환원운동(회복/복원 등으로 해석가능함)

복원 운동 (미국 복원 운동 또는 스톤 캠벨 운동이라고도 함)은 19 세기 초의 두 번째 대각성 (1790-1840) 동안 미국 국경에서 시작된 기독교 운동입니다. 이 운동의 선구자들은 내부로부터 교회를 개혁하려고 애썼고[1] "신약 교회를 본뜬 한 몸으로 모든 그리스도인들의 통일"을 추구했다. [2]: 54

회복 운동은 초기 기독교를 이상화 한 종교적 부흥의 여러 독립적 인 가닥에서 발전했습니다. 기독교 신앙에 대해 독립적으로 유사한 접근법을 개발 한 두 그룹이 특히 중요했습니다. [3] Barton W. Stone이 이끄는 첫 번째 사람은 켄터키 주 Cane Ridge에서 시작하여 "기독교인"으로 확인되었습니다. 두 번째는 펜실베이니아 서부와 버지니아 (현재 웨스트 버지니아)에서 시작되었으며 토마스 캠벨과 그의 아들 알렉산더 캠벨 (Alexander Campbell)이 이끌었고 둘 다 스코틀랜드에서 교육을받았다. 그들은 결국 "그리스도의 제자"라는 이름을 사용했습니다. 두 집단 모두 신약성경에 제시된 가시적인 패턴에 기초하여 전체 기독교 교회를 회복시키려고 노력했으며, 둘 다 신조가 기독교를 분열시킨다고 믿었다. 1832년에 그들은 악수로 교제에 참여했다.

무엇보다도 그들은 예수분이 하나님의 아들이신 그리스도이시라는 믿음 안에서 연합되었습니다. 그리스도인들은 매주 첫째 날에 주의 만찬을 거행해야 한다. 그리고 성인 신자들의 세례는 필연적으로 물에 잠기는 것에 의한 것이었다. [4]: 147~148 창립자들은 모든 교파의 명칭을 포기하기를 원했기 때문에, 그들은 예수의 추종자들을 위해 성경적 이름을 사용했다. [4]: 27 두 집단 모두 신약성경에 묘사된 대로 1세기 교회의 목적으로의 복귀를 장려했다. 이 운동의 한 역사가는 그것이 주로 통일 운동이라고 주장했으며, 복원 모티프는 종속 된 역할을한다고 주장했다. [5]: 8

회복 운동은 이후 여러 그룹으로 나뉘어져 있습니다. 세 가지 주요 그룹은 그리스도의 교회, 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자) 및 독립적 인 기독교 교회 / 그리스도 교회 회중입니다. 또한 국제 그리스도 교회, 국제 기독교 교회, 유럽의 그리스도 교회, 캐나다의 복음주의 기독교 교회,[6][7][8] 그리고 호주에는 그리스도의 교회가 있습니다. 어떤 사람들은 회복과 에큐메니즘의 목표 사이의 긴장의 결과로 운동의 분열을 특징 짓는다 : 그리스도의 교회와 무소속 기독교 교회 / 그리스도 교회는 회복을 강조함으로써 긴장을 해결했으며, 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자들)는 에큐메니즘을 강조함으로써 긴장을 해결했다. [5]: 383

목차

운동의 이름[편집]

회복 운동은 다른 지도자가있는 다양한 장소에서 시작된 중앙 집중식 구조가 없기 때문에 운동 전체에 대한 일관된 명명법이 없습니다. [9] "회복 운동"이라는 용어는 19 세기에 인기를 얻었다. [10] 이것은 알렉산더 캠벨의 에세이가 기독교 침례교에서 "고대 사물 질서의 회복"에 영향을 미쳤기 때문인 것으로 보인다. [10] "스톤 캠벨 운동"이라는 용어는 사용 된 다른 이름 중 일부와 관련된 어려움을 피하고 운동의 집단적 역사에 대한 감각을 유지하는 방법으로 19 세기 말에 등장했습니다. [10]

핵심 원칙[편집]

회복 운동은 몇 가지 핵심 원칙으로 특징 지어졌습니다.

- 기독교는 분열되어서는 안되며, 그리스도는 하나의 교회를 창조하려고 의도하셨습니다. [3]: 38 [11]

- 신조는 분열되지만, 그리스도인들은 성경 자체에 서서 합의를 찾을 수 있어야 한다(그로부터 모든 신조는 인간의 팽창이나 수축에 불과하다고 믿는다)[12]

- 교회 전통은 분열되지만, 그리스도인들은 초대 교회의 실천(가능한 한 최선을 다하여)을 따름으로써 공통점을 찾을 수 있어야 한다. [13]: 104–6

- 인간 기원의 이름은 분열되지만, 기독교인들은 교회를 위해 성경적 이름을 사용함으로써 공통점을 찾을 수 있어야 한다(즉, "감리교"나 "루터교" 등과 반대되는 "기독교 교회", "하나님의 교회" 또는 "그리스도의 교회" 등). [4]: 27

따라서 교회는 '모든 그리스도인들이 공통적으로 가지고 있는 것만을 강조해야 하며, 모든 분열적인 교리와 관습을 억압해야 한다'. [14]

회복 운동에는 여러 가지 슬로건이 사용되었는데, 이는 운동의 독특한 주제 중 일부를 표현하기위한 것입니다. [15] 여기에는 다음이 포함됩니다.

- "성경이 말하는 곳에서는 우리가 말합니다. 성경이 침묵하는 곳에서는 침묵합니다." [16]

- "지상에 있는 예수 그리스도의 교회는 본질적으로, 의도적으로, 그리고 헌법적으로 하나입니다." [16]

- "우리는 기독교인일 뿐, 유일한 기독교인은 아닙니다." [16]

- "본질적으로, 단결; 의견, 자유; 범사에 사랑하라." [15]: 688

- "그리스도 외에는 신조가 없고, 성경 외에는 책도 없고, 율법도 사랑도 없고, 이름도 없고 신성하지도 않다." [15]: 688

- "성경의 방법으로 성경의 일을 행하라." [15]: 688

- "성경의 이름을 성경의 이름으로 부르십시오." [15]: 688

배경 영향[편집]

중세 후기에 존 위클리프와 존 후스와 같은 반대자들은 원시적인 형태의 기독교의 회복을 요구했지만, 그들은 지하로 몰려들었다. 결과적으로, 그러한 초기 반대자들과 회복 운동 사이의 직접적인 연관성을 찾기가 어렵습니다. [13]: 13

르네상스부터 지적 뿌리는 식별하기가 더 쉬워집니다. [17] 종교개혁의 핵심은 "성경만"(솔라 스크립투라)의 원칙을 강조하는 것이었다. [18] 이것은 개인이 스스로 성경을 읽고 해석 할 권리에 대한 주장과 함께 예배에서의 의식을 줄이기위한 운동과 함께 초기 회복 운동 지도자들의 지적 배경의 일부를 형성했다. [19] Huldrych Zwingli와 John Calvin으로 대표되는 종교 개혁 운동의 지부는 "성경적 형태와 패턴을 복원"하는 데 중점을 두었습니다. [20]

존 로크의 합리주의는 또 다른 영향을 미쳤다. [21] 로크는 허버트 경의 이신론에 반응하여 성경을 포기하지 않고 종교적 분열과 박해를 해결할 방법을 모색했다. [21] 이를 위해 로크는 종교적 정통성을 강제할 정부의 권리에 반대하며 모든 그리스도인들이 동의할 수 있는 일련의 믿음을 제공하기 위해 성경으로 향했다. [22]그가 본질적이라고 여겼던 핵심 가르침은 예수의 메시아와 예수의 직접적인 명령이었다. [22] 기독교인들은 다른 성경적 가르침들에 독실하게 헌신할 수 있었지만, 로크의 관점에서 볼 때, 이것들은 그리스도인들이 결코 서로 싸우거나 강요하려고 해서는 안 되는 비본질적인 것들이었다. [23] 청교도들과 후대의 회복 운동과는 달리, 로크는 초대 교회의 체계적인 회복을 요구하지 않았다. [23]

영국 청교도들의 기본 목표 중 하나는 진정한 사도 공동체가 될 순수하고 "원시적인"교회를 복원하는 것이 었습니다. [24] 이 개념은 식민지 미국에서 청교도들의 발전에 결정적인 영향을 미쳤다. [25]

그것은 "미국에서 가장 오래된 에큐메니칼 운동"으로 묘사되어 왔다:[26]

이 운동의 위대한 창립 문서는 모두 진정한 에큐메니칼입니다. 스프링필드 노회의 마지막 뜻과 유언장(1804)에서 바튼 스톤과 그의 동료 부흥주의자들은 "그리스도의 몸과 연합하여 가라앉기"를 바라면서, 그들의 배타적인 노회적 관계를 해산시켰다. 다섯 년 후 토마스 캠벨은 워싱턴 기독교 협회의 선언과 연설 [PA] (1809)에서 "지구상의 그리스도의 교회는 본질적으로, 의도적으로 그리고 헌법적으로 하나"라고 썼다. [1]

첫 번째 대각성 동안, 분리 침례교로 알려진 침례교인들 사이에서 운동이 발전했다. 이 운동의 두 가지 주제는 신조에 대한 거부와 "성령 안에서의 자유"였습니다. [27] 분리된 침례교인들은 성경을 교회의 "완전한 규칙"으로 보았다. [28]그러나 그들은 교회를 위한 구조적 패턴을 찾기 위해 성경에 의지했지만, 그 패턴의 세부 사항에 대한 완전한 합의를 고집하지는 않았다. [29] 이 집단은 뉴잉글랜드에서 기원되었지만, 특히 남부에서는 교회를 위한 성경적 패턴에 대한 강조가 더욱 강해졌다. [29] 18세기 후반에 켄터키와 테네시의 서쪽 국경에서 분리된 침례교인들이 더 많아졌고, 그곳에서 스톤과 캠벨 운동이 나중에 뿌리를 내렸다. [30] 남부 국경에서 분리된 침례교인들의 발전은 회복 운동의 토대를 마련하는 데 도움이 되었다. 스톤과 캠벨 그룹의 구성원은 분리 침례교의 계급에서 크게 벗어났습니다. [29]

