [익명으로 출판]

번역: 울스턴크래프트

- 네커, 자크. 종교적 의견의 중요성. 트랜스. 메리 울스턴크래프트. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1788.

- de Cambon, Maria Geertruida van de Werken. 젊은 그랜디슨. 젊은이들이 친구들에게 보내는 일련의 편지. 트랜스. 메리 울스턴크래프트. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1790.

- 잘츠만, 크리스티안 고틸프. 도덕성의 요소, 어린이 사용; 부모에 대한 소개 연설. 트랜스. 메리 울스턴크래프트. 런던 : 조셉 존슨, 1790.

또한 보십시오

- 90481 울스턴크래프트, 소행성

- 고드윈-셸리 가계도

- 메리 울스턴크래프트의 타임라인

- 에드워드 울스턴크래프트(Edward Wollstonecraft), 그녀의 조카, 초기 식민지 호주에서 중요한 인물

노트

- ^ .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit;word-wrap:break-word}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"\""""""}.mw-parser-output .citation:target{background-color:rgba(0,127,255,0.133)}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-free a,.mw-parser-output .{color:#d33}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#3a3;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right{padding-right:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .citation .mw-selflink{font-weight:inherit}"Mary Wollstonecraft". 옥스포드 학습자의 사전. 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 2020년 11월 12일에 확인함.

- ^ 프랭클린, xiv.

- ^ 로시, 25세.

- ^ 토말린, 9, 17, 24, 27; 선스타인, 11쪽.

- ^ 토드, 11; 토말린, 19; 와들, 6; 선스타인, 16세.

- ^ 토드, 45~57쪽; 토말린, 34~43쪽; 와들, 27~30쪽; 선스타인, 80~91쪽.

- ^ 토드, 16에서 인용.

- ^ 예를 들어, 토드, 72~75쪽; 토말린, 18~21쪽; 선스타인, 22~33쪽.

- ^ 토드, 22~24쪽; 토말린, 25~27쪽; 와들, 10~11쪽; 선스타인, 39~42쪽.

- ^ 와들, 12~18쪽; 선스타인 51~57세.

- ^ 와들, 20; 선스타인, 73~76쪽.

- ^ 토드, 62; 와들, 30~32쪽; 선스타인, 92~102쪽.

- ^ 토드, 68~69쪽; 토말린, 52ff; 와들, 43~45쪽; 선스타인, 103~106쪽.

- ^ 토말린, 54~57쪽.

- ^ 와들, 2장, 마리아의 자서전적 요소들을 보라. 선스타인, 7장 참조.

- ^ 예를 들어, 토드, 106~107쪽; 토말린, 66, 79~80; 선스타인, 127~128쪽.

- ^ 토드, 116쪽.

- ^ 토말린, 64~88쪽; 와들, 60ff; 선스타인, 160~161쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, 수집된 편지들, 139쪽; 또한 선스타인, 154쪽 참조.

- ^ 토드, 123; 토말린, 91~92쪽; 와들, 80~82쪽; 선스타인, 151~155쪽.

- ^ 토드, 134–135.

- ^ 토말린, 89~109쪽; 와들, 92~94쪽, 128쪽; 선스타인, 171~175쪽.

- ^ "메리 울스턴크래프트 블루 플라크 공개". 런던 SE1. 2020년 8월 6일에 확인함.

- ^ 토드, 153에서 인용.

- ^ 토드, 197–198; 토말린 151~152; 와들, 76~77, 171~173쪽; 선스타인, 220~222쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 Furniss 60.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Furniss 61.

- ^ 토말린, 144~155쪽; 와들, 115ff; 선스타인, 192~202쪽.

- ^ Furniss 63.

- ^ 퍼니스 64.

- ^ 토드, 214~215쪽; 토말린, 156~182쪽; 와들, 179~184쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 Furniss 65.

- ^ 퍼거스 웬런 (2014). 하나님을 자극하는 민주당 원: 아치볼드 해밀턴 로완의 놀라운 삶. 스틸오르간, 더블린: 뉴 아일랜드 북스. 151쪽. ISBN 978-1-84840-460-1.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Furniss 68.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Furniss 66.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Furniss 67.

