그리스도의 교회

| 신약전서, 스톤-캠벨 회복 운동 |

| 회중주의자 |

| 41,498 (전세계)11,790 (미국) [1] |

| 전 세계 2,000,000 (대략); [2] 미국 내 1,113,362명 (2020)[3] |

그리스도의 교회들은 성경에 대한 그들의 해석에 기초한 뚜렷한 믿음과 실천을 통해 서로 연관된 자율적인 기독교 회중들이다. 미국과 전 세계의 여러 지부 중 한 곳에서 대표되는 그들은 신약 성경에 묘사 된 초기 기독교 교회의 예를 인용하여 교리와 관행을 위해 성경 본문 만 사용하는 것을 믿습니다. 가장 전형적으로, 그들의 구별되는 신념은 구원을위한 침례의 필요성과 예배에서의 도구의 금지에 대한 믿음입니다. 그들은 자신을 비교파적이라고 생각합니다. [10]

그리스도의 교회는 더 넓은 회복 운동에서 생겨났으며, 19세기 전도 노력은 여러 사람이 신약의 원래 가르침과 실천으로 보았던 것으로 돌아가려고 애쓰면서 전 세계 여러 곳에서 시작되었다. 로버트 샌더먼, 제임스 오켈리, 애브너 존스, 엘리어스 스미스, 토마스 캠벨, 알렉산더 캠벨, 월터 스콧, 바튼 더블유 스톤을 포함한 기독교 지도자들은 미국 회복 운동으로 알려진 최종 현상에 영향을 미치는 유사한 운동의 선구자였다.

복원 이상은 또한 유사했으며 유럽의 초기 복원 노력 (예 : John Glas, Robert Haldane, James Haldane의 노력)과 식민지 미국의 청교도 운동과 다소 관련이 있습니다. 세부 사항은 다소 다르지만, 각 그룹은 종종 서로 독립적이지만 다양한 교단과 전통 신조로부터 독립을 선언하고 신약 교회의 교리와 관행에 대한 개념으로 돌아갈 새로운 시작을 모색 한 같은 생각을 가진 그리스도인들로 구성되었습니다. 그들은 새로운 교회를 세우는 것이 아니라 오히려 "신약의 원래 교회를 본뜬 한 몸으로 모든 그리스도인들의 통일"을 추구했습니다. [11]: 54 "그리스도의 교회", "기독교 교회", "그리스도의 제자들"이라는 이름은 특정 종교 단체의 신념이나 기원을 암시하는 교파적 명명 관습이 아니라 성경에서 발견되는 용어이기 때문에 운동에 의해 채택되었다.

1906 년 미국 종교 인구 조사 이전에는 복원 운동과 관련된 모든 회중이 인구 조사국에 의해 함께보고되었습니다. 1906년까지 공식적으로 뚜렷한 운동으로 인식되지는 않았지만, 그리스도 교회와 기독교 교회의 분리는 수십 년 동안 점진적으로 일어나고 있었다.

회복 운동은 순전히 북미 현상이 아니었고 18 세기에 적극적인 선교 활동이 시작되었습니다. [12] 현재 아프리카, 아시아, 호주, 남미, 중미, 유럽에 그리스도의 교회가 있다.

개요[편집]

현대 그리스도의 교회들은 회복 운동에 역사적 뿌리를 두고 있는데, 이것은 원래의 "교파적" 기독교로의 복귀를 찾기 위해 교파적 노선을 넘어 기독교인들이 수렴하는 것이었다. [13][14]: 108 이 운동에 참여한 참가자들은 서기 1세기 이후 기독교를 정의하게 된 전통적인 공의회와 교파적 위계질서를 인정하기보다는 자신의 교리와 실천을 성경에만 기초하고자 했다.[13][14]: 82, 104, 105 그리스도 교회의 회원들은 예수 오직 하나의 교회만을 세웠고, 그리스도인들 사이의 현재의 분열은 하나님의 뜻을 표현하지 않으며, 그리스도인의 일치를 회복시키는 유일한 기초는 성경이라고 믿습니다. [13] 그들은 다른 형태의 종교적 또는 교파적 신분을 사용하지 않고 단순히 자신을 "기독교인"으로 식별합니다. [15][16][17]: 213 그들은 그리스도께서 세우신 신약 교회를 재창조하고 있다고 믿는다. [18][19][20]: 106

그리스도 교회의 교인들은 19세기 초에 시작된 새로운 교회로 자신을 생각하지 않는다. 오히려, 전체 운동은 서기 33 년 오순절에 원래 설립 된 교회를 현대에 재현하도록 설계되었습니다. 호소의 힘은 그리스도의 원래 교회의 회복에 있습니다.