분리 된 침례교 복원주의는 또한 스톤 캠벨 복원 운동과 거의 동시에 같은 지역에서 랜드 마크 침례교의 발전에 기여했습니다. 제임스 로빈슨 그레이브스 (James Robinson Graves)의 지도력하에,이 그룹은 원시 교회에 대한 정확한 청사진을 정의하기를 원했으며, 그 청사진에서 벗어나면 사람이 참된 교회의 일부가되는 것을 막을 것이라고 믿었습니다. [30]

기독교의 "원시적인"형태를 복원하는 이상은 미국 혁명 이후 미국에서 인기를 얻었습니다. [31] 더 순수한 형태의 기독교를 회복하려는 이러한 열망은 두 번째 위대한 각성으로 알려진이 기간 동안 많은 집단의 발전에 중요한 역할을했다. [32] 여기에는 예수 그리스도 후기 성도 교회, 침례교 및 셰이커교가 포함되었다. [32]

회복 운동은 이 두 번째 각성 동안에 시작되었고, 크게 영향을 받았다. [33] 캠벨들은 캠프 모임의 영적 조작으로 보았던 것에 저항했지만, 각성의 남쪽 단계는 "바튼 스톤의 개혁 운동의 중요한 매트릭스"였으며 스톤과 캠벨이 사용하는 복음 주의적 기술을 형성했다. [34]

제임스 오켈리(James O'Kelly)는 신약 기독교로의 복귀를 통해 일치를 추구하는 초기 옹호자였다. [35]: 216 1792년, 감리교 성공회에서 감독의 역할에 불만을 품은 그는 그 몸에서 헤어졌다. 버지니아와 노스캐롤라이나를 중심으로 한 오켈리의 운동은 원래 공화당 감리교인이라고 불렸다. 1794년에 그들은 기독교 교회라는 이름을 채택했다. [36]

같은 기간 동안 버몬트의 엘리어스 스미스와 뉴햄프셔의 애브너 존스는 오켈리와 비슷한 견해를 지지하는 운동을 이끌었다. [30][37] 그들은 회원들이 성경만을 바라봄으로써 인간의 전통과 유럽에서 온 이민자들이 가져온 교파에 얽매이지 않고 단순히 기독교인이 될 수 있다고 믿었다. [30][37]: 190

돌 운동[편집]

| 위키소스에는 이 기사와 관련된 원본 텍스트가 있습니다. |

Barton W. Stone은 1772년 12월 24일 메릴랜드 주 포트 담배 근처에서 존과 메리 워렌 스톤 사이에서 태어났다. [38]: 702 그의 직계 가족은 메릴랜드의 상류층과 인연이 있는 중산층이었다.[38]: 702 바튼의 아버지는 1775년에 사망하였고, 그의 어머니는 1779년에 가족을 버지니아 주 피츠실베니아 카운티로 옮겼다. [38]: 702 메리 스톤은 영국 교회의 회원이었고, 바튼은 토마스 손튼이라는 사제에 의해 세례를 받았다. 버지니아로 이주한 후 그녀는 감리교에 합류했다. [39]: 52 바튼은 청년으로서 특별히 종교적이지 않았다. 그는 성공회, 침례교 및 감리교인들의 경쟁적인 주장이 혼란 스럽다는 것을 알았고 정치에 훨씬 더 관심이있었습니다. [39]: 52~53 (미국 혁명 이후 영국 교회는 해체되었고 성공회는 조직되었다.)

Barton은 1790 년 노스 캐롤라이나의 Guilford Academy에 입학했습니다. [5]: 71 그곳에 있는 동안, 스톤은 제임스 맥그레디(장로교 목사)가 말하는 것을 들었다. [5]: 72 몇 년 후, 그는 장로교 목사로 성임되었다. [5]: 72 그러나 스톤은 장로교인들의 믿음들, 특히 웨스트민스터 신앙고백의 믿음들을 더 깊이 들여다보면서, 교회 신앙들 중 일부가 진실로 성경에 기초한 것이라는 것을 의심하였다. [5]: 72~3 그는 완전한 타락, 무조건적인 선택, 예정에 대한 칼빈주의 교리를 받아들일 수 없었다. [5]: 72~3 그는 또한 "칼빈주의의 주장된 신학적 정교함은... 분열을 조장하는 대가로 샀다"며 "비난했다. 장로교 전통에서만 열 개의 다른 종파를 생산하기 위해서입니다." [40]: 110

지팡이 리지 부흥[편집]

1801년, 켄터키의 지팡이 리지 부흥회는 켄터키와 오하이오 강 계곡에서 교단주의와 단절하기 위한 운동을 위한 씨앗을 심었다. 1803년 스톤과 다른 사람들은 켄터키 노회에서 물러나 스프링필드 노회를 결성했다. 운동의 돌 날개의 결정적인 사건은 1804 년 켄터키 주 지팡이 리지 (Cane Ridge)에서 스프링 필드 노회의 마지막 의지와 유언장을 출판 한 것입니다. 마지막 뜻은 스톤과 다섯 명의 다른 사람들이 장로교에서 철수하고 그리스도의 몸의 일부일 뿐이라고 발표한 간단한 문서입니다. [41] 저자들은 예수을 따르는 모든 사람들의 일치를 호소하고, 회중 자치의 가치를 제안했으며, 하나님의 뜻을 이해하는 근원으로 성경을 들어 올렸다. 그들은 웨스트민스터 신앙고백의 '분열적인' 사용을 비난했고,[4]:79 그들의 집단을 식별하기 위해 "기독교인"이라는 이름을 채택했다. [4]: 80

기독교 연결[편집]

By 1804 Elias Smith had heard of the Stone movement, and the O'Kelly movement by 1808.[37]: 190 The three groups merged by 1810.[37]: 190 At that time the combined movement had a membership of approximately 20,000.[37]: 190 This loose fellowship of churches was called by the names "Christian Connection/Connexion" or "Christian Church."[13]: 68 [37]: 190

Characteristics of the Stone movement[edit]

The cornerstone for the Stone movement was Christian freedom.[13]: 104 This ideal of freedom led them to reject all the historical creeds, traditions and theological systems that had developed over time and to focus instead on a primitive Christianity based on the Bible.[13]: 104–5

While restoring primitive Christianity was central to the Stone movement, they believed that restoring the lifestyle of members of the early church is essential. During the early years, they "focused more... on holy and righteous living than on the forms and structures of the early church.[13]: 103 The group also worked to restore the primitive church.[13]: 104 Due to concern that emphasizing particular practices could undermine Christian freedom, this effort tended to take the form of rejecting tradition rather than an explicit program of reconstructing New Testament practices.[13]: 104 The emphasis on freedom was so strong that the movement avoided developing any ecclesiastical traditions; it was "largely without dogma, form, or structure."[13]: 104–5 What held "the movement together was a commitment to primitive Christianity."[13]: 105

Another theme was that of hastening the millennium.[13]: 104 Many Americans of the period believed that the millennium was near and based their hopes for the millennium on their new nation, the United States.[13]: 104 Members of the Stone movement believed that only a unified Christianity based on the apostolic church, rather than a country or any of the existing denominations, could lead to the coming of the millennium.[13]: 104 Stone's millennialism has been described as more "apocalyptic" than that of Alexander Campbell, in that he believed people were too flawed to usher in a millennial age through human progress.[42]: 6, 7 Rather, he believed that it depended on the power of God, and that while waiting for God to establish His kingdom, one should live as if the rule of God were already fully established.[42]: 6

For the Stone movement, this millennial emphasis had less to do with eschatological theories and more about a countercultural commitment to live as if the kingdom of God were already established on earth.[42]: 6, 7 This apocalyptic perspective or world view led many in the Stone movement to adopt pacifism, avoid participating in civil government, and reject violence, militarism, greed, materialism and slavery.[42]: 6

Campbell movement[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Campbell wing of the movement was launched when Thomas Campbell published the Declaration and Address of the Christian Association of Washington in 1809.[4]: 108–11 The Presbyterian Synod had suspended his ministerial credentials. In The Declaration and Address, he set forth some of his convictions about the church of Jesus Christ. He organized the Christian Association of Washington, in Washington County, Pennsylvania on the western frontier of the state, not as a church but as an association of persons seeking to grow in faith.[4]: 108–11 On May 4, 1811, the Christian Association reconstituted itself as a congregationally governed church. With the building it constructed at Brush Run, Pennsylvania, it became known as Brush Run Church.[4]: 117

When their study of the New Testament led the reformers to begin to practice baptism by immersion, the nearby Redstone Baptist Association invited Brush Run Church to join with them for the purpose of fellowship. The reformers agreed, provided that they would be "allowed to preach and to teach whatever they learned from the Scriptures."[43]: 86

Thomas' son Alexander came to the US to join him in 1809.[13]: 106 Before long, he assumed the leading role in the movement.[13]: 106