- ^ 토드, 232–236; 토말린, 185~186쪽; 와들, 185~188쪽; 선스타인, 235~245쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Gordon 215.

- ↑ 가 나 Gordon 214–215.

- ^ 고든 215, 224.

- ^ 세인트 클레어, 160; 푸르니스, 67; 선스타인, 262~263쪽; 와들, 192~193쪽.

- ^ 토말린, 218; 와들, 202–203; 선스타인, 256~257쪽.

- ^ Wardle, 202에서 인용.

- ^ 토말린, 211~219쪽; 와들, 206~214쪽; 선스타인, 254~255쪽.

- ^ 토드, 제25장; 토말린, 220~231쪽; 와들, 215ff; 선스타인, 262ff.

- ^ 푸르니스 67–68.

- ^ 고든 243.

- ^ 토말린, 225쪽.

- ^ 푸르니스 68–69.

- ^ Furniss 72.

- ↑ 가 나 다 Callender 384.

- ^ 아돌푸스, 존 (1799). 프랑스 혁명의 전기 회고록. 권. 1. 런던 : T. Cadell, Jun. 및 W. Davies, Strand에서. 5, 6쪽.

- ^ 토드, 286~287쪽; 와들, 225쪽.

- ^ 토말린, 225~231쪽; 와들, 226~244쪽; 선스타인, 277~290쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, 수집된 편지들, 326~327쪽.

- ^ 토드, 355~356쪽; 토말린, 232~236쪽; 와들, 245~246쪽.

- ^ 토드, 357쪽.

- ^ 세인트 클레어, 164~169쪽; 토말린, 245~270쪽; 와들, 268ff; 선스타인, 314~320쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 Godwin, 95.

- ^ 성 클레어, 172~174쪽; 토말린, 271~273쪽; 선스타인, 330~335쪽.

- ^ 칼 포르츠하이머 도서관 (1961). "메리 울스턴크래프트의 죽음". 카메론에서, 케네스 닐; 레이먼, 도널드 H. (eds.). 셸리와 그의 서클, 1773-1822, 볼륨 1. 하버드 대학 출판부. 185쪽.

- ^ Sunstein은 독자가 Wollstonecraft와 Godwin의 대화 (321ff)를 따라갈 수 있도록이 편지 중 몇 가지를 인쇄했습니다.

- ^ 세인트 클레어, 173; 와들, 286~292쪽; 선스타인, 335~340쪽.

- ^ 고든, 356쪽.

- ^ 토드, 450~456쪽; 토말린, 275~283쪽; 와들, 302~306쪽; 선스타인, 342~347쪽.

- ^ C. Kegan Paul, William Godwin : His Friends and Contemporaries, London : Henry S. King and Co. (1876)에서 인용. 2007년 3월 11일에 확인함.

- ^ 토드, 457쪽.

- ^ 세인트 클레어, 182~88쪽; 토말린, 289~297쪽; 선스타인, 349~351쪽; 사피로, 272쪽.

- ^ 로버트 수니 - 윌리엄 테일러, 1804년 7월 1일. 노리치의 윌리엄 테일러의 삶과 저술에 대한 회고록. 에드 J.W. 강도. 2권. 런던: 존 머레이 (1824) 1:504.

- ^ 사피로, 273~274쪽.

- ^ 사피로, 273에서 인용.

- ^ 고든, 446쪽.

- ^ 팀, 런던 SE1 웹 사이트. "메리 울스턴크래프트 블루 플라크 공개". 런던 SE1. 2018년 5월 6일에 확인함.

- ^ 카플란, "울스턴크래프트의 리셉션", 247쪽.

- ^ 파브렛, 131~132쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 Pennell, Elizabeth Robins. 메리 울스턴크래프트의 생애 (보스턴: 로버츠 브라더스, 1884년), 351쪽. 전체 텍스트.

- ↑ 가 나 Mellor 156.

- ^ 사피로, 274쪽.

- ↑ 가 나 A Routledge literary sourcebook on Mary Wollstonecraft's A vindication of the rights of woman. Adriana Craciun, 2002, p. 36.