그리스도의 교회들은 일반적으로 다음과 같은 신학적 믿음과 실천을 공유한다:[13]

- 교단의 감독없이 자율적이고 회중 교회 조직; [21]: 238 [22]: 124

- 공식적인 신조나 비공식적 "교리적 진술" 또는 "신앙의 진술"을 고수하는 것을 거부하고, 대신 교리와 실천을 위해 성경에만 의존한다는 것을 진술하는 것; [20]: 103 [21]: 238, 240 [22]: 123

- 지역 거버넌스[21]: 다수의 남성 장로들에 의한 238 ; [22]: 124 [23]: 47–54

- 동의하는 신자들의 침수로 세례[21]: 238 [22]: 124 죄 사함을 위하여 예수 그리스도의 이름으로 [13][20]: 103 [22]: 124

- 주의 만찬을 매주 지키[22]: 일요일에 124[20]: 107 [21]: 238

- 영국 회중에서는 "빵을 떼는 것"이라는 용어가 일반적으로 사용됩니다.

- 미국 회중에서는 "친교"또는 "몸과 피"라는 용어가 사용됩니다.

- 그리스도의 교회들은 일반적으로 매주 첫째 날에 열린 친교를 베풀며, 포도나무의 빵과 열매를 각 사람의 자기 점검에 참석하는 모든 사람들에게 바친다.

- 카펠라 노래의 실천은 예배의 표준이며,[24] 신약 성경 구절에 근거하여 예배를 위해 노래하도록 가르치며, 악기 음악에 대한 언급은 없습니다 (또한 초대 교회에서 수세기 동안 교회 집회에서 예배를 드리는 것은 카펠라 노래를 연습했습니다). [21]: 240 [22]: 125 (에베소서 5:19)

그들의 역사에 따라, 그리스도의 교회들은 신약이 교리와 교회 구조의 문제를 결정할 때 신앙과 실천의 유일한 규칙이라고 주장합니다. [골로새서 2:14] 그들은 구약전서를 신성하게 영감을 받은 것으로 본다[20]: 103 그리고 역사적으로 정확하지만, 구약의 율법이 그리스도 안에 있는 새 언약 아래 구속력이 있다고 생각하지 않는다(신약전서에서 반복되지 않는 한)(히브리서 8:7-13). [25]: 388 [26]: 23~37 [27]: 65~67 그들은 신약전서가 어떻게 사람이 그리스도인이 될 수 있는지(따라서 그리스도의 보편적 교회의 일부)가 될 수 있는지, 그리고 교회가 어떻게 집합적으로 조직되고 성경적 목적을 수행해야 하는지를 보여 준다고 믿는다. [13]

인구 통계[편집]

2022년에, 그리스도의 교회의 총 회원 수는 1,700,000명에서 2,000,000명 사이로 추정되며,[28][29] 전 세계적으로 40,000개 이상의 개별 회중이 있다. [29] 미국에는 대략 1,087,559명의 회원과 11,776명의 회중이 있다. [29] 전체 미국 회원 수는 1990 년에 약 1.3 백만, 2008 년에 1.3 백만이었다. [30] : 5 그리스도의 교회와 관련된 미국 성인 인구의 비율의 추정치는 0.8 %에서 1.5 %까지 다양합니다. [30]: 5 [31]: 12, 16 약 1,240 회중, 172,000 회원, 주로 아프리카 계 미국인이다; 10,000 명의 회원이있는 240 개의 회중이 스페인어를 사용합니다. [32]: 213 평균 회중 규모는 약 100명이며, 더 큰 회중은 1,000명 이상의 회원을 보고한다. [32]: 213 2000 년에, 그리스도의 교회는 교인의 수에 근거를 둔 미국에서 12번째로 큰 종교 단체이었다, 그러나 회중 수의 4번째로 큰 이었다. [33]

미국 내에서 그리스도의 교회 회원 수는 1980 년부터 2007 년까지 약 12 % 감소했습니다. 고등학교를 졸업한 청년들의 현재 유지율은 약 60%로 보인다. 회원 자격은 미국 회원의 70 %가 열세 개 주에 집중되어 있습니다. 그리스도의 교회는 2,429개 카운티에 존재하여 연합감리교회, 가톨릭교회, 남침례교 협약 및 하나님의 성회에 이어 다섯 번째로 뒤쳐졌지만 카운티당 평균 지지자 수는 약 677명이었다. 이혼율은 6.9 %로 전국 평균보다 훨씬 낮았다. [33]

이름[편집]