The Campbells worked within the Redstone Baptist Association during the period 1815 through 1824. While both the Campbells and the Baptists shared practices of baptism by immersion and congregational polity, it quickly became clear the Campbells and their associates were not traditional Baptists. Within the Redstone Association, some of the Baptist leaders considered the differences intolerable when Alexander Campbell began publishing a journal, The Christian Baptist, which promoted reform. Campbell anticipated the conflict and moved his membership to a congregation of the Mahoning Baptist Association in 1824.[4]: 131

알렉산더는 기독교 침례교를 사용하여 사도적 기독교 공동체를 체계적이고 합리적인 방식으로 재건하는 핵심 쟁점으로 보았던 것을 다루었다. [13]: 106 그는 원시적 기독교의 본질적인 측면과 필수적이지 않은 측면들을 명확하게 구별하기를 원하였다. [13]: 106 그가 본질적이라고 밝힌 것 중에는 "회중 자치, 각 회중의 복수 장로, 매주 친교와 죄 사함을 위한 침수"가 있었다. [13]: 106 그가 필수적이지 않다고 거부한 관습들 중에는 "거룩한 입맞춤, 집사, 공동체 생활, 발 씻기, 카리스마 넘치는 운동"이 있었다. [13]: 106

1827년 마호닝 협회는 월터 스콧을 전도사로 임명했다. 스콧의 노력을 통해 마호닝 협회는 빠르게 성장했다. 1828년, 토마스 캠벨은 스콧이 결성한 여러 회중을 방문하여 그의 설교를 들었다. 캠벨은 스콧이 전도에 대한 그의 접근 방식을 통해 운동에 중요한 새로운 차원을 가져오고 있다고 믿었다. [4]: 132–3

몇몇 침례교 단체들은 필라델피아 고해성사에 가입하기를 거부한 회중들을 분리시키기 시작했다. [44] 마호닝 협회는 공격을 받았다. 1830년, 마호닝 침례교 협회는 해산되었다. 젊은 캠벨은 기독교 침례교의 출판을 중단했다. 1831년 1월, 그는 밀레니얼 세대 하빙거(Millennial Harbinger)를 출판하기 시작했다. [4]: 144–5

계몽주의의 영향[편집]

계몽주의 시대는 캠벨 운동에 중요한 영향을 미쳤다. [13]: 80~6 토마스 캠벨은 계몽주의 철학자 존 로크의 학생이었다. [13]: 82 토마스는 선언과 연설에서 "본질"이라는 용어를 명시적으로 사용하지는 않았지만, 허버트와 로크가 이전에 발전시켰던 것과 같은 종교적 분열에 대한 동일한 해결책을 제안했다: "종교를 모든 합리적인 사람들이 동의할 수 있는 일련의 본질에 이르게 한다." [13]: 80 그가 확인한 본질은 성경이 제시한 관습들이었다: "'주께서 이렇게 말씀하시는' 것은 표현적인 용어나 승인된 선례에 의하여." [13]: 81 청교도들의 초기 노력이 본질적으로 분열적이라고 생각했던 로크와는 달리, 토마스는 "사도적 기독교의 완전한 회복"을 주장했다. [13]: 82 토마스는 신조가 그리스도인들을 분열시키는 데 도움이 된다고 믿었다. 그는 또한 성경이 누구나 이해할 수 있을 만큼 충분히 명확하며, 따라서 신조는 불필요하다고 믿었다. [45]:114

알렉산더 캠벨 (Alexander Campbell)은 계몽주의 사상, 특히 토마스 리드 (Thomas Reid)와 듀갈드 스튜어트 (Dugald Stewart)의 스코틀랜드 상식 학교에 깊은 영향을 받았다. [13]: 84 이 집단은 성경이 추상적인 진리보다는 구체적인 사실들을 연관시킨다고 믿었고, 성경을 해석하는 과학적 또는 "베이코니아적" 접근법을 옹호했다. 그것은 그러한 사실들로 시작하고, 주어진 주제에 적용 가능한 것들을 배열하고, "성경에 적용된 과학적 방법 이상"으로 묘사 된 방식으로 결론을 이끌어 낼 것입니다. [13]: 84 알렉산더는 "성경은 의견, 이론, 추상적 일반성, 언어적 정의가 아니라 사실의 책"이라고 거듭 주장하면서 이러한 베이코니아적 접근법을 반영했다. [13]: 84 사실에 대한 의존이 과학자들 사이의 합의의 기초를 제공하는 것처럼, 알렉산더는 기독교인들이 성경에 나오는 사실들에 한정한다면 필연적으로 합의에 이르게 될 것이라고 믿었다. [13]: 84 그는 이성적이고 과학적인 방식으로 접근한 그러한 사실들이 교회에 청사진이나 헌법을 제공한다고 믿었다. [13]: 85 알렉산더는 성경에 대한 이러한 과학적 접근에 매료되었는데, 그 이유는 성경이 기독교적 일치를 위한 신뢰할 수 있는 기초를 제공했기 때문이다. [13]: 84

캠벨 운동의 특징[편집]

토마스 캠벨은 연합에 대한 계몽주의 접근법을 개혁주의 및 청교도 회복의 전통과 결합시켰다. [13]: 82, 106 계몽주의는 캠벨 운동에 두 가지 방법으로 영향을 미쳤다. 첫째, 그것은 모든 합리적인 사람들이 동의 할 수있는 일련의 필수 요소를 발견함으로써 기독교 일치가 달성 될 수 있다는 생각을 제공했습니다. 둘째, 그것은 또한 성경에서 파생 된 사실에 근거하여 공식화되고 옹호 된 합리적인 신앙의 개념을 제공했습니다. [13]: 85, 86 캠벨이 기독교 일치를 이루기 위한 해결책은 그가 믿었던 신조와 전통을 버리고 모든 그리스도인들에게 공통적인 성경에서 발견되는 원시적 기독교를 회복하는 것을 결합했다. [13]: 106

알렉산더 캠벨의 밀레니엄 세대주의는 스톤보다 낙관적이었다. [42]: 6 그는 인간 진보의 잠재력에 대해 더 많은 확신을 가지고 있었고, 그리스도인들이 단합하여 세상을 변화시키고 천년시대를 시작할 수 있다고 믿었다. [42]: 6 캠벨의 개념은 천년기 이후였는데, 그는 교회와 사회의 진보가 그리스도의 재림 전에 평화와 의의 시대로 이어질 것이라고 예상했기 때문이다. [42]: 6 이 낙관적 접근은, 원시주의에 대한 그의 헌신 이외에도, 그의 사고에 진보적인 가닥을 가지고 있다는 것을 의미했다. [42]: 7

스톤과 캠벨 운동의 합병[편집]

캠벨 운동은 급진적 인 자유와 교리의 부족을 특징으로하는 스톤 운동과는 달리 초기 교회의 "체계적이고 합리적인 재구성"을 특징으로했습니다. [46] 그들의 차이에도 불구하고, 두 운동은 몇 가지 중요한 쟁점에 동의했다. [47] 둘 다 사도적 기독교를 회복하는 것을 천년을 서두르는 수단으로 보았다. [47] 둘 다 또한 초대 교회를 기독교의 자유로 가는 길로 회복시키는 것을 보았다. [47]그리고 둘 다 그리스도인들 사이의 일치는 사도적 기독교를 모델로 사용함으로써 성취될 수 있다고 믿었다. [47] 초대 교회를 회복하고 그리스도인들을 연합시키려는 두 운동의 헌신은 두 운동의 많은 사람들 사이의 연합에 동기를 부여하기에 충분했다. [42]: 8, 9

스톤과 캠벨 운동은 1832 년에 합병되었습니다. [3]: 28 [43]: 116–20 [48]: 212 [49] 이것은 켄터키 주 렉싱턴에 있는 힐 스트리트 미팅 하우스에서 바튼 W 스톤과 "너구리" 존 스미스 사이의 악수로 공식화되었다. [43]: 116~20 스미스는 참석자들에 의해 캠벨 추종자들의 대변인으로 선출되었다. [43]: 116 1831년 12월 말에 두 그룹의 예비 회의가 열렸고, 1832년 1월 1일에 합병으로 절정에 달했다. [43]: 116–20 [50]

총회의 두 대표는 모든 교회들에게 연합의 소식을 전하기 위해 임명되었다: 존 로저스, 기독교인들을 위한 그리고 개혁자들을 위한 "너구리" 존 스미스. 몇 가지 도전에도 불구하고 합병은 성공했습니다. [4]: 153~4 많은 사람들은 노조가 연합운동의 장래의 성공에 대한 큰 약속을 가지고 있다고 믿었고, 그 소식을 열렬히 환영했다. [42]: 9

스톤과 알렉산더 캠벨의 개혁자들(제자와 기독교 침례교라고도 함)이 1832년에 연합했을 때, 스미스/존스와 오켈리 운동의 소수의 기독교인들만이 참여했다. [51]그렇게 한 사람들은 애팔래치아 산맥 서쪽의 회중 출신으로, 돌 운동과 접촉했다. [51] 동부 회원들은 스톤과 캠벨 그룹과 몇 가지 중요한 차이점을 가지고 있었다: 개종 경험에 대한 강조, 친교의 분기별 준수, 그리고 비삼위일체론. [51] 캠벨과 연합하지 않은 사람들은 1931년에 회중 교회들과 합병하여 회중 기독교 교회들을 형성하였다. [52] 1957년에, 회중 기독교 교회는 그리스도의 연합 교회가 되기 위하여 복음주의 및 개혁 교회와 합병했다. [52]

연합 운동 (1832-1906)[편집]