- ^ 고든, 449쪽.

- ^ 사피로, 276~277쪽.

- ^ Lasser & Robertson (2013). Antebellum Women: Private, Public, Partisan. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 46–47.

- ^ Dickenson, Donna. Margaret Fuller: Writing a Woman's Life (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993). ISBN 978-0-312-09145-3, 45–46.

- ^ 헤윈스, C.M. (캐롤라인 엠 헤윈스, 1846-1926) "어린이 책의 역사", 대서양 월간지. 1888년 1월.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, 메리. 임레이에게 보내는 편지, C. Kegan Paul의 예비 회고록. 런던 : C. 케건 폴, 1879. 전체 텍스트.

- ^ 고든, 521쪽.

- ^ James, H. R. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Sketch. 옥스포드 대학 출판부, 1932. 부록 B: 메리 울스턴크래프트에 관한 책. Miss Emma Rauschenbusch-Clough, "Berne University에서 박사 학위 논문", Longmans.

- ^ 울프, 버지니아. "The Four Figures Archived 3 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine" (2004년 6월 4일 업데이트). 2007년 3월 11일에 확인함.

- ^ 카플란, 코라. "Mary Wollstonecraft의 리셉션과 유산". 메리 울스턴크래프트의 케임브리지 컴패니언. 에드. 클라우디아 L. 존슨. 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. 캠브리지 컬렉션 온라인. 케임브리지 대학 출판부. 2010년 9월 21일 doi:10.1017/CCOL0521783437.014

- ^ "참정권 원인은 남자 클럽을 침범한다". 뉴욕 타임즈. 1910년 5월 25일.

- ^ James, H. R. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Sketch. 옥스포드 대학 출판부 1932. 머리말.

- ^ Preedy, George R., Marjorie Bowen의 가명. 빛나는 여인 : 메리 울스턴크래프트 고드윈. 콜린스, 런던, 1937년.

- ^ Wardle, Ralph M. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Critical Biography. 캔자스 대학. 리차즈 출판사, 세인트 제임스 광장, 1951.

- ^ 카플란, "울스턴크래프트의 리셉션", 254쪽; 사피로, 278~279쪽.

- ^ 장소 설정. 브루클린 박물관. 2015년 8월 6일에 확인함.

- ^ "투어와 홈". 브루클린 박물관. 1979년 3월 14일. 2015년 8월 12일에 확인함.

- ^ 히르시 알리, 아야안. 인피델. 뉴욕 : 자유 언론 (2007), 295.

- ^ 샐리 에리코의 인터뷰. "Half Wollstonecraft, Half LOLcats: Talking with Caitlin Moran", in The New Yorker, 15 November 2012. [1]

- ^ "BBC 라디오 4 시리즈 메리에게 보내는 편지 : 에피소드 2". BBC. 2014년 10월 21일에 확인함.

- ^ "메리 울스턴크래프트 브라운 플라크". 플라크를 엽니다. 2018년 4월 27일에 확인함.

- ^ "자치구의 푸른 플라크". Williamslynch.co.uk. 17 행진 2017. 2018년 6월 24일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2018년 4월 27일에 확인함.

- ^ "Mary Wollstonecraft는 Newington Green Primary에서 녹색 상패를 얻습니다 ... 동상이 다음에 있을까요?". 이슬링턴 트리뷴. Archive.islingtontribune.com. 2011년 3월 11일. 2018년 4월 28일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2018년 4월 27일에 확인함.

- ^ Slawson, Nicloa (16 May 2018). "Maggi Hambling은 Mary Wollstonecraft 동상을 만들기 위해 골랐습니다." 가디언.

- ^ Hedges, Frances (2019년 2월 22일). "Maggi Hambling은 페미니스트 아이콘 Mary Wollstonecraft에게 경의를 표합니다." 타운 & 컨트리.

- ^ 록하트, 알라스테어 (2020년 10월 26일). "Wollstonecraft to make Newington Green return". 《Wollstonecraft》. 이슬링턴 지금.

- ^ "메리 울스턴크래프트 동상: '페미니즘의 어머니' 조각품이 반발을 불러일으킨다". BBC 뉴스. 2020년 11월 10일.

