우주론(고대 그리스어κόσμος(kósmos)'세계' 및 -λογία(-logía)'연구'에서 유래)는 우주의 본질을 다루는물리학및 형이상학의 한 분야입니다. 우주론이라는 용어는 1656년토마스 블런트의 《Glossographia》에서 영어로 처음 사용되었고,[2], 1731년독일 철학자크리스티안 볼프(Christian Wolff)가 라틴어로 채택한 우주론(Cosmologia Generalis)에서 사용되었다. [3]종교적또는 신화적 우주론은 신화적, 종교적,밀교적 문학과창조 신화와종말론의 전통에 기초한 신념의 집합체입니다. 천문학에서 그것은우주의 연대기에 대한 연구와 관련이 있습니다.

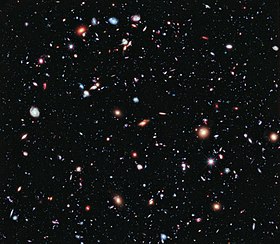

물리적 우주론은관측 가능한 우주의 기원, 대규모 구조와 역학, 그리고 이러한 영역을 지배하는과학 법칙을 포함하여우주의 궁극적인 운명에 대한 연구입니다. [4] 천문학자 및물리학 자와 같은 과학자뿐만 아니라형이상학자,물리학 철학자,공간과 시간 철학자와 같은철학자에 의해 조사됩니다. 철학과 이러한 공유 범위 때문에, 물리적 우주론의 이론은 과학적 명제와 비과학적명제를 모두 포함할 수 있으며,검증할 수 없는 가정에 의존할 수 있다. 물리적 우주론은 우주 전체와 관련된 천문학의 하위 분야입니다. 현대 물리적 우주론은관측 천문학과입자 물리학을 결합하려는빅뱅이론에 의해 지배됩니다. [5][6]보다 구체적으로,람다-CDM모델로 알려진 암흑물질과암흑 에너지를 가진 빅뱅의 표준 매개 변수화.

이론 천체 물리학자데이비드 N. 스퍼겔(David N. Spergel)은빛의 속도의 유한한 특성으로 인해 "우주를 바라볼 때 시간을 거슬러 올라가기" 때문에 우주론을 "역사 과학"으로 묘사했습니다. [7]

목차

분야편집하다

물리학과천체 물리학은 과학적 관찰과 실험을 통해 우주에 대한 이해를 형성하는 데 중심적인 역할을 했습니다. 물리적 우주론은 전체 우주에 대한 분석에서 수학과 관찰을 통해 형성되었습니다. 우주는 일반적으로빅뱅과 함께 시작되어 거의 즉각적으로 우주 팽창, 우주가13.799± 0.021억년 전에 출현한 것으로 생각되는공간의 팽창이 뒤따랐습니다. [8]우주론은 우주의 기원을 연구하고 우주론은 우주의 특징을 매핑합니다.

디드로의백과사전에서 우주론은 비뇨기학(하늘의 과학), 공기학(공기의 과학), 지질학(대륙의 과학), 수문학(물의 과학)으로 나뉩니다. [9]

형이상학 적 우주론은 또한 다른 모든 개체와의 관계에서 우주에 인간을 배치하는 것으로 묘사되었습니다. 이것은마르쿠스 아우렐리우스 (Marcus Aurelius)의 관찰에 의해 예시됩니다 : "세상이 무엇인지 모르는 사람은 자신이 어디에 있는지 모르고, 세상이 어떤 목적으로 존재하는지 모르는 사람은 자신이 누구인지, 세상이 무엇인지 모른다." [10]

발견편집하다

물리적 우주론편집하다

물리적 우주론은 우주의 물리적 기원과 진화에 대한 연구를 다루는 물리학 및 천체 물리학의 한 분야입니다. 또한 우주의 본질에 대한 대규모 연구도 포함됩니다. 가장 초기의 형태로, 그것은 현재 "천체 역학",즉 하늘에 대한 연구로 알려진 것입니다. 그리스 철학자사모스의 아리스다르코스, 아리스토텔레스,프톨레마이오스는서로 다른 우주론을 제안했습니다. 지구 중심 프톨레마이오스 시스템은니콜라우스 코페르니쿠스와이후 요하네스 케플러와 갈릴레오 갈릴레이가태양 중심시스템을 제안한 16 세기까지 지배적 인 이론이었습니다. 이것은 물리적 우주론에서인식 론적 파열의 가장 유명한 예 중 하나입니다.