합병은 새로운 운동을 무엇이라고 부를 것인가에 대한 질문을 제기했다. 성경적이고 비종파적인 이름을 찾는 것이 중요했다. 스톤은 "기독교인"이라는 이름을 계속 사용하기를 원했고, 알렉산더 캠벨은 "그리스도의 제자들"을 주장했다. [4]: 27~8 [53] 스톤은 사도행전 11:26에서 "그리스도인들"이라는 이름을 사용하는 것을 옹호했지만, 캠벨은 "제자"라는 용어를 더 겸손하고 오래된 명칭으로 보았기 때문에 "제자"라는 용어를 선호했다. [10] 그 결과 두 이름이 모두 사용되었고, 이름에 대한 혼란은 그 이후로 계속되었다. [4]: 27–8

1832 년 이후, "종교 개혁"이라는 용어의 사용은 운동의 지도자들 사이에서 빈번하게되었다. [10] 캠벨들은 자신들을 "개혁가들"로 지정했고, 다른 초기 지도자들 또한 자신들을 기독교적 일치를 추구하고 사도적 기독교를 회복시키는 개혁가로 보았다. [10] 당시 운동의 언어에는 "종교 개혁", "현재의 개혁", "현재의 개혁"및 "개혁의 원인"과 같은 문구가 포함되어있었습니다. [10] "회복 운동"이라는 용어는 19 세기가 진행됨에 따라 대중화되었다. [10] 그것은 알렉산더 캠벨 (Alexander Campbell)의 기독교 침례교 (Christian Baptist)의 "고대 사물 질서의 회복"에 관한 에세이에서 영감을 얻은 것으로 보인다. [10]

결합 운동은 1832 년부터 1906 년까지 빠르게 성장했습니다. [54] : 92-93 [55] : 25 1906 년 미국 종교 인구 조사에 따르면이 운동의 결합 된 회원 자격은 그 당시 미국에서 6 번째로 큰 기독교 단체가되었습니다. [55]: 27

예상 회원 수년18321860189019001906| 회원 자격 | 22,000[54]: 92 | 192,000[54]: 92 | 641,051[55]: 25 | 1,120,000[54]: 93 | 1,142,359[55]: 25 |

저널[편집]

제자들에게는 감독이 없습니다. 그들은 장로가 있습니다.

- 초기 운동 역사가 윌리엄 토마스 무어[56]

운동의 시작부터, 사람들 사이의 자유로운 아이디어 교환은 지도자들이 출판 한 저널에 의해 촉진되었습니다. 알렉산더 캠벨 (Alexander Campbell)은 기독교 침례교와 밀레니엄 세대 하빙거 (The Millennial Harbinger)를 출판했습니다. 스톤은 크리스챤 메신저를 출판했다. [48]: 208 두 사람 모두 자신의 입장과 근본적으로 다른 사람들의 공헌을 일상적으로 출판했다.

1866년 캠벨이 사망한 후, 저널은 토론을 계속하기 위해 사용되었다. 1870년과 1900년 사이에, 두 개의 저널이 가장 두드러진 것으로 떠올랐다. 기독교 표준은 오하이오 주 신시내티의 아이작 에렛 (Isaac Errett)에 의해 편집되고 출판되었습니다. 기독교 전도사는 세인트 루이스의 JH 개리슨에 의해 편집되고 출판되었습니다. 두 사람은 우호적 인 경쟁을 즐겼고 대화 상대를 운동 내에서 계속 유지했습니다. [48]:364

The Gospel Advocate was founded by the Nashville-area preacher Tolbert Fanning in 1855.[57] Fanning's student, William Lipscomb, served as co-editor until the American Civil War forced them to suspend publication in 1861.[58] After the end of the Civil War, publication resumed in 1866 under the editorship of Fanning and William Lipscomb's younger brother David Lipscomb; Fanning soon retired and David Lipscomb became the sole editor.[59] While David Lipscomb was the editor, the focus was on seeking unity by following scripture exactly, and the Advocate's editorial position was to reject anything that is not explicitly allowed by scripture.[60]

The Christian Oracle began publication in 1884. It was later known as The Christian Century and offered an interdenominational appeal.[48]: 364 In 1914, Garrison's Christian Publishing company was purchased by R.A. Long. He established a non-profit corporation, "The Christian Board of Publication" as the Brotherhood publishing house.[48]: 426

Anabaptism and materialism controversies[edit]

|

|

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The Christadelphians, Church of the Blessed Hope, and Church of God (General Conference) also have roots in the restoration movement, but took their own direction about this time.

In 1832 Walter Scott baptised John Thomas, an English doctor who had emigrated to the United States. Thomas was a strong supporter of Alexander Campbell and the principles of the Disciples movement, and he quickly became a well-known leader and teacher. In 1834, however, Thomas took a contrary position to Alexander Campbell on the significance of baptism which led to a sharp conflict between the two men. While Campbell believed baptism by immersion to be very important, he recognised as Christians all who believed Jesus of Nazareth to be Messiah and Lord, and recognised any prior baptism. For this reason, members of Baptist churches who joined the Disciples movement were not required to be baptised again. Thomas, on the other hand, insisted that a baptism based on a different understanding of the gospel to that held in the Disciples movement was not a valid baptism, and called for rebaptism in his periodical, the Apostolic Advocate. Campbell viewed this as sectarianism, which cut across the fundamental commitment of the Disciples movement to "the union of all Christians," and rejected "anabaptism." The two men became estranged.

Thomas began to refuse to share prayer, worship, or communion with those he considered not to be validly baptised Christians. His theological views also continued to develop. By 1837 he was teaching annihilationism, and debated a Presbyterian clergymen, Isaac Watts. Campbell interpreted this as materialism, and believed that it undermined the biblical doctrine of the resurrection, and reacted strongly. In the Millennial Harbinger he announced that he could no longer consider Thomas a brother. Many congregations of Disciples took this as an indication that they should withhold fellowship from Thomas, and he found himself on the margins of the movement.

Thomas continued to have supporters among the Disciples, but moved further and further from Christian orthodoxy. In 1846 he published a "Confession and Abjuration" of the faith he held at his baptism, and arranged to be baptised again. Despite this, when he toured the United Kingdom to give prophetic lectures in 1848–1850 he played down his separation from the Disciples movement, in an endeavour to access congregations in Britain. But his true position was discovered by James Wallis and David King, and the movement closed ranks against him.

In 1864 he coined the name "Christadelphian" for those who shared his views and sought to register as conscientious objectors to military service. The new name was adopted by Robert Roberts, the Scottish protege of Thomas, for the periodical which he had just begun to publish in Birmingham; and the sect began to grow rapidly.

Benjamin Wilson left the Disciples about the same time as Thomas, but split with Thomas in 1863 over disagreements about eschatology, forming the Church of God of the Abrahamic Faith. During the American Civil War his followers also sought to register as conscientious objectors. Some congregations were unable to register this name due to local regulations, and chose an alternative name, Church of the Blessed Hope; but the two names referred to the same sect. The sect divided in 1921, and the Church of God (General Conference) was formed by the larger grouping.

Missionary society controversy[edit]

In 1849, the first National Convention was held at Cincinnati, Ohio.[48]: 245 Alexander Campbell had concerns that holding conventions would lead the movement into divisive denominationalism. He did not attend the gathering.[48]: 245 Among its actions, the convention elected Alexander Campbell its president and created the American Christian Missionary Society (ACMS).[48]: 247 By the end of the century, the Foreign Christian Missionary Society and the Christian Woman's Board of Missions were also engaged in missionary activities. Forming the ACMS did not reflect a consensus of the entire movement, and these para-church organizations became a divisive issue. While there was no disagreement over the need for evangelism, many believed that missionary societies were not authorized by scripture and would compromise the autonomy of local congregations.[61]

The ACMS was not as successful as proponents had hoped.[62] It was opposed by those who believed any extra-congregational organizations were inappropriate; hostility grew when the ACMS took a stand in 1863 favoring the Union side during the American Civil War.[62][63] A convention held in Louisville, Kentucky in 1869 adopted a plan intended to address "a perceived need to reorganize the American Christian Missionary Society (ACMS) in a way that would be acceptable to more members of the Movement."[62] The "Louisville Plan," as it came to be known, attempted to build on existing local and regional conventions and to "promote the harmonious cooperation of all the state and District Boards and Conventions."[62][64] It established a General Christian Missionary Convention (GCMC).[64] Membership was congregational rather than individual.[62][64] Local congregations elected delegates to district meetings, which in turn elected delegates to state meetings.[62] States were given two delegates, plus an additional delegate for every 5,000 members.[62] The plan proved divisive, and faced immediate opposition.[62][64] Opponents continued to argue that any organizational structure above the local congregational level was not authorized by scripture, and there was a general concern that the Board had been given too much authority.[62] By 1872 the Louisville Plan had effectively failed.[62][64] Direct contributions from individuals were sought again in 1873, individual membership was reinstated in 1881, and the name was changed back to the American Christian Missionary Society in 1895.[62][64]

Use of musical instruments in worship[edit]

The use of musical instruments in worship was discussed in journal articles as early as 1849, but initial reactions were generally unfavorable.[65]: 414 Some congregations, however, are documented as having used musical instruments in the 1850s and 1860s.[65]: 414 An example is the church in Midway, Kentucky, which was using an instrument by 1860.[65]: 414 A member of the congregation, L. L. Pinkerton, brought a melodeon into the church building.[65]: 414 [66]: 95, 96 [67]: 597–598 The minister had been distressed to his "breaking point" by the poor quality of the congregation's singing.[66]: 96 At first, the instrument was used for singing practices held on Saturday night, but was soon used during the worship on Sunday.[66]: 96 One of the elders of that assembly removed the first melodeon, but it was soon replaced by another.[66]: 96