- ^ "페미니스트 아이콘 메리 울스턴크래프트를 기리는 누드 동상이 비판을 촉발시킨다". NBC 뉴스. 2020년 11월 11일에 확인함.

- ^ Cosslett, Rhiannon Lucy (2020년 11월 10일). "왜 내가 메리 울스턴크래프트 동상을 싫어하는가: 한 남자가 그의 술렁이로 '명예롭게' 될 것인가?". 가디언. ISSN 0261-3077. 2020년 11월 11일에 확인함.

- ^ "트리니티 롱 룸의 "남자 전용"이미지를 끝내기위한 네 개의 새로운 동상". www.irishtimes.com. 2020년 11월 29일에 확인함.

- ^ 존스, "충고의 문학", 122~126쪽; 켈리, 58~59세.

- ^ 리처드슨, 24~27쪽; 마이어스, "흠 잡을 데 없는 통치", 38쪽.

- ^ 존스, "충고의 문학", 124~129쪽; 리처드슨, 24~27쪽.

- ^ 리처드슨, 25~27쪽; 존스, "조언의 문학", 124쪽; 마이어스, "흠 잡을 데 없는 통치", 37~39쪽.

- ^ "시민권". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. 2021년 3월 23일에 확인함.

- ^ Qtd. 버틀러, 44쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, 변증, 45쪽; 존슨, 26; 사피로, 121~122쪽; 켈리, 90, 97–98.

- ^ 존슨, 27; 또한 토드, 165쪽 참조.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman". 《Mary Wollstonecraft》. 영국 도서관. 2021년 3월 23일에 확인함.

- ^ 사피로, 83; 켈리, 94~95쪽; 토드, 164쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, Vindications, 44쪽.

- ^ 존스, "정치적 전통", 44~46쪽; 사피로, 216쪽.

- ^ 존슨, 29세.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, Vindications, 192쪽.

- ^ 켈리, 123, 126; 테일러, 14~15쪽; 사피로, 27~28, 13~31, 243~244쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, 변증, 144쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, Vindications, 157쪽.

- ^ 켈리, 124~126쪽; 테일러, 14~15쪽.

- ^ 예를 들어 Wollstonecraft, Vindications, 126, 146 참조.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, Vindications, 110쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, Vindications, 135쪽.

- ^ 페미니스트와 페미니즘이라는 단어는 1890년대에 만들어졌다. 2007년 9월 17일에 확인함; 테일러, 12, 55~57, 105~106, 118~120; 사피로, 257~259쪽.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, Vindications, 177쪽.

- ^ 존스, 46세.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, 변증, 제12장; 또한 켈리, 124~125, 133~134; 사피로, 237ff.

- ^ 켈리, 128ff; 테일러, 167~168쪽; 사피로, 27세.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, Vindications, 311; 또한 테일러, 159~161쪽; 사피로, 91~92쪽.

- ^ 테일러, 제9장.

- ^ 울스턴크래프트, 메리, 68쪽.

- ^ 푸비, 100–101; 테일러, 232–233.

- ^ 존슨, 60, 65~66; 켈리, 44; 푸비, 89; 테일러, 135; 토드, 여성의 우정, 210-211쪽.

- ^ 토드, 여자 우정, 208, 221~222; 존슨, 67~68쪽; 테일러, 233, 243~244; 사피로, 155쪽.

- ^ 파브렛, 104; 사피로, 286~287쪽.

- ^ 파브렛, 105~106쪽.

- ^ 마이어스, "울스턴크래프트의 편지", 167, 180쪽; 푸비, 83–84, 106; 켈리, 189~190쪽.

- ^ 마이어스, "울스턴크래프트의 편지", 174쪽; 파브렛, 96, 120, 127.

- ^ 파브렛, 119ff; 푸비, 93; 마이어스, "울스턴크래프트의 편지", 177쪽; 켈리, 179~181쪽.

- ^ 토드, 367; 카플란, "메리 울스턴크래프트의 리셉션", 262쪽; 사피로, 35; 파브렛, 128쪽.