"그리스도의 교회"는이 그룹이 사용하는 가장 일반적인 이름입니다. 교단이 아니라는 것에 초점을 맞추면서, 에베소서 1:22,23을 교회가 그리스도의 몸이고 몸이 나뉘어질 수 없다는 언급으로 사용하면서, 회중들은 주로 공동체 교회로, 그리고 이차적으로 그리스도의 교회로 자신을 확인했다. [32]: 219~220 훨씬 더 초기의 전통은 회중을 다른 설명이나 한정자 없이 특정 위치에 있는 "교회"로 식별하는 것이다. [32]: 220 [34]: 136~137 그 이름 뒤에 있는 주된 동기는 성경적 또는 성경적 이름을 사용하려는 소망, 즉 신약전서에 있는 이름을 사용하여 교회를 식별하려는 소망이다. [11][23]: 163, 164 [34][35]: 7~8 신봉자들은 학자들에 의해 캠벨 족속이라고도 불린다.[17] 및 다른 교파들[36] 왜냐하면 그들은 루터교인이나 칼빈주의자들과 비슷한 알렉산더 캠벨의 가르침을 따르는 자들이라고 추정되기 때문이다. 캠벨 자신은 교단이 자신에 의해 시작되었다거나 그가 1826년과 1828년에 기독교 침례교 출판물에서 한 교단의 우두머리였다는 생각을 반박하면서 다음과 같이 말했다: "켄터키의 일부 종교 편집자들은 고대의 질서가 회복되는 것을 보고 싶어 하는 사람들을 '회복자들', '캠벨라이트들'이라고 부른다. 이것은 일부와 잘 어울릴 수 있습니다. 그러나 하나님을 경외하고 그의 명령을 지키는 모든 사람들은 그러한 방법으로 설득하거나 설득하려고 생각하는 사람들의 약점과 어리석음을 불쌍히 여기고 개탄할 것이다."(The Christian Baptist, Vol. IV, 88-89) 그리고 "그것은 견해, 감정 및 욕망이 모두 종파적인 사람들, 즉 기독교를 ISM 이외의 다른 관점에서 생각할 수 없는 사람들에 의해 발명되고 채택된 비난의 별명이다" (기독교 침례교 , Vol. V, 270). 그는 또한 1820년까지 침례교 교단과 연관이 있었다. "캠벨라이트"라는 용어는 일반적으로 그리스도의 교회 회원들에게 불쾌감을 주는데, 왜냐하면 회원들은 그리스도 외에는 누구에게도 충성을 주장하지 않으며 성경 본문에 제시된 것만을 가르치기 때문예수니다. [37]

알렉산더 캠벨 (Alexander Campbell)은 그 목표가 "성경의 모든 것을 성경 이름으로 부르는 것"이라고 말했다. [인용 필요] 이것은 회복주의 운동의 초기 슬로건이되었습니다. [38]: 688 이 회중들은 일반적으로 교회를 특정한 사람(그리스도 이외의) 또는 특정한 교리나 신학적 관점(예를 들어, 루터교, 웨슬리안, 개혁주의)과 연관시키는 이름들을 피한다. [11][16] 그들은 그리스도께서 오직 하나의 교회만을 세우셨으며, 교단 이름을 사용하는 것이 그리스도인들 사이의 분열을 조장하는 데 도움이 된다고 믿는다. [23]: 23, 24 [34][39][40][41][42] 토마스 캠벨은 그의 선언과 연설에서 일치의 이상을 표현했다: "지상에 있는 예수 그리스도의 교회는 본질적으로, 의도적으로, 그리고 헌법적으로 하나이다." [38]: 688 이 말씀은 본질적으로 요한복음 17:21, 23에 나오는 예수 그리스도의 말씀을 반영합니다.

신약 성경에서 "하나님의 교회", "주님의 교회", "그리스도의 교회", "맏아들의 교회", "살아 계신 하나님의 교회", "하나님의 집", "하나님의 백성"[34][43]과 같은 다른 용어들이 사용되면서 파생되지만, 하나님의 교회와 같이 성경으로 인정되는 용어들은 그러한 명칭을 사용하는 다른 집단과의 혼동이나 동일시를 방지하기 위해 피한다. [11][34][44] 실용적인 문제로서, 공통된 용어의 사용은 개별 그리스도인들이 경전과 비슷한 접근 방식을 가진 회중을 찾도록 돕는 방법으로 여겨진다. [34][45] 회원들은 경전 이름이 "교파적" 또는 "종파적" 방식으로 사용될 수 있다는 것을 이해한다. [11]: 31 [34]: 83–94, 134–136 [43] "그리스도의 교회"라는 용어를 독점적으로 사용하는 것은 교단을 식별하는 것으로 비판을 받아왔다. [11]: 31 [34]: 83~94, 134~136 [43] 많은 회중과 개인은 "그리스도의 교회"와 "그리스도의 교회"라는 문구에서 "교회"라는 단어를 대문자로 사용하지 않는다. [46]: 382 [47] 이것은 신약전서에서 "그리스도의 교회"라는 용어가 묘사적인 문구로 사용되었다는 이해에 기초하며, 이는 교회가 적절한 이름이라기보다는 그리스도께 속한다는 것을 가리킨다. [34]: 91