Both acceptance of instruments and discussion of the issue grew after the American Civil War.[65]: 414 Opponents argued that the New Testament provided no authorization for their use in worship, while supporters argued on the basis of expediency and Christian liberty.[65]: 414 Affluent, urban congregations were more likely to adopt musical instruments, while poorer and more rural congregations tended to see them as "an accommodation to the ways of the world."[65]: 414

The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement notes that Restoration Movement historians have tended to interpret the controversy over the use of musical instruments in worship in ways that "reflect their own attitudes on the issue."[65]: 414 Examples are given of historians from different branches of the movement interpreting it in relation to the statements of early Restoration Movement leaders, in terms of social and cultural factors, differing approaches to interpreting scripture, differing approaches to the authority of scripture, and "ecumenical progressivism" versus "sectarian primitivism."[65]: 414–5

Role of clergy[edit]

The early 19th-century Restoration Movement encompassed very different views concerning the role of clergy: the Campbell branch was strongly anti-clergy, believing there was no justification for a clergy/lay distinction, while the Stone branch believed that only an ordained minister could officiate at communion.[54]

Biblical interpretation[edit]

Early leaders of the movement had a high view of scripture, and believed that it was both inspired and infallible.[68] Dissenting views developed during the 19th century.[68] As early as 1849, LL Pinkerton denied the inerrancy of the Bible.[67][68] According to the Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement Pinkerton is "sometimes labeled the first 'liberal' of the Stone-Campbell Movement."[67] In addition to rejecting the plenary inspiration of the Bible and supporting the use of instruments in worship, Pinkerton also supported "open membership" (recognizing as members individuals who have not been baptized by immersion)[69] and was a strong supporter of the temperance and abolition movements.[67] As the 19th century progressed, the denial of the inerrancy of the Bible slowly spread.[68] In 1883 the editor of the Christian Standard, Isaac Errett, said "Admitting the fact of inspiration, have we in the inspired Scriptures an infallible guide?... I do not see how we can answer this question affirmatively."[68] Others, including JW McGarvey, fiercely opposed these new liberal views.[68]

Separation of the Churches of Christ and Christian Churches[edit]

Nothing in life has given me more pain in heart than the separation from those I have heretofore worked with and loved

— David Lipscomb, 1899[70]

Factors leading to the separation[edit]

Disagreement over centralized organizations above the local congregational level, such as missionary societies and conventions, was one important factor leading to the separation of the Churches of Christ from the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[61] After the American Civil War more congregations began using instruments, which led to growing controversy.[65]: 414 The greatest acceptance was among urban congregations in the Northern states; very few congregations in the Southern United States used instruments in worship.[65]: 414–415

While music and the approach to missionary work were the most visible issues, there were also some deeper ones, such as basic differences in the underlying approach to Biblical interpretation. For the Churches of Christ, any practices not present in accounts of New Testament worship were not permissible in the church, and they could find no New Testament documentation of the use of instrumental music in worship. For the Christian Churches, any practices not expressly forbidden could be considered.[4]: 242–7 The American Civil War exacerbated the cultural tensions between the two groups.[71]

As the 19th century progressed, a division gradually developed between those whose primary commitment was to unity, and those whose primary commitment was to the restoration of the primitive church.[42]: 5, 6 Those whose primary focus was unity gradually took on "an explicitly ecumenical agenda" and "sloughed off the restorationist vision."[42]: 6 This group increasingly used the terms "Disciples of Christ" and "Christian Churches" rather than "Churches of Christ."[42]: 6 At the same time, those whose primary focus was restoration of the primitive church increasingly used the term "Churches of Christ" rather than "Disciples of Christ."[42]: 6 Reports on the changes and increasing separation among the groups were published as early as 1883.[4]: 252

The rise of women leaders in the temperance[72]: 728–729 and missionary movements, primarily in the North, also contributed to the separation of the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations. In the Christian Churches, many women spoke in public on behalf of the new Christian Woman's Board of Missions (CWBM) and Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). In contrast, the Churches of Christ largely discouraged women from joining activist women's organizations such as the WCTU and speaking in public about any issue.[73]: 292–316 In 1889 the Erie Christian Church confirmed the leadership role of women by ordaining Clara Babcock as the first known woman Disciple preacher.[74]: 47–60

Formal recognition in 1906[edit]

The United States Census Bureau began a religious census in 1906.[75][76] Special Agents were used to collect information on those groups which had little or no formal organizational structure, such as the churches associated with the Restoration Movement.[75][76] Officials working on the census noticed signs that the movement was no longer unified: the Gospel Advocate appeared at times to distance itself from the Disciples of Christ, and the Bureau had received at least one letter claiming that some "churches of Christ" were no longer affiliated with the "Disciples of Christ."[75][76]

To resolve the question, the Census Director, Simon Newton Dexter North, wrote a letter to David Lipscomb, the editor of the Advocate.[75][76] He asked:

I would like to know: 1. Whether there is a religious body called "Church of Christ," not identified with the Disciples of Christ, or any other Baptist body? 2. If there is such a body, has it any general organization, with headquarters, officers, district or general conventions, associations or conferences? 3. How did it originate, and what are its distinctive principles? 4. How best can there be secured a complete list of the churches?[76]

Lipscomb summarized the early history of the movement, described the "general organization of the churches under a missionary society with a moneyed membership" and the "adoption of instrumental music in the worship" as "a subversion of the fundamental principles on which the churches were based," and then continued:[76]

There is a distinct people taking the word of God as their only and sufficient rule of faith, calling their churches "churches of Christ" or "churches of God," distinct and separate in name, work, and rule of faith from all other bodies of people.[75][76]

The 1906 U.S. Religious Census for the first time listed the "Churches of Christ" and the "Disciples of Christ" as separate and distinct groups.[4]: 251 This, however, was simply the recognition of a division that had been growing for years, with published reports as early as 1883.[4]: 252 The process that led to this separation had begun prior to the American Civil War.[77]: 17–8

For Lipscomb, an underlying theological concern was the adoption of German liberal theology by many among the Disciples wing of the Restoration Movement.[78] He saw them as taking a direction very different from the principles enunciated by Thomas and Alexander Campbell.[78] Lipscomb's response to the Census Bureau, and its official listing of the two groups in 1906, became another source of friction between the groups.[75][76] James Harvey Garrison, editor of the "Disciples" journal, The Christian-Evangelist, accused Lipscomb of "sectarianism." Lipscomb said that he had "done nothing to bring about the present condition of affairs," the Census Bureau had started the discussion, and he had simply answered the question they brought to him.[75][76]

Movement historian Douglas Foster has summarized the events this way:

The data reflected what had already happened (and what continued to happen for at least another decade). The Census Bureau itself had noticed a rift between Churches of Christ and Disciples of Christ, and in the interest of reliable data collection tried to ascertain if that was true. Lipscomb agreed that it was accurate to list the two separately; Garrison did not. The division did not begin or happen in 1906 — it was nearing its end. The government did not declare the division; the Census Bureau simply published data it received.[75]

Aftermath[edit]

When the 1906 U.S. Religious Census was published in 1910 it reported combined totals for the "Disciples or Christians" for comparison to the 1890 statistics on the movement, as well as separate statistics for the "Disciples of Christ" and the "Churches of Christ."[55] The Disciples were by far the larger of the two groups at the time.[55]: 28, 514

Relative Size of Disciples of Christ and Churches of Christ in 1906Congregations[55]: 514 Members[55]: 28| "Disciples of Christ" | 8,293 (75.8%) | 982,701 (86.0%) |

| "Churches of Christ" | 2,649 (24.2%) | 159,658 (14.0%) |

| Total "Disciples or Christians" | 10,942 | 1,142,359 |

Generally speaking, the Disciples of Christ congregations tended to be predominantly urban and Northern, while the Churches of Christ were predominantly rural and Southern. The Disciples favored college-educated clergy, while the Churches of Christ discouraged formal theological education because they opposed the creation of a professional clergy. Disciples congregations tended to be wealthier and constructed larger, more expensive church buildings. Churches of Christ congregations built more modest structures, and criticized the wearing of expensive clothing at worship.[54]: 109 One commentator has described the Disciples "ideal" as reflecting the "businessman," and the Church of Christ "ideal" as reflecting "the simple and austere yeoman farmer."[54]: 109

Churches of Christ have maintained an ongoing commitment to purely congregational structure, rather than a denominational one, and have no central headquarters, councils, or other organizational structure above the local church level.[79]: 214 [5]: 449 [45]: 124 [80]: 238 [81]: 103 [82] The Disciples developed in a different direction. After a number of discussions throughout the 1950s, the 1960 International Convention of Christian Churches adopted a process to "restructure" the entire organization.[83] The Disciples restructured in a way that has been described as an "overt recognition of the body's denominational status,"[84]: 268 resulting in what has been described as "a Reformed North American Mainstream Moderate Denomination."[85]

After the separation from the Churches of Christ, tensions remained among the Disciples of Christ over theological liberalism, the nascent ecumenical movement and "open membership."[86]: 185 While the process was lengthy, the more conservative unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations eventually emerged as a separately identifiable religious body from the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[86]: 185

Some commentators believe divisions in the movement have resulted from the tension between the goals of restoration and ecumenism, and see the Churches of Christ and unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations resolving the tension by stressing restoration while the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) resolve the tension by stressing ecumenism.[79]: 210 [5]: 383

All of the three major U.S. branches of the Movement share the following characteristics:

- A high view, compared to other Christian traditions, of the office of the elder; and[87]: 532