- ^ 사피로, 341ff.

- ^ 여성 독자는 펜 이름으로 출판되었지만 실제로 Wollstonecraft가 저술했습니다.

서지학

초등회 작품

- 버틀러, 마릴린, 에드. 버크, 페인, 고드윈, 혁명 논쟁. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-28656-5.

- 울스턴크래프트, 메리. 메리 울스턴크래프트의 수집 편지. 에드. 자넷 토드. 뉴욕 : 컬럼비아 대학 출판부, 2003. ISBN 978-0-231-13142-1.

- 울스턴크래프트, 메리. 메리 울스턴크래프트의 완성된 작품들. 에드. 자넷 토드와 마릴린 버틀러. 7권. 런던: 윌리엄 피커링, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8147-9225-4.

- 울스턴크래프트, 메리. 변증: 남성의 권리와 여성의 권리. Eds. D.L. Macdonald와 Kathleen Scherf. 토론토: 브로드뷰 프레스, 1997. ISBN 978-1-55111-088-2.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary (2005), "사회에서 확립 된 부자연스러운 구별에서 발생하는 해로운 영향에 관한", Cudd, Ann E.; 안드레아센, 로빈 O. (eds.), 페미니스트 이론 : 철학적 선집, 옥스포드, 영국; 말든, 매사추세츠: 블랙웰 출판, pp. 11-16, ISBN 978-1-4051-1661-9.

전기

- 프랭클린, 캐롤라인. 메리 울스턴크래프트: 문학적 삶. 스프링어, 2004. ISBN 978-0-230-51005-0

- 플렉스너, 엘레노어. 메리 울스턴크래프트: 전기. 뉴욕 : 겁쟁이, McCann and Geoghegan, 1972. ISBN 978-0-698-10447-1.

- 고드윈, 윌리엄. 여성의 권리에 대한 변증의 저자의 회고록. 1798. Eds. Pamela Clemit과 Gina Luria Walker. Peterborough: Broadview Press Ltd., 2001. ISBN 978-1-55111-259-6.

- 고든, 샬럿. 낭만적 인 무법자 : 메리 울스턴크래프트와 메리 셸리의 특별한 삶. 영국 : 랜덤 하우스, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8129-9651-7. 책의 웹 사이트.

- 고든, 린달. Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. 영국: 비라고, 2005. ISBN 978-1-84408-141-7.

- 건초, 메리. "메리 울스턴크래프트의 회고록". 연례 Necrology (1797-98) : 411-460.

- 제이콥스, 다이앤. 그녀 자신의 여자 : 메리 울스턴크래프트의 삶. 미국: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 978-0-349-11461-3.

- 폴, 찰스 케건. 임레이에게 보내는 편지, C. Kegan Paul의 예비 회고록. 런던 : C. 케건 폴, 1879. 전체 텍스트

- 페넬, 엘리자베스 로빈스. 메리 울스턴크래프트의 생애 (보스턴: 로버츠 브라더스, 1884). 전체 텍스트

- 세인트 클레어, 윌리엄. Godwins와 Shelleys : 가족의 전기. 뉴욕 : W.W. Norton and Co., 1989. ISBN 978-0-8018-4233-7.

- 선스타인, 에밀리. 다른 얼굴 : 메리 울스턴크래프트의 삶. 보스턴: 리틀, 브라운 앤 주식회사, 1975. ISBN 978-0-06-014201-8.

- 토드, 자넷. 메리 울스턴크래프트: 혁명적인 삶. 런던 : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000. ISBN 978-0-231-12184-2.

- 토말린, 클레어. 메리 울스턴크래프트의 삶과 죽음. 개정판 ed. 1974. 뉴욕 : 펭귄, 1992. ISBN 978-0-14-016761-0.

- Wardle, Ralph M. Mary Wollstonecraft: A Critical Biography. 링컨 : 네브래스카 대학 출판부, 1951.

다른 보조 작품

- Callender, Michelle "정치 변화의 웅장한 극장": 마리 앙투아네트, 공화국, 그리고 메리 울스턴크래프트의 프랑스 혁명에 대한 역사적, 도덕적 견해"pp. 375-392 from European Romantic Review, Volume 11, Issue 4, Fall 2000.