교회 조직[편집]

회중 자율성과 지도력[편집]

교회 정부는 교단이 아니라 회중입니다. 그리스도의 교회들은 의도적으로 지방 교회 수준 이상의 중앙 본부, 공의회 또는 기타 조직 구조를 가지고 있지 않다. [17]: 214 [20]: 103 [21]: 238 [22]: 124 [48] 오히려, 독립 회중은 각 회중이 다양한 봉사 수단과 다른 회중과의 교제에 참여하는 네트워크이다(후원 교회(그리스도의 교회) 참조). [13][22]: 124 [49][50] 그리스도의 교회들은 성경적 회복 원리들에 대한 공동의 헌신으로 연결되어 있다. [13][20]: 다른 교회 회중과 함께 참여하지 않고 외부 원인(선교 사업, 고아원, 성서 대학 등)을 지원하기 위해 자원을 모으는 것을 거부하는 106 개의 회중을 "비제도적"이라고 부르기도 한다.

회중은 일반적으로 집사에 의해 다양한 사업의 집행에 도움을받는 다수의 장로들에 의해 감독됩니다. [13][22]: 124 [23]: 47, 54~55 장로들은 일반적으로 회중의 영적 복지를 책임지는 것으로 보이지만, 집사들은 교회의 비영적 필요에 대한 책임으로 여겨진다. [51]: 531 집사들은 장로들의 감독 하에 봉사하며, 종종 특정 사역에 배정된다. [51]: 531 집사로서 성공적인 봉사는 종종 장로직을 위한 준비로 여겨진다. [51]: 531 장로와 집사는 디모데전서 3장과 디도서 1장에 있는 자격에 근거하여 회중이 임명하는데, 여기에는 그 사람이 남성이어야 한다는 것을 포함한다(여성 장로와 집사는 성경에서 찾을 수 없기 때문에 인정되지 않는다). [23]: 53, 48~52 [52][53]: 323, 335 회중은 목사를 감독하고 가르치고, "통치" 기능을 수행할 수 있도록 경전에 대해 충분히 잘 이해하고 있는 장로들을 찾는다. [54]: 298 이러한 자격을 충족하는 기꺼이 하는 사람들이 없을 때, 회중은 때때로 회중의 남자들에 의해 감독된다. [55]

초기 회복 운동은 "위치한 설교자"가 아닌 순회 설교자의 전통을 가지고 있었지만, 20 세기 동안 장기적이고 공식적으로 훈련 된 회중 목사가 그리스도의 교회 사이에서 표준이되었습니다. [51]: 532 목회자들은 장로들의 감독 하에 봉사하는 것으로 이해된다[54]: 298 그리고 장로로서 자격이 있을 수도 있고 그렇지 않을 수도 있다. 장기 전문 목사의 존재는 때때로 "중요한 사실상의 사역 권위"를 창출하고 목사와 장로 간의 갈등을 초래했지만, 장로직은 "회중의 궁극적 인 권위의 자리"로 남아 있습니다. [51]: 531 그러나 "위치한 목사" 개념에 반대하는 그리스도의 교회들 중 작은 부분이 있다(아래 참조).

그리스도의 교회는 모든 신자들의 신권을 지킨다. [56] 그들을 "성직자"로 식별하는 설교자나 목사에게는 특별한 칭호가 사용되지 않는다. [20]: 106 [26]: 112~113 많은 목회자들이 종교에 대한 학부 또는 대학원 교육, 또는 대학이 아닌 설교 학교를 통한 설교에 대한 구체적인 훈련을 받고 있다. [32]: 215 [51]: 531 [57]: 607 [58]: 672, 673 그리스도의 교회들은 "성직자"와 "평신도" 사이에는 구별이 없으며, 모든 회원은 교회의 일을 성취하는 데 있어서 은사와 역할을 가지고 있음을 강조한다. [59]: 38–40

그리스도의 교회 내의 변형[편집]

그리스도의 교회 안에는 식별 가능한 주류가 있지만, 교제 안에는 상당한 차이가 있습니다. [17]: 212 [32]: 213 [60]: 31, 32 [61]: 4 [62]: 1, 2 신약 교회를 회복하기 위해 취해진 접근법은 교회 조직, 예배의 형태, 교회가 어떻게 기능해야 하는가와 같은 "방법과 절차"에 초점을 맞추었다. 결과적으로, 그리스도의 교회들 사이의 대부분의 분열은 "방법론적" 논쟁의 결과였다. 이것들은 "원시 교회의 형태와 구조를 회복"한다는 목표를 취하는 진지함 때문에이 운동의 회원들에게 의미가 있습니다. [17]: 212

회중의 세 분기와 회원의 87 %는 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과 사전에서 "주류"로 묘사되어 실천과 신학에 대한 일반적인 합의를 공유합니다. [32]: 213

회중은 찬송가에서 카펠라 음악 (아마도 피치 파이프에서 피치 된 것)이지만 시간 서명을 움직이는 유능한 노래 지도자가 지시하는 것은 특히 그리스도의 교회의 특징입니다. [21]: 240 [63]: 417 [64] "공식적인" 주간 소집 중에 손을 박수하거나 악기를 사용하는 회중은 거의 없다.