1687년에 출판된 아이작 뉴턴의프린키피아 매스매티카(Principia Mathematica)는만유인력의 법칙에 대한 최초의 설명이었습니다. 그것은케플러의 법칙에 대한 물리적 메커니즘을 제공했으며 행성 간의 중력 상호 작용으로 인한 이전 시스템의 이상을 해결할 수있었습니다. 뉴턴의 우주론과 그 이전의 우주론 사이의 근본적인 차이점은 지구상의 천체가 모든 천체와 동일한물리 법칙을 따른다는코페르니쿠스적 원리였습니다. 이것은 물리적 우주론에서 중요한 철학적 진보였습니다.

현대 과학 우주론은 일반적으로 1917년알버트 아인슈타인이 "일반 상대성 이론의 우주론적 고찰"[11]이라는 논문에서일반 상대성 이론의 최종 수정을 발표하면서 시작된 것으로 간주됩니다(이 논문은제1차 세계 대전이 끝날 때까지 독일 이외의 지역에서 널리 사용되지 않았지만). 일반 상대성 이론은빌렘 드 시터, 칼 슈바르츠차일드,아서 에딩턴과 같은우주론자들이 천문학적 파급 효과를 탐구하도록 자극하여천문학자들이매우 먼 물체를 연구하는 능력을 향상시켰습니다. 물리학자들은 우주가 정적이고 변하지 않는다는 가정을 바꾸기 시작했습니다. 1922 년알렉산더 프리드만 (Alexander Friedmann)은 움직이는 물질을 포함하는 팽창하는 우주에 대한 아이디어를 소개했습니다.

우주론에 대한 이러한 역동적인 접근과 병행하여, 우주의 구조에 대한 오랜 논쟁 중 하나는대논쟁(1917-1922)으로 절정에 이르렀고,히버 커티스(Heber Curtis)와에른스트 외픽(Ernst Öpik)과 같은 초기 우주론자들은 망원경에서 볼 수 있는 일부성운이 우리 은하와 멀리 떨어져 있는 별개의 은하라고 결정했습니다. [12] 히버 커티스(Heber Curtis)는 나선 성운이 그 자체로 섬 우주로서 항성계라는 생각을 주장한 반면, 윌슨 산의 천문학자할로우 섀플리(Harlow Shapley)는은하수항성계로만 구성된 우주 모델을 옹호했습니다. 이러한 생각의 차이는 1920년 4월 26일워싱턴 D.C.에서 열린 미국 국립 과학 아카데미회의에서대토론회가 조직되면서 절정에 이르렀습니다. 논쟁은에드윈 허블 (Edwin Hubble)이 1923 년과 1924 년에안드로메다 은하에서세 페이드 변수를발견했을 때 해결되었습니다. [13][14]그들의 거리는 은하수의 가장자리를 훨씬 넘어 나선형 성운을 형성했습니다.

우주의 후속 모델링은 아인슈타인이 1917년 논문에서 소개한 우주상수가 그 가치에 따라팽창하는 우주를 초래할 수 있는 가능성을 탐구했습니다. 따라서빅뱅모델은 1927년벨기에신부Georges Lemaître에 의해 제안되었으며[15], 이후 1929년에드윈 허블의적색편이발견[16]과 1964년Arno Penzias와Robert Woodrow Wilson의우주 마이크로파 배경 복사발견에 의해 확증되었습니다. [17] 이러한 발견은 많은대체 우주론 중 일부를 배제하는 첫 번째 단계였습니다.