- Conger, Syndy McMillen. Mary Wollstonecraft와 감성의 언어. 러더퍼드: 페어리 디킨슨 대학 출판부, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8386-3553-7.

- 데트레, 진. 가장 특별한 쌍 : 메리 울스턴크래프트와 윌리엄 고드윈, 가든 시티 : 더블데이, 1975

- Falco, Maria J., ed. Mary Wollstonecraft의 페미니스트 해석. 대학 공원 : 펜 스테이트 프레스, 1996. ISBN 978-0-271-01493-7.

- 파브렛, 메리. 낭만적 인 서신 : 여성, 정치 및 편지의 허구. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 1993. ISBN 978-0-521-41096-0.

- 푸르니스, 톰. "Mary Wollstonecraft의 프랑스 혁명". 메리 울스턴크래프트의 케임브리지 컴패니언. 에드. 클라우디아 L. 존슨. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. 59~81쪽. ISBN 978-0-521-78952-3

- 할데니우스, 레나. Mary Wollstonecraft와 페미니스트 공화주의 : 독립, 권리 및 자유의 경험, 런던 : Pickering & Chatto, 2015. ISBN 978-1-84893-536-5.

- 홈즈, 리처드. "1968 : 혁명", 발자취 : 낭만주의 전기 작가의 모험. Hodder & Stoughton, 1985. ISBN 978-0-00-720453-3.

- Janes, R.M. "Mary Wollstonecraft의 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman"의 리셉션에서. 아이디어 역사 저널 39 (1978) : 293-302.

- 존슨, 클라우디아 L. 모호한 존재 : 1790 년대의 정치, 성별 및 감상성. 시카고 : 시카고 대학 출판부, 1995. ISBN 978-0-226-40184-3.

- 존스, 크리스. "Mary Wollstonecraft의 Vindications and Their Political Tradition". 《Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindications and Their Political Tradition》. 메리 울스턴크래프트의 케임브리지 컴패니언. 에드. 클라우디아 L. 존슨. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-78952-3.

- 존스, 비비안. "Mary Wollstonecraft와 조언과 가르침의 문학". 메리 울스턴크래프트의 케임브리지 컴패니언. 에드. 클라우디아 존슨. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-78952-3.

- 카플란, 코라. "Mary Wollstonecraft의 리셉션과 유산". 메리 울스턴크래프트 에드 클라우디아 L. 존슨의 케임브리지 동반자. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-78952-3.

- —. "판도라의 상자 : 사회주의 페미니스트 비판의 주관성, 계급 및 섹슈얼리티". 바다 변화 : 문화와 페미니즘에 관한 수필. 런던 : 베르소, 1986. ISBN 978-0-86091-151-7.

- —. "와일드 나이트 : 즐거움 / 섹슈얼리티 / 페미니즘". 바다 변화 : 문화와 페미니즘에 관한 수필. 런던 : 베르소, 1986. ISBN 978-0-86091-151-7.

- 켈리, 게리. 혁명적 페미니즘: 메리 울스턴크래프트의 마음과 경력. 뉴욕 : 세인트 마틴스, 1992. ISBN 978-0-312-12904-0.

- 맥엘로이, 웬디 (2008). "울스턴크래프트, 메리 (1759-1797)". Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). 자유의지주의의 백과사전. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Cato Institute. 545~546쪽. doi : 10.4135 / 9781412965811.n331. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Mellor, Anne K. "Mary Wollstonecraft의 A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and the Women Writers of Her Day." The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft, 편집: Claudia L. Johnson, 141–159쪽. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. 도이 : 10.1017 / CCOL0521783437.009.

- 마이어스, 미치. "흠 잡을 데없는 통치, 합리적인 댐, 도덕적 어머니 : 메리 울스턴 크래프트와 조지아 어린이 책의 여성 전통". 아동 문학 14 (1986):31–59.