나머지 회중들은 네 가지 범주로 분류될 수 있는데, 이는 일반적으로 신학적 관점보다는 특정 관행에서의 주류 합의와 다르며, 평균적으로 더 작은 회중을 갖는 경향이 있다. [32]: 213

이 네 가지 범주 중 가장 큰 것은 그리스도의 "비 제도적"교회입니다. 이 그룹은 고아원과 성서 대학과 같은 기관에 대한 회중 지원에 반대하는 것으로 유명합니다. 마찬가지로, 비 제도적 인 회중은 또한 비 교회 활동 (예 : 친교 만찬 또는 레크리에이션)을위한 교회 시설의 사용에 반대합니다. 따라서 그들은 "펠로우십 홀", 체육관 및 유사한 구조물의 건설에 반대합니다. 두 경우 모두 반대는 제도의 지원과 비 교회 활동이 지역 교회의 적절한 기능이 아니라는 믿음에 근거합니다. 약 2,055 개의 회중이이 범주에 속합니다. [32]: 213 [65]

The remaining three groups, whose congregations are generally considerably smaller than those of the mainstream or non-institutional groups, also oppose institutional support as well as "fellowship halls" and similar structures (for the same reasons as the non-institutional groups), but differ by other beliefs and practices (the groups often overlap, but in all cases hold to more conservative views than even the non-institutional groups):[32]: 213

- One group opposes separate "Sunday School" classes for children or gender-separated (the groups thus meet only as a whole assembly in one area); this group consists of approximately 1,100 congregations. The no Sunday School group generally overlaps with the "one-cup" group and may overlap with the "mutual edification" group as defined below.

- Another group opposes the use of multiple communion cups (the term "one-cup" is often used, sometimes pejoratively as "one-cuppers", to describe this group); there are approximately 550 congregations in this group. Congregations in this group differ as to whether "the wine" should be fermented or unfermented, whether the cup can be refilled if during the service it runs dry (or even if it is accidentally spilled), and whether "the bread" can be broken ahead of time or must be broken by the individual participant during Lord's Supper time.

- The last and smallest group "emphasize[s] mutual edification by various leaders in the churches and oppose[s] one person doing most of the preaching" (the term "mutual edification" is often used to describe this group); there are approximately 130 congregations in this grouping.

Beliefs[edit]

Churches of Christ seek to practice the principle of the Bible being the only source to find doctrine (known elsewhere as sola scriptura).[22]: 123 [66] The Bible is generally regarded as inspired and inerrant.[22]: 123 Churches of Christ generally see the Bible as historically accurate and literal, unless scriptural context obviously indicates otherwise. Regarding church practices, worship, and doctrine, there is great liberty from congregation to congregation in interpreting what is biblically permissible, as congregations are not controlled by a denominational hierarchy.[67] Their approach to the Bible is driven by the "assumption that the Bible is sufficiently plain and simple to render its message obvious to any sincere believer".[17]: 212 Related to this is an assumption that the Bible provides an understandable "blueprint" or "constitution" for the church.[17]: 213

If it's not in the Bible, then these folks aren't going to do it.

Historically, three hermeneutic approaches have been used among Churches of Christ.[25]: 387 [68]

- Analysis of commands, examples, and necessary inferences;

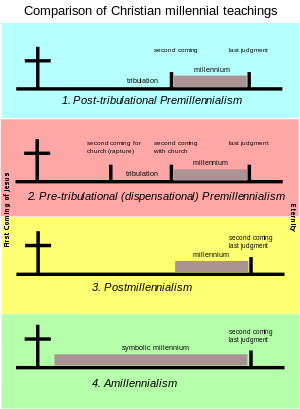

- Dispensational analysis distinguishing between Patriarchal, Mosaic and Christian dispensations (however, Churches of Christ are amillennial and generally hold preterist views); and

- Grammatico-historical analysis.