1990년경부터 관측 우주론의 몇 가지 극적인 발전으로우주론은 주로 사변적인 과학에서 이론과 관찰이 정확히 일치하는 예측 과학으로 변모했습니다. 이러한 발전에는COBE의 마이크로파 배경 관측,[18]WMAP[19] 및플랑크위성,[20]2dfGRS[21] 및SDSS를 포함한 대규모 새로운 은하적색편이 조사,[22]먼초신성및중력 렌즈 관측이 포함됩니다. 이러한 관측은우주 팽창이론, 수정된빅뱅이론 및람다-CDM모델로 알려진 특정 버전의 예측과 일치했습니다. 이로 인해 많은 사람들이 현대를 "우주론의 황금기"라고 불렀습니다. [23]

2014 년 3 월 17 일,천체 물리학 센터의 천문학 자들은 | Harvard & Smithsonian은중력파의 탐지를 발표하여인플레이션과빅뱅에 대한 강력한 증거를 제공했습니다. [24][25][26]그러나 2014년 6월 19일,우주 인플레이션결과를 확인하는 데 대한 신뢰도가 낮아졌다고 보고되었습니다. [27][28][29]

2014 년 12 월 1 일 이탈리아 페라라에서 열린플랑크 2014회의에서 천문학 자들은우주의나이가 138 억 년이며 4.9 % 원자 물질, 26.6 % 암흑 물질 및 68.5 % 암흑 에너지로 구성되어 있다고보고했습니다. [30]

종교적 또는 신화 적 우주론편집하다

종교적또는 신화적 우주론은신화적, 종교적,밀교문학과창조와종말론의 전통에 기초한 신념의 몸입니다.

철학적 우주론편집하다

우주론은 세계를 공간, 시간 및 모든 현상의 총체로 다룹니다. 역사적으로, 그것은 상당히 넓은 범위를 가지고 있으며, 많은 경우에 종교에서 발견되었습니다. [31] 현대 사용에서 형이상학 적 우주론은 과학의 범위를 벗어난 우주에 관한 질문을 다룹니다. 변증법과 같은 철학적 방법을 사용하여 이러한 질문에 접근한다는 점에서 종교적 우주론과 구별됩니다. 현대 형이상학적 우주론은 다음과 같은 질문들을 다루려고 한다:[24][32]

- 우주의 기원은 무엇입니까? 첫 번째 원인은 무엇입니까? 그 존재가 필요합니까? (일원론, 범신론, 발산론 및창조론 참조)

- 우주의 궁극적인 물질적 구성 요소는 무엇입니까? (메커니즘, 역동성, 하이로모피즘, 원자론 참조)

- 우주가 존재하는 궁극적 인 이유는 무엇입니까? 우주에는 목적이 있습니까? (목적론 참조)

- 의식의 존재에는 목적이 있습니까? 우주의 총체성에 대해 우리가 아는 것을 어떻게 알 수 있습니까? 우주론적 추론은 형이상학적 진리를 드러내는가? (인식론 참조)

역사적 우주론편집하다

| 더 알아보세요

|

| 힌두교 우주론 | 리그베다(기원전 1700-1100년경) | 주기적 또는 진동, 시간의 무한 | 원시 물질은311.04 조 년 동안 나타나고 동일한 길이 동안나타나지 않습니다. 우주는43억 2천만 년동안 발현된 상태로 남아 있으며 동일한 기간 동안발현되지 않습니다. 무수한 우주가 동시에 존재합니다. 이러한 순환은 욕망에 의해 주도되어 영원히 지속될 것입니다. |

| Jain cosmology | Jain Agamas (written around 500 AD as per the teachings of Mahavira 599–527 BC) | Cyclical or oscillating, eternal and finite | Jain cosmology considers the loka, or universe, as an uncreated entity, existing since infinity, the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arm resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is broad at the top, narrow at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom. |

| Babylonian cosmology | Babylonian literature (c. 2300–500 BC) | Flat earth floating in infinite "waters of chaos" | The Earth and the Heavens form a unit within infinite "waters of chaos"; the earth is flat and circular, and a solid dome (the "firmament") keeps out the outer "chaos"-ocean. |