- A "commitment to the priesthood of all believers".[87]: 532

The term "restoration movement" has remained popular among the Churches of Christ and the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations.[9]: 551 Because of the emphasis it places on the theme of restoration, it has been a less comfortable fit for those whose primary focus has been on the theme of unity.[9]: 551 Historically, the term "Disciples of Christ" has also been used by some as a collective designation for the movement.[9]: 551 It has evolved, however, into a designation for a particular branch of the movement – the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) – as a result of the divisions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[9]: 551

The movement as a whole grew significantly over the course of the 20th century, and the relative size of the different groups associated with the movement shifted as well.[88]

Relative Size of Restoration Movement Groups in 2000[88]CongregationsMembers| Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) | 3,625 | 785,776 |

| Unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations | 5,293 | 1,453,160 |

| Churches of Christ | 12,584 | 1,584,162 |

| International Churches of Christ | 450 | 120 000 |

Subsequent development of the Christian Churches[edit]

Following the 1906 separation of the Churches of Christ, controversy still existed within the movement over whether the missionary efforts should be cooperative or independently sponsored by congregations. Questions on the role of the methods of Biblical Criticism to the study and interpretation of the Bible were also among the issues in conflict.[48]: 418–20 An awareness of historical criticism began developing in the 1880s, and by the 1920s many Disciples accepted the work of the higher critics.[89]: 178 By that time the question of "open membership," or "admission of the pious unimmersed to membership" had arisen as an additional source of tension.[89]: 182 [90]: 63

During the first half of the 20th century the opposing factions among the Christian Churches coexisted, but with discomfort. The three Missionary Societies were merged into the United Christian Missionary Society in 1920.[48]: 428, 429 Human service ministries grew through the National Benevolent Association providing assistance to orphans, the elderly and the disabled. By mid century, the cooperative Christian Churches and the independent Christian Churches were following different paths.

By 1926 a split began to form within the Disciples over the future direction of the church. Conservatives within the group began to have problems with the perceived liberalism of the leadership, upon the same grounds described earlier in the accepting of instrumental music in worship. In 1927 they held the first North American Christian Convention, and the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations began to emerge as a distinct group from the Disciples, although the break was not totally formalized until the late 1960s. By this time the decennial religious census was a thing of the past and it is impossible to use it as a delineation as it was in 1906.

Following World War II, it was believed that the organizations that had been developed in previous decades no longer effectively met the needs of the postwar era.[4]: 419 After a number discussions throughout the 1950s, the 1960 International Convention of Christian Churches adopted a process to plan the "restructure" of the entire organization.[4]: 421 The Commission on Restructure, chaired by Granville T. Walker, held its first meeting October 30 & November 1, 1962.[4]: 436–37 In 1968, at the International Convention of Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ), those Christian Churches that favored cooperative mission work adopted a new "provisional design" for their work together, becoming the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[5]: 495 Those congregations that chose not to be associated with the new denominational organization went their own way as the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations, completing a separation that had begun decades before.[5]: 407–9

The Disciples of Christ still have their own internal conservative-liberal tension. In 1985, a movement of conservative congregations and individuals among the Disciples formed the "Disciple Renewal."[91]: 272 They thought that others in the Disciples fellowship had increasingly liberal views on issues such as the lordship of Christ, the authority of the Bible, and tolerance of homosexuality.[91]: 272 In 1985 the Disciples General Assembly rejected a resolution on the inspiration of scripture; afterward, the Disciple Renewal planned to encourage renewal from within the fellowship through founding a journal entitled Disciple Renewal.[91]: 272 Conservative members were concerned that the Disciples had abandoned the fundamental principles of the Restoration Movement.[91]: 272

In 1995 the Disciple Heritage Fellowship[92] was established. It is a fellowship of autonomous congregations, about half of which are formally associated with the Disciples of Christ.[91]: 272 As of 2002 the Disciples Heritage Fellowship included 60 congregations and 100 "supporting" churches.[91]: 272

Restructuring and development of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)[edit]

In 1968, the International Convention of Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ) adopted the commission's proposed "Provisional Design of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)."[4]: 442–43 The restructuring was implemented in 1969 by the first General Assembly, and the name officially changed to the "Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)".[93]: 645 This restructuring has been described as an "overt recognition of the body's denominational status,"[84]: 268 and the modern Disciples have been described as "a Reformed North American Mainstream Moderate Denomination."[85]

Membership trends[edit]

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) has experienced a significant loss of membership since the middle of the 20th century. Membership peaked in 1958 at just under 2 million.[94] In 1993, membership dropped below 1 million. In 2009, the denomination reported 658,869 members in 3,691 congregations.[94] As of 2010, the five states with the highest adherence rates were Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Kentucky and Oklahoma.[95] The states with the largest absolute number of adherents were Missouri, Texas, Indiana, Kentucky and Ohio.[96]

Subsequent development of the unaffiliated congregations[edit]

Independent Christian churches and churches of Christ have both organizational and hermeneutic differences with the churches of Christ.[79]: 186 For example, they have a loosely organized convention, and they view scriptural silence on an issue more permissively.[79]: 186 Nonetheless, they are much more closely related to the churches of Christ in their theology and ecclesiology than they are with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[79]: 186

The development of the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations as a separately identifiable religious body from the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) (DoC) was a lengthy process.[86]: 185 The roots of the separation can be found in the polarization resulting from three major controversies that arose during the early 20th century.[86]: 185 One, which was a source of division in other religious groups, was "the theological development of modernism and liberalism."[86]: 185 The early stages of the ecumenical movement, which led in 1908 to the Federal Council of Churches, provide a second source of controversy.[86]: 185 The third was the practice of open membership, in which individuals who had not been baptized by immersion were granted full membership in the church.[86]: 185 Those who supported one of these points of view tended to support the others as well.[86]: 185

The Disciples of Christ were, in 1910, a united, growing community with common goals.[97] Support by the United Christian Missionary Society of missionaries who advocated open membership became a source of contention in 1920.[86]: 185 Efforts to recall support for these missionaries failed in a 1925 convention in Oklahoma City and a 1926 convention in Memphis, Tennessee.[86]: 185 Many congregations withdrew from the missionary society as a result.[86]: 185

A new convention, the North American Christian Convention, was organized by the more conservative congregations in 1927.[86]: 185 An existing brotherhood journal, the Christian Standard, also served as a source of cohesion for these congregations.[86]: 185 From the 1960s on, newer unaffiliated missionary organizations like the Christian Missionary Fellowship (today, Christian Missionary Fellowship International) were working more on a national scale in the United States to rally Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations in international missions.[86]: 9 By this time the division between liberals and conservatives was well established.[97]

The official separation between the independent Christian churches and churches of Christ and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is difficult to date.[5]: 407 Suggestions range from 1926 to 1971 based on the events outlined below:

- 1926: The first North American Christian Convention (NACC) in 1927[5]: 407 was the result of disillusionment at the DoC Memphis Convention.

- 1944: International Convention of Disciples elects as president a proponent of open membership[5]: 408

- 1948: The Commission on Restudy, appointed to help avoid a split, disbands[5]: 409

- 1955: The Directory of the Ministry was first published listing only the "Independents" on a voluntary basis.[5]: 408

- 1968: Final redaction of the Disciples Year Book removing Independent churches[5]: 408

- 1971: Independent churches listed separately in the Yearbook of American Churches.[5]: 408

Because of this separation, many independent Christian churches and churches of Christ are not only non-denominational, they can be anti-denominational, avoiding even the appearance or language associated with denominationalism holding true to their Restoration roots.

Subsequent development of the Churches of Christ[edit]

One of the issues leading to the 1906 separation was the question of organizational structures above the level of the local congregation. Since then, Churches of Christ have maintained an ongoing commitment to church governance that is congregational only, rather than denominational. Churches of Christ purposefully have no central headquarters, councils, or other organizational structure above the local church level.[79]: 214 [45]: 124 [80]: 238 [81]: 103 [98] Rather, the independent congregations are a network with each congregation participating at its own discretion in various means of service and fellowship with other congregations (see Sponsoring church (Churches of Christ)).[45]: 124 [99][100][101] Churches of Christ are linked by their shared commitment to restoration principles.[81]: 106 [99]

Since Churches of Christ are autonomous and purposefully do not maintain an ecclesiastical hierarchy or doctrinal council, it is not unusual to find variations from congregation to congregation. There are many notable consistencies, however; for example, very few Church of Christ buildings display a cross, a practice common in other Christian churches. The approach taken to restoring the New Testament church has focused on "methods and procedures" such as church organization, the form of worship, and how the church should function. As a result, most divisions among Churches of Christ have been the result of "methodological" disputes. These are meaningful to members of this movement because of the seriousness with which they take the goal of "restoring the form and structure of the primitive church."[79]: 212

Three quarters of the congregations and 87% of the membership are described by The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement as "mainstream", sharing a consensus on practice and theology.[102]: 213 The remaining congregations may be grouped into four categories which generally differ from the mainstream consensus in specific practices, rather than in theological perspectives, and tend to have smaller congregations on average.[102]: 213

The largest of these four categories is the "non-institutional" churches of Christ. This group is notable for opposing congregational support of institutions such as orphans homes and Bible colleges. Approximately 2,055 congregations fall in this category.[102]: 213 [103]

The remaining three groups, whose congregations are generally considerably smaller than those of the mainstream or "non-institutional" groups, also oppose institutional support but differ from the "non-institutional" group by other beliefs and practices:[102]: 213 [103]

- One group opposes separate "Sunday School" classes; this group consists of approximately 1,100 congregations.

- Another group opposes the use of multiple communion cups (the term "one-cupper" is often used, sometimes pejoratively, to describe this group); there approximately 550 congregations in this group and this group overlaps somewhat with those congregations that oppose separate Sunday School classes.