The relative importance given to each of these three strategies has varied over time and between different contexts.[68] The general impression in the current Churches of Christ is that the group's hermeneutics are entirely based on the command, example, inference approach.[68] In practice, interpretation has been deductive, and heavily influenced by the group's central commitment to ecclesiology and soteriology.[68] Inductive reasoning has been used as well, as when all of the conversion accounts from the book of Acts are collated and analyzed to determine the steps necessary for salvation.[68] One student of the movement summarized the traditional approach this way: "In most of their theologizing, however, my impression is that spokespersons in the Churches of Christ reason from Scripture in a deductive manner, arguing from one premise or hypothesis to another so as to arrive at a conclusion. In this regard the approach is much like that of science which, in practice moves deductively from one hypothesis to another, rather than in a Baconian inductive manner."[68] In recent years, changes in the degree of emphasis placed on ecclesiology and soteriology has spurred a reexamination of the traditional hermeneutics among some associated with the Churches of Christ.[68]

A debate arose during the 1980s over the use of the command, example, necessary inference model for identifying the "essentials" of the New Testament faith. Some argued that it fostered legalism, and advocated instead a hermeneutic based on the character of God, Christ and the Holy Spirit. Traditionalists urged the rejection of this "new hermeneutic".[69] Use of this tripartite formula has declined as congregations have shifted to an increased "focus on 'spiritual' issues like discipleship, servanthood, family and praise".[25]: 388 Relatively greater emphasis has been given to Old Testament studies in congregational Bible classes and at affiliated colleges in recent decades. While it is still not seen as authoritative for Christian worship, church organization, or regulating the Christian's life, some have argued that it is theologically authoritative.[25]: 388

Many scholars associated with the Churches of Christ embrace the methods of modern Biblical criticism but not the associated anti-supernaturalistic views. More generally, the classical grammatico-historical method is prevalent, which provides a basis for some openness to alternative approaches to understanding the scriptures.[25]: 389

Doctrine of salvation (soteriology)[edit]

Churches of Christ are strongly anti-Lutheran and anti-Calvinist in their understanding of salvation and generally present conversion as "obedience to the proclaimed facts of the gospel rather than as the result of an emotional, Spirit-initiated conversion".[32]: 215 Churches of Christ hold the view that humans of accountable age are lost because they have committed sins.[22]: 124 These lost souls can be redeemed because Jesus Christ, the Son of God, offered himself as the atoning sacrifice.[22]: 124 Children too young to understand right from wrong and make a conscious choice between the two are believed to be innocent of sin.[20]: 107 [22]: 124 There is no set age for this to occur; it is only when the child learns the difference between right and wrong that they are accountable (James 4:17). Congregations differ in their interpretation of the age of accountability.[20]: 107

Churches of Christ generally teach that the process of salvation involves the following steps:[13]

- One must be properly taught, and hear (Romans 10:14–17);

- One must believe or have faith (Hebrews 11:6, Mark 16:16);

- One must repent, which means turning from one's former lifestyle and choosing God's ways (Acts 17:30);

- One must confess belief that Jesus is the son of God (Acts 8:36–37);

- One must be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ (Acts 2:38); and

- One must live faithfully as a Christian (1 Peter 2:9).

Beginning in the 1960s, many preachers began placing more emphasis on the role of grace in salvation, instead of focusing exclusively on implementing all of the New Testament commands and examples.[61]: 152, 153 This was not an entirely new approach, as others had actively "affirmed a theology of free and unmerited grace", but it did represent a change of emphasis with grace becoming "a theme that would increasingly define this tradition".[61]: 153

Baptism[edit]

Baptism has been recognized as the important initiatory rite throughout the history of the Christian Church,[70]: 11 but Christian groups differ over the manner and time in which baptism is administered,[70]: 11 the meaning and significance of baptism,[70]: 11 its role in salvation,[70]: 12 and who is a candidate for baptism.[70]: 12

Baptism in Churches of Christ is performed only by bodily immersion,[20]: 107 [22]: 124 based on the Koine Greek verb βαπτίζω (baptizō) which is understood to mean to dip, immerse, submerge or plunge.[13][23]: 313–314 [26]: 45–46 [70]: 139 [71]: 22 Immersion is seen as more closely conforming to the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus than other modes of baptism.[13][23]: 314–316 [70]: 140 Churches of Christ argue that historically immersion was the mode used in the first century, and that pouring and sprinkling emerged later.[70]: 140 Over time these secondary modes came to replace immersion, in the State Churches of Europe.[70]: 140 Only those mentally capable of belief and repentance are baptized (e.g., infant baptism is not practiced).[13][22]: 124 [23]: 318–319 [53]: 195

Churches of Christ have historically had the most conservative position on baptism among the various branches of the Restoration Movement, understanding that repentance and baptism by immersion are necessary parts of conversion.[72]: 61 The most significant disagreements concerned the extent to which a correct understanding of the role of baptism is necessary for its validity.[72]: 61 David Lipscomb argued that if a believer was baptized out of a desire to obey God, the baptism was valid, even if the individual did not fully understand the role baptism plays in salvation.[72]: 61 Austin McGary argued that to be valid, the convert must also understand that baptism is for the forgiveness of sins.[72]: 62 McGary's view became the prevailing one in the early 20th century, but the approach advocated by Lipscomb never totally disappeared.[72]: 62 More recently, the rise of the International Churches of Christ, who "reimmersed some who came into their fellowship, even those previously immersed 'for remission of sins' in a Church of Christ," has caused some to reexamine the question of rebaptism.[72]: 66