| Eleatic cosmology | Parmenides (c. 515 BC) | Finite and spherical in extent | The Universe is unchanging, uniform, perfect, necessary, timeless, and neither generated nor perishable. Void is impossible. Plurality and change are products of epistemic ignorance derived from sense experience. Temporal and spatial limits are arbitrary and relative to the Parmenidean whole. |

| Samkhya Cosmic Evolution | Kapila (6th century BC), pupil Asuri | Prakriti (Matter) and Purusha (Consiouness) Relation | Prakriti (Matter) is the source of the world of becoming. It is pure potentiality that evolves itself successively into twenty four tattvas or principles. The evolution itself is possible because Prakriti is always in a state of tension among its constituent strands known as gunas (Sattva (lightness or purity), Rajas (passion or activity), and Tamas (inertia or heaviness)). The cause and effect theory of Sankhya is called Satkaarya-vaada (theory of existent causes), and holds that nothing can really be created from or destroyed into nothingness—all evolution is simply the transformation of primal Nature from one form to another.[citation needed] |

| Biblical cosmology | Genesis creation narrative | Earth floating in infinite "waters of chaos" | The Earth and the Heavens form a unit within infinite "waters of chaos"; the "firmament" keeps out the outer "chaos"-ocean. |

| Atomist universe | Anaxagoras (500–428 BC) & later Epicurus | Infinite in extent | The universe contains only two things: an infinite number of tiny seeds (atoms) and the void of infinite extent. All atoms are made of the same substance, but differ in size and shape. Objects are formed from atom aggregations and decay back into atoms. Incorporates Leucippus' principle of causality: "nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and necessity". The universe was not ruled by gods.[citation needed] |

| Pythagorean universe | Philolaus (d. 390 BC) | Existence of a "Central Fire" at the center of the Universe. | At the center of the Universe is a central fire, around which the Earth, Sun, Moon and planets revolve uniformly. The Sun revolves around the central fire once a year, the stars are immobile. The earth in its motion maintains the same hidden face towards the central fire, hence it is never seen. First known non-geocentric model of the Universe.[33] |

| De Mundo | Pseudo-Aristotle (d. 250 BC or between 350 and 200 BC) | The Universe is a system made up of heaven and earth and the elements which are contained in them. | There are "five elements, situated in spheres in five regions, the less being in each case surrounded by the greater – namely, earth surrounded by water, water by air, air by fire, and fire by ether – make up the whole Universe."[34] |

| Stoic universe | Stoics (300 BC – 200 AD) | Island universe | The cosmos is finite and surrounded by an infinite void. It is in a state of flux, and pulsates in size and undergoes periodic upheavals and conflagrations. |

| Aristotelian universe | Aristotle (384–322 BC) | Geocentric, static, steady state, finite extent, infinite time | Spherical earth is surrounded by concentric celestial spheres. Universe exists unchanged throughout eternity. Contains a fifth element, called aether, that was added to the four classical elements. |

| Aristarchean universe | Aristarchus (circa 280 BC) | Heliocentric | Earth rotates daily on its axis and revolves annually about the sun in a circular orbit. Sphere of fixed stars is centered about the sun. |

| Ptolemaic model | Ptolemy (2nd century AD) | Geocentric (based on Aristotelian universe) | Universe orbits around a stationary Earth. Planets move in circular epicycles, each having a center that moved in a larger circular orbit (called an eccentric or a deferent) around a center-point near Earth. The use of equants added another level of complexity and allowed astronomers to predict the positions of the planets. The most successful universe model of all time, using the criterion of longevity. Almagest (the Great System). |

| Aryabhatan model | Aryabhata (499) | Geocentric or Heliocentric | The Earth rotates and the planets move in elliptical orbits around either the Earth or Sun; uncertain whether the model is geocentric or heliocentric due to planetary orbits given with respect to both the Earth and Sun. |