- The last and smallest group "emphasize[s] mutual edification by various leaders in the churches and oppose[s] one person doing most of the preaching." This group includes roughly 130 congregations.

While there are no official membership statistics for the Churches of Christ, growth appears to have been relatively steady through the 20th century.[42]: 4 One source estimates total US membership at 433,714 in 1926, 558,000 in 1936, 682,000 in 1946, 835,000 in 1965 and 1,250,000 in 1994.[42]: 4

Separation of the International Churches of Christ[edit]

The International Churches of Christ (ICOC) had their roots in a "discipling" movement that arose among the mainline Churches of Christ during the 1970s.[104]: 418 This discipling movement developed in the campus ministry of Chuck Lucas.[104]: 418

In 1967, Chuck Lucas was minister of the 14th Street Church of Christ in Gainesville, Florida (later renamed the Crossroads Church of Christ). That year he started a new project known as Campus Advance (based on principles borrowed from the Campus Crusade and the Shepherding Movement). Centered on the University of Florida, the program called for a strong evangelistic outreach and an intimate religious atmosphere in the form of soul talks and prayer partners. Soul talks were held in student residences and involved prayer and sharing overseen by a leader who delegated authority over group members. Prayer partners referred to the practice of pairing a new Christian with an older guide for personal assistance and direction. Both procedures led to "in-depth involvement of each member in one another's lives", and critics accused Lucas of fostering cultism.[105]

The Crossroads Movement later spread into some other Churches of Christ. One of Lucas' converts, Kip McKean, moved to the Boston area in 1979 and began working with the Lexington Church of Christ.[104]: 418 He asked them to "redefine their commitment to Christ," and introduced the use of discipling partners. The congregation grew rapidly, and was renamed the Boston Church of Christ.[104]: 418 In the early 1980s, the focus of the movement moved to Boston, Massachusetts where Kip McKean and the Boston Church of Christ became prominently associated with the trend. With the national leadership located in Boston, during the 1980s it commonly became known as the "Boston movement."[104]: 418

In 1990 the Crossroads Church of Christ broke with the Boston movement and, through a letter written to The Christian Chronicle, attempted to restore relations with the mainline Churches of Christ.[104]: 419 By the early 1990s some first-generation leaders had become disillusioned by the movement and left.[104]: 419 The movement was first recognized as an independent religious group in 1992 when John Vaughn, a church growth specialist at Fuller Theological Seminary, listed them as a separate entity.[106] TIME magazine ran a full-page story on the movement in 1992 calling them "one of the world's fastest-growing and most innovative bands of Bible thumpers" that had grown into "a global empire of 103 congregations from California to Cairo with total Sunday attendance of 50,000".[107]

A formal break was made from the mainline Churches of Christ in 1993 when the movement organized under the name "International Churches of Christ."[104]: 418 This new designation formalized a division that was already in existence between those involved with the Crossroads/Boston Movement and "mainline" Churches of Christ.[5][104]: 418 Other names that have been used for this movement include the "Crossroads movement," "Multiplying Ministries," and the "Discipling Movement".[105]

Reunion efforts[edit]

Efforts have been made to restore unity among the various branches of the Restoration Movement. In 1984 a "Restoration Summit" was held at the Ozark Christian College, with fifty representatives of both the Churches of Christ and the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations.[108]: 642 Later meetings were open to all, and were known as "Restoration Forums."[108]: 642 Beginning in 1986 they have been held annually, generally in October or November, with the hosting venue alternating between the Churches of Christ and the Christian churches and churches of Christ.[108]: 642 Topics discussed have included issues such as instrumental music, the nature of the church, and practical steps for promoting unity.[108]: 642 Efforts have been made in the early 21st century to include representatives of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[108]: 642 These efforts followed the "Stone-Campbell Dialogue," which was a series of meetings beginning in 1999 that included representatives of all three major US branches of the Restoration Movement.[108]: 642 [109]: 720 The first full meeting in 1999 included six representatives from each of the three traditions.[109]: 720 Meetings were held twice annually, and in 2001 were expanded to include anyone associated with the Restoration Movement who was interested in attending.[109]: 720 Also, special efforts were made in 2006 to create more intentional fellowship between the various branches of the Movement.[110][111] This was in conjunction with the one hundredth anniversary of the "official" recognition of the split between the Christian Church and the Churches of Christ by the U.S. Census in 1906.[110][111] One example of this was the hosting by Abilene Christian University (ACU) of the annual Restoration Unity Forum for 2006 as part of the university's annual Bible Lectureship.[112] During the program Don Jeanes, president of Milligan College and Royce Money, president of ACU, jointly gave a presentation on the first chapter of the Gospel of John.[113]

Timeline[edit]

|

↓The American Christian Missionary Society (ACMS)

│

1800

│

1820

│

1840

│

1860

│

1880

│

1900

│

1920

│

1940

│

1960

│

1980

│

2000

│

2020

|

Churches outside North America[edit]

Restoration Movement churches are found around the world and the World Convention of Churches of Christ provides many national profiles.[114]

Their genealogies are representative of developments in North America. Their theological orientation ranges from fundamentalist to liberal to ecumenical. In some places they have joined with churches of other traditions to form united churches at local, regional or national level.[citation needed]

Africa[edit]

There are believed to be 1,000,000 or more members of the Churches of Christ in Africa.[102]: 212 The total number of congregations is approximately 14,000.[115]: 7 The most significant concentrations are in "Nigeria, Malawi, Ghana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, South Africa and Kenya".[115]: 7

Asia[edit]

India has historically been a target for missionary efforts; estimates are that there are 2,000 or more Restoration Movement congregations in India,[116]: 37, 38 with a membership of approximately 1,000,000.[102]: 212 More than 100 congregations exist in the Philippines.[116]: 38 Growth in other Asian countries has been smaller but is still significant.[116]: 38

Australia and New Zealand[edit]

Historically, Restoration Movement groups from Great Britain were more influential than those from the United States in the early development of the movement in Australia.[117]: 47 Churches of Christ grew up independently in several locations.[117]: 47

While early Churches of Christ in Australia saw creeds as divisive, towards the end of the 19th century they began viewing "summary statements of belief" as useful in tutoring second generation members and converts from other religious groups.[117]: 50 The period from 1875 through 1910 also saw debates over the use of musical instruments in worship, Christian Endeavor Societies and Sunday Schools. Ultimately, all three found general acceptance in the movement.[117]: 51

Currently, the Restoration Movement is not as divided in Australia as it is in the United States.[117]: 53 There have been strong ties with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), but many conservative ministers and congregations associate with the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations instead.[117]: 53 Others have sought support from non-instrumental Churches of Christ, particularly those who felt that "conference" congregations had "departed from the restoration ideal."[117]: 53

Great Britain[edit]

A group in Nottingham withdrew from the Scotch Baptist church in 1836 to form a Church of Christ.[118]: 369 James Wallis, a member of that group, founded a magazine named The British Millennial Harbinger in 1837.[118]: 369 In 1842 the first Cooperative Meeting of Churches of Christ in Great Britain was held in Edinburgh.[118]: 369 Approximately 50 congregations were involved, representing a membership of 1,600.[118]: 369 The name "Churches of Christ" was formally adopted at an annual meeting in 1870.[118]: 369 Alexander Campbell influenced the British Restoration Movement indirectly through his writings; he visited the Britain for several months in 1847, and "presided at the Second Cooperative Meeting of the British Churches at Chester."[118]: 369 At that time the movement had grown to encompass 80 congregations with a total membership of 2,300.[118]: 369 Annual meetings were held after 1847.[118]: 369

The use of instrumental music in worship was not a source of division among the Churches of Christ in Great Britain before World War I. More significant was the issue of pacifism; a national conference was established in 1916 for congregations that opposed the war.[118]: 371 A conference for "Old Paths" congregations was first held in 1924.[118]: 371 The issues involved included concern that the Christian Association was compromising traditional principles in seeking ecumenical ties with other organizations and a sense that it had abandoned Scripture as "an all-sufficient rule of faith and practice."[118]: 371 Two "Old Paths" congregations withdrew from the Association in 1931; an additional two withdrew in 1934, and nineteen more withdrew between 1943 and 1947.[118]: 371

Membership declined rapidly during and after the First World War.[118]: 372 [118]: 372 [119]: 312 The Association of Churches of Christ in Britain disbanded in 1980.[118]: 372 [119]: 312 Most Association congregations (approximately 40) united with the United Reformed Church in 1981.[118]: 372 [119]: 312 In the same year, twenty-four other congregations formed a Fellowship of Churches of Christ.[118]: 372 The Fellowship developed ties with the unaffiliated Christian Church/Church of Christ congregations during the 1980s.[118]: 372 [119]: 312

The Fellowship of Churches of Christ and some Australian and New Zealand Churches advocate a "missional" emphasis with an ideal of "Five Fold Leadership." Many people in more traditional Churches of Christ see these groups as having more in common with Pentecostal churches. The main publishing organs of traditional Churches of Christ in Britain are The Christian Worker magazine and the Scripture Standard magazine. A history of the Association of Churches of Christ, Let Sects and Parties Fall, was written by David M Thompson.[120]

Key figures[edit]

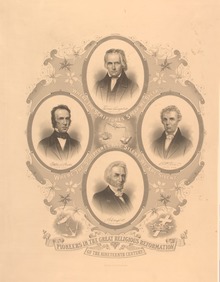

Although Barton W. Stone, Thomas and Alexander Campbell, and Walter Scott were to become the best-known and most influential early leaders of the movement, others preceded them and laid the foundation for their work.