Churches of Christ consistently teach that in baptism a believer surrenders his life in faith and obedience to God, and that God "by the merits of Christ's blood, cleanses one from sin and truly changes the state of the person from an alien to a citizen of God's kingdom. Baptism is not a human work; it is the place where God does the work that only God can do."[72]: 66 The term "alien" is used in reference to sinners as in Eph 2:12. Baptism is a passive act of faith rather than a meritorious work; it "is a confession that a person has nothing to offer God".[73]: 112 While Churches of Christ do not describe baptism as a "sacrament", their view of it can legitimately be described as "sacramental".[71]: 186 [72]: 66 They see the power of baptism coming from God, who uses baptism as a vehicle, rather than from the water or the act itself,[71]: 186 and understand baptism to be an integral part of the conversion process, rather than as only a symbol of conversion.[71]: 184 A recent trend is to emphasize the transformational aspect of baptism: instead of describing it as nothing more than a legal requirement or sign of something that happened in the past, it is seen as "the event that places the believer 'into Christ' where God does the ongoing work of transformation".[72]: 66 There is a minority that downplays the importance of baptism in order to avoid sectarianism, but the broader trend is to "reexamine the richness of the Biblical teaching of baptism and to reinforce its central and essential place in Christianity".[72]: 66

Because of the belief that baptism is a necessary part of salvation, some Baptists hold that the Churches of Christ endorse the doctrine of baptismal regeneration.[74] However members of the Churches of Christ reject this, arguing that since faith and repentance are necessary, and that the cleansing of sins is by the blood of Christ through the grace of God, baptism is not an inherently redeeming ritual.[70]: 133 [74][75]: 630, 631 One author describes the relationship between faith and baptism this way, "Faith is the reason why a person is a child of God; baptism is the time at which one is incorporated into Christ and so becomes a child of God" (italics are in the source).[53]: 170 Baptism is understood as a confessional expression of faith and repentance,[53]: 179–182 rather than a "work" that earns salvation.[53]: 170

A cappella worship[edit]

The Churches of Christ generally combine 1) the lack of any historical evidence that the early church used musical instruments in worship[11]: 47 [23]: 237–238 [63]: 415 and 2) the lack of scriptural support in the New Testament authorizing the use of instruments in worship service[13][23]: 244–246 to decide that instruments should not be used today in worship. The term a cappella comes from the Italian "as the church", "as chapel", or "as the choir". As such, Churches of Christ have typically practiced a cappella music in worship services.[13][21]: 240 [22]: 124

However, not all Churches of Christ abstain from instruments. The use of musical instruments in worship was a divisive topic within the Stone-Campbell Movement from its earliest years, when some adherents opposed the practice on traditional grounds, while others may have relied on a cappella simply because they lacked access to musical instruments. Alexander Campbell opposed the use of instruments in worship. As early as 1855, some Restoration Movement churches were using organs or pianos, ultimately leading the Churches of Christ to separate from the groups that condoned instrumental music.[76]

Scriptural backing given by members for the practice of a cappella includes:

- Matt 26:30: "And when they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives."[23]: 236

- Rom 15:9: "Therefore I will praise thee among the Gentiles, and sing to thy name";[23]: 236

- Eph 5:18–19: "... be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with all your heart,"[13][23]: 236

- 1 Cor 14:15: "I will sing with the Spirit, and I will sing with the understanding also."[23]: 236

- Col 3:16: "Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly; in all wisdom teaching and admonishing one another with psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts unto God."[23]: 237

- Heb 2:12: "I will declare thy name unto my brethren, in the midst of the church will I sing praise unto thee."[23]: 237

- Heb 13:15: By him therefore let us offer the sacrifice of praise to God continually, that is, the fruit of our lips giving thanks to his name.

There are congregations that permit hand-clapping and a few that use musical instruments in worship.[21]: 240 [63]: 417 [77] Some of the latter describe themselves as a "Church of Christ (Instrumental)".[62]: 667

Other theological tendencies[edit]

Many leaders argue that the Churches of Christ only follow the Bible and have no "theology".[78]: 737 Christian theology as classically understood – the systematic development of the classical doctrinal topics – is relatively recent and rare among this movement.[78]: 737 Because Churches of Christ reject all formalized creeds on the basis that they add to or detract from Scripture, they generally reject most conceptual doctrinal positions out of hand.[79] Churches of Christ do tend to elaborate certain "driving motifs".[78]: 737 These are scripture (hermeneutics), the church (ecclesiology) and the "plan of salvation" (soteriology).[78]: 737 The importance of theology, understood as teaching or "doctrine", has been defended on the basis that an understanding of doctrine is necessary to respond intelligently to questions from others, to promote spiritual health, and to draw the believer closer to God.[73]: 10–11

Churches of Christ avoid the term "theology", preferring instead the term "doctrine": theology is what humans say about the Bible; doctrine is simply what the Bible says.