| Medieval universe | Medieval philosophers (500–1200) | Finite in time | A universe that is finite in time and has a beginning is proposed by the Christian philosopher John Philoponus, who argues against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past. Logical arguments supporting a finite universe are developed by the early Muslim philosopher Al-Kindi, the Jewish philosopher Saadia Gaon, and the Muslim theologian Al-Ghazali. |

| Non-Parallel Multiverse | Bhagvata Puran(800–1000) | Multiverse, Non Parallel | Innumerable universes is comparable to the multiverse theory, except nonparallel where each universe is different and individual jiva-atmas (embodied souls) exist in exactly one universe at a time. All universes manifest from the same matter, and so they all follow parallel time cycles, manifesting and unmanifesting at the same time.[35] |

| Multiversal cosmology | Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209) | Multiverse, multiple worlds and universes | There exists an infinite outer space beyond the known world, and God has the power to fill the vacuum with an infinite number of universes. |

| Maragha models | Maragha school (1259–1528) | Geocentric | Various modifications to Ptolemaic model and Aristotelian universe, including rejection of equant and eccentrics at Maragheh observatory, and introduction of Tusi-couple by Al-Tusi. Alternative models later proposed, including the first accurate lunar model by Ibn al-Shatir, a model rejecting stationary Earth in favour of Earth's rotation by Ali Kuşçu, and planetary model incorporating "circular inertia" by Al-Birjandi. |

| Nilakanthan model | Nilakantha Somayaji (1444–1544) | Geocentric and heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun, which orbits the Earth; similar to the later Tychonic system |

| Copernican universe | Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) | Heliocentric with circular planetary orbits | First described in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. |

| Tychonic system | Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) | Geocentric and Heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun and the Sun orbits the Earth, similar to the earlier Nilakanthan model. |

| Bruno's cosmology | Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) | Infinite extent, infinite time, homogeneous, isotropic, non-hierarchical | Rejects the idea of a hierarchical universe. Earth and Sun have no special properties in comparison with the other heavenly bodies. The void between the stars is filled with aether, and matter is composed of the same four elements (water, earth, fire, and air), and is atomistic, animistic and intelligent. |

| Keplerian | Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) | Heliocentric with elliptical planetary orbits | Kepler's discoveries, marrying mathematics and physics, provided the foundation for our present conception of the Solar system, but distant stars were still seen as objects in a thin, fixed celestial sphere. |

| Static Newtonian | Isaac Newton (1642–1727) | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle. Matter on the large scale is uniformly distributed. Gravitationally balanced but unstable. |

| Cartesian Vortex universe | René Descartes, 17th century | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | System of huge swirling whirlpools of aethereal or fine matter produces what we would call gravitational effects. But his vacuum was not empty; all space was filled with matter. |

| Hierarchical universe | Immanuel Kant, Johann Lambert, 18th century | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Matter is clustered on ever larger scales of hierarchy. Matter is endlessly recycled. |

| Einstein Universe with a cosmological constant | Albert Einstein, 1917 | Static (nominally). Bounded (finite) | "Matter without motion". Contains uniformly distributed matter. Uniformly curved spherical space; based on Riemann's hypersphere. Curvature is set equal to Λ. In effect Λ is equivalent to a repulsive force which counteracts gravity. Unstable. |

| De Sitter universe | Willem de Sitter, 1917 | Expanding flat space.Steady state. Λ > 0 | "Motion without matter." Only apparently static. Based on Einstein's general relativity. Space expands with constant acceleration. Scale factor increases exponentially (constant inflation). |

| MacMillan universe | William Duncan MacMillan 1920s | Static and steady state | New matter is created from radiation; starlight perpetually recycled into new matter particles. |

| Friedmann universe, spherical space | Alexander Friedmann 1922 | Spherical expanding space.k = +1 ; no Λ | Positive curvature. Curvature constant k = +1Expands then recollapses. Spatially closed (finite). |

| Friedmann universe, hyperbolic space | Alexander Friedmann, 1924 | Hyperbolic expanding space.k = −1 ; no Λ | Negative curvature. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). Unbounded. Expands forever. |

| Dirac large numbers hypothesis | Paul Dirac 1930s | Expanding | Demands a large variation in G, which decreases with time. Gravity weakens as universe evolves. |