- Rice Haggard (1769–1819)[121]

- James O'Kelly (1735?–1826), Durham, North Carolina[122]

- Abner Jones (1772–1841)[123]

- Barton W. Stone (1772–1844)[124]

- Elias Smith (1764–1846)[125]

- Thomas Campbell (1763–1854)[126]

- Walter Scott (1796–1861), a successful evangelist who helped to stabilize the Campbell movement as it was separating from the Baptists[127][128]

- Alexander Campbell (1788–1866)[129]

- "Raccoon" John Smith (1784–1868), instrumental in bringing the Stone and Campbell movements together[130]

- Elijah Martindale (1793–1874), active in Indiana[131][132]

- Amos Sutton Hayden (1813–1880)[133]

- James A. Garfield (1831–1881), first Restoration Movement member to be elected United States President, the others being Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973) and Ronald Reagan (1911–2004)

- Marshall Keeble (1878–1969) His successful preaching career notably bridged a racial divide in the Restoration Movement prior to the American Civil Rights Movement.[134][135]

- Kip McKean (born 1954), founder of the International Churches of Christ (ICOC), a twentieth-century offshoot of this movement

- List of Notable Women of the Restoration Movement

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Fife 1999, p. 212.

- ^ Rubel Shelly, I Just Want to Be a Christian, 20th Century Christian, Nashville, TN 1984, ISBN 0-89098-021-7

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Hawley, Monroe E (1976), Redigging the Wells: Seeking Undenominational Christianity, Abilene, TX: Quality, pp. 27–32, ISBN 0-89137-513-9

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v McAlister, Lester G; Tucker, William E (1975), Journey in Faith: A History of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), St Louis: Chalice Press, ISBN 978-0-8272-1703-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pp.

- ^ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (2004)

- ^ Melton's Encyclopedia of American Religions (2009)

- ^ Restoration Movement, Kentaurus, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Foster et al. 2004, p. 551, 'Names of the Movement'.

- ^ Foster et al. 2004, p. 755, 'Unity, Christian'.

- ^ Foster et al. 2004, pp. 252–54, 'Creeds and Confessions'.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Allen & Hughes 1988

- ^ The Lutheran Church, Missouri Synod, 'Restoration Movement: History, Beliefs, and Practices', p. 2

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Foster et al. 2004, p. 688, 'Slogans'.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 11.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, pp. 22–3.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, pp. 32–3.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 33.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 78.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Allen & Hughes 1988, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 79.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, pp. 50–6.

- ^ JD Murch, 'Christians Only' (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2004), p. 360

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 65.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 66.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 68.

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, pp. 89–94.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 89.

- ^ Foster et al. 2004, p. 368, 'Great Awakenings'.

- ^ McFadden, Jeff (2006), One Baptism, Lulu, ISBN 978-1-84728-381-8, 248 pp.

- ^ Olbricht, Thomas H, Who Are the Churches of Christ?, CA: Mun, archived from the original on 2012-01-11.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Foster et al. 2004, p. 190, Christian Connection.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on "Stone, Barton Warren"

- ^ Jump up to:a b Dr. Adron Doran, Restoring New Testament Christianity: Featuring Alexander Campbell, Thomas Campbell, Barton W. Stone, and Hall L. Calhoun, 21st Century Christian, 1997

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on "Calvinism"

- ^ Marshall, Robert; Dunlavy, John; M'nemar, Richard; Stone, BW; Thompson, John; Purviance, David (1804), The Last Will and Testament of the Springfield Presbytery, CA: MUN.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Hughes, Richard Thomas; Roberts, RL (2001), The Churches of Christ (2nd ed.), Greenwood, p. 345, ISBN 978-0-313-23312-8

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Davis, M. M. (1915). How the Disciples Began and Grew, A Short History of the Christian Church, Cincinnati: The Standard Publishing Company

- ^ "Philadelphia Confession", Reformed reader.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Rhodes, Ron (2005), The Complete Guide to Christian Denominations, Harvest House, ISBN 0-7369-1289-4

- ^ Allen & Hughes 1988, pp. 106–8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Allen & Hughes 1988, p. 108.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Garrison, Winfred Earnest; DeGroot, Alfred T (1948), The Disciples of Christ, A History, St Louis, MO: The Bethany Press.

- ^ Foster et al. 2004, pp. xxi, xxxvii, 'Stone-Campbell History Over Three Centuries: A Survey and Analysis', 'Introductory Chronology'.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Tristano, Richard M (December 1998), Origins of the Restoration Movement: An Intellectual History (PDF), Glenmary Research Center, ISBN 0-914422-17-0

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Hunt, William C (1910), Religions Bodies: 1906, vol. Part 1, Summary and General Tables, Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census, Government Printing Office.

- ^ Foster et al. 2004, pp. 543–44, "Moore, William Thomas".

- ^ Foster et al. 2004, p. 361, Gospel Advocate.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Missionary Societies, Controversy Over, pp. 534-537

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Louisville Plan, The, pp. 496-497

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on American Christian Missionary Society, pages 24-26

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Conventions, pp. 237-240

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Instrumental Music

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Brewster, Ben (2006), Torn Asunder: The Civil War and the 1906 Division of the Disciples, College Press, ISBN 978-0-89900-951-3, 135 pp.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Foster & Dunnavant 2004, p. 597, 'Pinkerton, Lewis Letig'

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Foster & Dunnavant 2004, p. 77, 'Bible, Authority and Inspiration of the'

- ^ Foster & Dunnavant, p. 576, 'Open Membership'.

- ^ David Lipscomb, 1899, as quoted by Leroy Garrett on page 104 of The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ Reid, DG; Linder, RD; Shelley, BL; Stout, HS (1990), "Churches of Christ (Non-Instrumental)", Dictionary of Christianity in America, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

- ^ Zuber, Glenn (2004). "Temperance", The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement, edited by Douglas A. Foster, Paul Blowers, and D. Newell Williams. Grand Rapids, Erdmans Publishing, 728–729.

- ^ Zuber, Glenn (2002). "Mainline Women Ministers: Women Missionary and Temperance Organizers Become 'Disciples of Christ' Ministers, 1888–1908." In The Stone-Campbell Movement: An International Religious Tradition, ed. Michael Casey and Douglas A. Foster, 292–316.

- ^ Zuber, Glenn (1993). "The Gospel of Temperance: Early Disciple Women Preachers and the WCTU," Discipliana, 53 (47–60).

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Douglas A. Foster, "What really happened in 1906? A trek through history reveals role of Census," The Christian Chronicle, April 2006 (accessed November 20, 2013)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Douglas A. Foster, "1906: The True Story," The Christian Standard, June 25, 2006 (accessed November 20, 2013)

- ^ Cartwright, Colbert S (1987). People of the Chalice, Disciples of Christ in Faith and Practice. St Louis, MO: Chalice Press. ISBN 978-0-8272-2938-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Lipscomb, David

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Samuel S Hill, Charles H Lippy, Charles Reagan Wilson, Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, Mercer University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-86554-758-2 pp. 854

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Matlins, Stuart M; Magida, Arthur J; Magida, J (1999), "6 – Churches of Christ", How to Be a Perfect Stranger: A Guide to Etiquette in Other People's Religious Ceremonies, Wood Lake, ISBN 978-1-896836-28-7, 426 pp.

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, page 206, entry on Church, Doctrine of the

- ^ McAlister & Tucker, (1975). page 421

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Denominationalism

- ^ Jump up to:a b Williams, D Newell (March 27, 2008), "The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ): A Reformed North American Mainstream Moderate Denomination", The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) Consultation on "Becoming a Multicultural and Inclusive Church" (PDF) (presentation), archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011, retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Christian Churches/Churches of Christ

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Ministry

- ^ Jump up to:a b "The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), Year 2000 Report". ARDA. 2000. Retrieved November 26, 2013. Churches were asked for their membership numbers.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Baptism

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Disciple Heritage Fellowship

- ^ Disciple heritage.

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Restructure

- ^ Jump up to:a b Christian Church (Disciples of Christ): Denominational Profile, Association of Religion Data Archives website (accessed November 27, 2013)

- ^ Christian Church (Disciples of Christ): Distribution, Association of Religion Data Archives website (accessed November 27, 2013)

- ^ Christian Church (Disciples of Christ): Map by Number of Adherents, Association of Religion Data Archives website (accessed November 27, 2013)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kragenbrink, Kevin R (2000), "The Modernist/Fundamentalist Controversy and the Emergence of the Independent Christian Churches/Churches of Christ", Restoration Quarterly, 42 (1): 1–17, archived from the original on 2013-11-10.

- ^ "Churches of Christ from the beginning have maintained no formal organization structures larger than the local congregations and no official journals or vehicles declaring sanctioned positions. Consensus views do, however, often emerge through the influence of opinion leaders who express themselves in journals, at lectureships, or at area preacher meetings and other gatherings" page 213, Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b Baxter, Batsell Barrett, Who are the churches of Christ and what do they believe in?, Woodson chapel, archived from the original on 2008-05-02.

- ^ "Churches of Christ adhere to a strict congregationalism that cooperates in various projects overseen by one congregation or organized as parachurch enterprises, but many congregations hold themselves apart from such cooperative projects." Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, page 206, entry on Church, Doctrine of the

- ^ "It is nothing less than phenomenal that the Churches of Christ get so much done without any centralized planning or structure. Everything is ad hoc. Most programs emerge from the inspiration and commitment of a single congregation or even a single person. Worthwhile projects survive and prosper by the voluntary cooperation of other individuals and congregations." Page 449, Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Churches of Christ

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ross, Bobby Jr. "Who are we?". Features. The Christian Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on International Churches of Christ