- —. "감성과 '이성의 산책' : 문화 비평으로서의 메리 울스턴크래프트의 문학적 리뷰". 변형의 감성 : 아우구스탄에서 낭만주의에 이르기까지 감정에 대한 창조적 저항. 에드. 신디 맥밀렌 콘저. 러더퍼드: 페어리 디킨슨 대학 출판부, 1990. ISBN 978-0-8386-3352-6.

- —. "울스턴크래프트의 편지 작성... 스웨덴에서 : 낭만주의 자서전을 향해". 열여덟 세기 문화 연구 8 (1979) : 165-185.

- Orr, Clarissa Campbell, ed. Wollstonecraft의 딸 : 영국과 프랑스의 여성성, 1780-1920. 맨체스터 : 맨체스터 대학 출판부 ND, 1996.

- 푸비, 메리. 적절한 숙녀와 여성 작가 : 메리 울스턴크래프트, 메리 셸리, 제인 오스틴의 작품에서 스타일로서의 이데올로기. 시카고 : 시카고 대학 출판부, 1984. ISBN 978-0-226-67528-2.

- 리처드슨, 앨런. "Mary Wollstonecraft on education". 《Mary Wollstonecraft on Education》. 메리 울스턴크래프트의 케임브리지 컴패니언. 에드. 클라우디아 존슨. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-78952-3.

- 로시, 앨리스. 페미니스트 논문 : 아담스에서 드 보부아르까지. 북동부, 1988년.

- 사피로, 버지니아. 정치적 미덕의 증거 : 메리 울스턴크래프트의 정치 이론. 시카고 : 시카고 대학 출판부, 1992. ISBN 978-0-226-73491-0.

- 테일러, 바바라. 메리 울스턴크래프트와 페미니스트의 상상력. 케임브리지 : 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-66144-7.

- 토드, 자넷. 문학에서 여성의 우정. 뉴욕 : 컬럼비아 대학 출판부, 1980. ISBN 978-0-231-04562-9

외부 링크

- Mary Wollstonecraft on In Our Time at the BBC

- Mary Wollstonecraft의 작품 in eBook in eBook at Standard Ebooks

- 프로젝트 구텐베르크에서 Mary Wollstonecraft의 작품

- Mary Wollstonecraft에 의해 또는 인터넷 아카이브에서 작품

- LibriVox의 Mary Wollstonecraft의 작품 (공개 도메인 오디오 북)

- 오픈 라이브러리에서 작동

- Mary Wollstonecraft: BBC History의 Janet Todd의 '투기적이고 반대하는 정신'

- 토마셀리, 실바나. "메리 울스턴크래프트". 잘타에서, 에드워드 N. (ed.). 스탠포드 철학 백과사전.

- Mary Wollstonecraft 원고 자료, 1773-1797, Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle, 뉴욕 공립 도서관

- "Mary Wollstonecraft와 관련된 아카이브 자료". 영국 국립 기록 보관소.

- 런던 국립 초상화 갤러리에서 메리 울스턴크래프트의 초상화

- Bodleian Library, University of Oxford Archived 7 August 2018 at Wayback Machine

- 1759 출생

- 1797명 사망

- 스피탈필드의 사람들

- 런던 소머스 타운에서 온 사람들

- 18세기 영국 소설가

- 18세기 영국 철학자

- 18세기 영국 여성 작가

- 18세기 수필가

- 세인트 판크라스 올드 교회의 매장

- 출산 중 사망

- 패혈증으로 인한 사망

- 영어 통치

- 런던의 학교 교사

- 교육 작가

- 18세기 영국 역사가

- 영국 여성 소설가

- 영어 여행 작가

- 영어 유니타리안

- 영국 페미니스트

- 영어 수필가

- 영국 철학자

- 영국 여성 철학자

- 영국 페미니스트 작가

- 계몽주의 철학자

- 페미니스트 철학자

- 페미니스트 이론가

- 프랑스어-영어 번역가

- 독일어-영어 번역가

- 고드윈 가족

- 프랑스 혁명의 역사가들

- 영국 여성 수필가

- 영국 여성 여행 작가

- 영국 여성 역사가

- 고딕 소설의 작가

- 영어 학교 및 대학 설립자

- 영어 교육 이론가

- 영국 공화주의자

- 교육 철학자