| Friedmann zero-curvature | Einstein and De Sitter, 1932 | Expanding flat spacek = 0 ; Λ = 0 Critical density | Curvature constant k = 0. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). "Unbounded cosmos of limited extent". Expands forever. "Simplest" of all known universes. Named after but not considered by Friedmann. Has a deceleration term q = 1/2, which means that its expansion rate slows down. |

| The original Big Bang (Friedmann-Lemaître) | Georges Lemaître 1927–29 | ExpansionΛ > 0 ; Λ > |Gravity| | Λ is positive and has a magnitude greater than gravity. Universe has initial high-density state ("primeval atom"). Followed by a two-stage expansion. Λ is used to destabilize the universe. (Lemaître is considered the father of the Big Bang model.) |

| Oscillating universe (Friedmann-Einstein) | Favored by Friedmann, 1920s | Expanding and contracting in cycles | Time is endless and beginningless; thus avoids the beginning-of-time paradox. Perpetual cycles of Big Bang followed by Big Crunch. (Einstein's first choice after he rejected his 1917 model.) |

| Eddington universe | Arthur Eddington 1930 | First static then expands | Static Einstein 1917 universe with its instability disturbed into expansion mode; with relentless matter dilution becomes a De Sitter universe. Λ dominates gravity. |

| Milne universe of kinematic relativity | Edward Milne, 1933, 1935;William H. McCrea, 1930s | Kinematic expansion without space expansion | Rejects general relativity and the expanding space paradigm. Gravity not included as initial assumption. Obeys cosmological principle and special relativity; consists of a finite spherical cloud of particles (or galaxies) that expands within an infinite and otherwise empty flat space. It has a center and a cosmic edge (surface of the particle cloud) that expands at light speed. Explanation of gravity was elaborate and unconvincing. |

| Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker class of models | Howard Robertson, Arthur Walker, 1935 | Uniformly expanding | Class of universes that are homogeneous and isotropic. Spacetime separates into uniformly curved space and cosmic time common to all co-moving observers. The formulation system is now known as the FLRW or Robertson–Walker metrics of cosmic time and curved space. |

| Steady-state | Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold, 1948 | Expanding, steady state, infinite | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. Continuous creation out of nothing from nowhere. Exponential expansion. Deceleration term q = −1. |

| Steady-state | Fred Hoyle 1948 | Expanding, steady state; but unstable | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. But since matter creation rate must be exactly balanced with the space expansion rate the system is unstable. |

| Ambiplasma | Hannes Alfvén 1965 Oskar Klein | Cellular universe, expanding by means of matter–antimatter annihilation | Based on the concept of plasma cosmology. The universe is viewed as "meta-galaxies" divided by double layers and thus a bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic matter-antimatter annihilations keep the bubbles separated and moving apart preventing them from interacting. |

| Brans–Dicke theory | Carl H. Brans, Robert H. Dicke | Expanding | Based on Mach's principle. G varies with time as universe expands. "But nobody is quite sure what Mach's principle actually means."[citation needed] |

| Cosmic inflation | Alan Guth 1980 | Big Bang modified to solve horizon and flatness problems | Based on the concept of hot inflation. The universe is viewed as a multiple quantum flux – hence its bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic expansion kept the bubbles separated and moving apart. |

| Eternal inflation (a multiple universe model) | Andreï Linde, 1983 | Big Bang with cosmic inflation | Multiverse based on the concept of cold inflation, in which inflationary events occur at random each with independent initial conditions; some expand into bubble universes supposedly like our entire cosmos. Bubbles nucleate in a spacetime foam. |

| Cyclic model | Paul Steinhardt; Neil Turok 2002 | Expanding and contracting in cycles; M-theory. | Two parallel orbifold planes or M-branes collide periodically in a higher-dimensional space. With quintessence or dark energy. |

| Cyclic model | Lauris Baum; Paul Frampton 2007 | Solution of Tolman's entropy problem | Phantom dark energy fragments universe into large number of disconnected patches. Our patch contracts containing only dark energy with zero entropy. |

Table notes: the term "static" simply means not expanding and not contracting. Symbol G represents Newton's gravitational constant; Λ (Lambda) is the cosmological constant.

참고 항목편집하다

참조편집하다

- ^ Karl Hille, ed. (13 October 2016). "Hubble Reveals Observable Universe Contains 10 Times More Galaxies Than Previously Thought". NASA. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Hetherington, Norriss S. (2014). Encyclopedia of Cosmology (Routledge Revivals): Historical, Philosophical, and Scientific Foundations of Modern Cosmology. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-317-67766-6.

- ^ Luminet, Jean-Pierre (2008). The Wraparound Universe. CRC Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4398-6496-8. Extract of page 170

- ^ "Introduction: Cosmology – space". New Scientist. 4 September 2006

- ^ "Cosmology" Oxford Dictionaries

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (25 February 2019). "Have Dark Forces Been Messing With the Cosmos? – Axions? Phantom energy? Astrophysicists scramble to patch a hole in the universe, rewriting cosmic history in the process". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ David N. Spergel (Fall 2014). "Cosmology Today". Daedalus. 143 (4): 125–133. doi:10.1162/DAED_a_00312. S2CID 57568214.

- ^ Planck Collaboration (1 October 2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594 (13). Table 4 on page 31 of PDF. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830. S2CID 119262962.

- ^ Diderot (Biography), Denis (1 April 2015). "Detailed Explanation of the System of Human Knowledge". Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert – Collaborative Translation Project. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ The thoughts of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus viii. 52.

- ^ Einstein, A. (1952). "Cosmological considerations on the general theory of relativity". The Principle of Relativity. Dover Books on Physics. June 1, 1952. 240 Pages. 0486600815, P. 175-188: 175–188. Bibcode:1952prel.book..175E.

- ^ Dodelson, Scott (30 March 2003). Modern Cosmology. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-051197-9.

- ^ Falk, Dan (18 March 2009). "Review: The Day We Found the Universe by Marcia Bartusiak". New Scientist. 201 (2700): 45. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(09)60809-5. ISSN 0262-4079.

- ^ Hubble, E. P. (1 December 1926). "Extragalactic nebulae". The Astrophysical Journal. 64: 321. Bibcode:1926ApJ....64..321H. doi:10.1086/143018. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Martin, G. (1883). "G. DELSAULX. — Sur une propriété de la diffraction des ondes planes; Annales de la Société scientifique de Bruxelles; 1882". Journal de Physique Théorique et Appliquée (in French). 2 (1): 175. doi:10.1051/jphystap:018830020017501. ISSN 0368-3893.

- ^ 허블, 에드윈(1929년 3월 15일). "은하외 성운 사이의 거리와 반경 방향 속도 사이의 관계". 미국 국립 과학 아카데미의 회보. 15(3): 168–173. 참고 문헌 : 1929PNAS ... 15..168H. 도이 : 10.1073 / pnas.15.3.168. ISSN0027-8424. PMC522427. PMID16577160.

- ^ 펜지아스, A. A.; 윌슨, R. W. (1965년 7월 1일). "4080mc/s에서 초과 안테나 온도 측정". 천체 물리학 저널. 142: 419–421. Bibcode:1965ApJ... 142..419쪽. 도이 : 10.1086 / 148307. ISSN0004-637X.

- ^ 보게스, NW; 매더, JC.; 와이스, R.; 베넷, CL; 쳉, E. S.; 드웩, E.; 굴키스, S.; 하우저, M. G.; 얀센, MA; 켈솔, T.; 마이어, SS (1992년 10월 1일). "COBE 미션 – 출시 2 년 후 디자인 및 성능". 천체 물리학 저널. 397: 420–429. 참고 문헌 : 1992ApJ ... 397..420B. 도이 : 10.1086 / 171797. ISSN0004-637X.

- ^ Parker, Barry R. (1993). The vindication of the big bang : breakthroughs and barriers. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-44469-0. OCLC 27069165.

- ^ "Computer Graphics Achievement Award". ACM SIGGRAPH 2018 Awards. SIGGRAPH '18. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Association for Computing Machinery: 1. 12 August 2018. doi:10.1145/3225151.3232529. ISBN 978-1-4503-5830-9. S2CID 51979217.

- ^ Science, American Association for the Advancement of (15 June 2007). "NETWATCH: Botany's Wayback Machine". Science. 316 (5831): 1547. doi:10.1126/science.316.5831.1547d. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 220096361.

- ^ Paraficz, D.; Hjorth, J.; Elíasdóttir, Á (1 May 2009). "Results of optical monitoring of 5 SDSS double QSOs with the Nordic Optical Telescope". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 499 (2): 395–408. arXiv:0903.1027. Bibcode:2009A&A...499..395P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811387. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Alan Guth is reported to have made this very claim in an Edge Foundation interview EDGE Archived 11 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "BICEP2 2014 Results Release". National Science Foundation. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Whitney Clavin (17 March 2014). "NASA Technology Views Birth of the Universe". NASA. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Dennis Overbye (17 March 2014). "Detection of Waves in Space Buttresses Landmark Theory of Big Bang". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Dennis Overbye (19 June 2014). "Astronomers Hedge on Big Bang Detection Claim". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (19 June 2014). "Cosmic inflation: Confidence lowered for Big Bang signal". BBC News. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Ade, P. A. R.; Aikin, R. W.; Barkats, D.; Benton, S. J.; Bischoff, C. A.; Bock, J. J.; Brevik, J. A.; Buder, I.; Bullock, E.; Dowell, C. D.; Duband, L.; Filippini, J. P.; Fliescher, S.; Golwala, S. R.; Halpern, M.; Hasselfield, M.; Hildebrandt, S. R.; Hilton, G. C.; Hristov, V. V.; Irwin, K. D.; Karkare, K. S.; Kaufman, J. P.; Keating, B. G.; Kernasovskiy, S. A.; Kovac, J. M.; Kuo, C. L.; Leitch, E. M.; Lueker, M.; Mason, P.; et al. (2014). "Detection of B-Mode Polarization at Degree Angular Scales by BICEP2". Physical Review Letters. 112 (24): 241101. arXiv:1403.3985. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.112x1101B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.241101. PMID 24996078. S2CID 22780831.

- ^ Dennis Overbye (1 December 2014). "New Images Refine View of Infant Universe". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ 크라우치, CL (2010년 2월 8일). "창세기 1 : 26-7 인류의 신성한 혈통에 대한 진술로서". 신학 연구 저널. 61(1): 1–15. 도이 : 10.1093 / JTS / FLP185.

- ^ "출판물 – 코스모스". www.cosmos.esa.int. 2018년 8월 19일에 확인함.

- ^ 칼 B. 보이어(1968), 수학의 역사. 윌. ISBN0471543977. 피. 54.

- ^ 아리스토텔레스 (1914). 포스터, ES; 돕슨, JF (eds.). 드 문도. 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 393a.

- ^ 미라벨로, 마크 (2016년 9월 15일). 내세에 대한 여행자 가이드 : 죽음, 죽음, 그리고 그 너머에있는 것에 대한 전통과 신념. 사이먼과 슈스터. 피. 23. ISBN978-1-62055-598-9.

외부 링크편집하다

- NASA / IPAC 은하계 데이터베이스 (NED) (NED-Distances)

- 우주 여행: 과학적 우주론의 역사Archived2008년 10월 21일 -웨이백 머신- 미국 물리학 연구소

- 우주론 입문 David Lyth의 ICTP Summer School of High Energy Physics and Cosmology 강의

- 소피아 센터 웨일즈 대학교 트리니티 세인트 데이비드 문화의 우주론 연구를위한 소피아 센터

- 창세기우주 화학모듈

- "The Universe's Shape", BBC 라디오 4에서 마틴 리스 경, 줄리안 바버, 잔나 레빈과 토론 (In Our Time, 2002년 2월 7일)