— Encyclopedia of Religion in the South[17]: 213

Eschatology[edit]

Regarding eschatology (a branch of theology concerned with the final events in the history of the world or of humankind), Churches of Christ are generally amillennial, their originally prevalent postmillennialism (evident in Alexander Campbell's Millennial Harbinger) having dissipated around the era of the First World War. Before then, many leaders were "moderate historical premillennialists" who did not advocate specific historical interpretations. Churches of Christ have moved away from premillennialism as dispensational millennialism has come more to fore in Protestant evangelical circles.[32]: 219 [80] Amillennialism and postmillennialism are the prevailing views today.[22]: 125

Premillennialism was a focus of controversy during the first half of the 20th century.[32]: 219 One of the most influential advocates for that point of view was Robert Henry Boll,[81]: 96–97 [82]: 306 whose eschatological views came to be most singularly opposed by Foy E. Wallace Jr.[83] By the end of the 20th century, however, the divisions caused by the debate over premillennialism were diminishing, and in the 2000 edition of the directory Churches of Christ in the United States, published by Mac Lynn, congregations holding premillennial views were no longer listed separately.[81]: 97 [84]

Work of the Holy Spirit[edit]

During the late 19th century, the prevailing view in the Restoration Movement was that the Holy Spirit currently acts only through the influence of inspired scripture.[85] This rationalist view was associated with Alexander Campbell, who was "greatly affected by what he viewed as the excesses of the emotional camp meetings and revivals of his day".[85] He believed that the Spirit draws people towards salvation but understood the Spirit to do this "in the same way any person moves another—by persuasion with words and ideas". This view came to prevail over that of Barton W. Stone, who believed the Spirit had a more direct role in the life of the Christian.[85] Since the early 20th century, many, but not all, among the Churches of Christ have moved away from this "word-only" theory of the operation of the Holy Spirit.[86] As one scholar of the movement puts it, "[f]or better or worse, those who champion the so-called word-only theory no longer have a hold on the minds of the constituency of Churches of Christ. Though relatively few have adopted outright charismatic and third wave views and remained in the body, apparently the spiritual waves have begun to erode that rational rock."[85] The Churches of Christ hold a cessationist perspective on the gifts of the Spirit.[citation needed][87]

The Trinity[edit]

Thomas Campbell and Barton W. Stone both publicly believed that God is made known in three persons: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Spirit.[88] This traditional trinitarianism, greatly influenced the early church of Christ movement. Although churches of Christ have no formal overarching leadership, the Stone-Campbell belief on the Godhead prevailed throughout churches of Christ during their establishment.[89]

Church history[edit]

The fundamental idea of "restoration" or "Christian Primitivism" is that problems or deficiencies in the church can be corrected by using the primitive church as a "normative model."[90]: 635 The call for restoration is often justified on the basis of a "falling away" that corrupted the original purity of the church.[35][91][92] This falling away is identified with the development of Catholicism and denominationalism.[23]: 56–66, 103–138 [35]: 54–73 [91][92] New Testament verses that discuss future apostasy (2 Thessalonians 2:3) and heresy (e.g., Acts 20:29, 1 Timothy 4:1, 2 Tim 4:l–4:4) are understood to predict this falling away.[91] The logic of "restoration" could imply that the "true" church completely disappeared and thus lead towards exclusivism.[92] Another view of restoration is that the "true Church ... has always existed by grace and not by human engineering" (italics in the original).[93]: 640 In this view the goal is to "help Christians realize the ideal of the church in the New Testament – to restore the church as conceived in the mind of Christ" (italics in the original).[93]: 640 Early Restoration Movement leaders did not believe that the church had ceased to exist, but instead sought to reform and reunite the church.[92][93]: 638 [94][95] A number of congregations' web sites explicitly state that the true church never disappeared.[96] The belief in a general falling away is not seen as inconsistent with the idea that a faithful remnant of the church never entirely disappeared.[23]: 153 [35]: 5 [97]: 41 Some have attempted to trace this remnant through the intervening centuries between the New Testament and the beginning of the Restoration Movement in the early 1800s.[98][99]

One effect of the emphasis placed on the New Testament church is a "sense of historylessness" that sees the intervening history between the 1st century and the modern church as "irrelevant or even abhorrent."[14]: 152 Authors within the brotherhood have recently argued that a greater attention to history can help guide the church through modern-day challenges.[14]: 151–157 [100]: 60–64

Contemporary social and political views[edit]

The churches of Christ maintain a significant proportion of political diversity.[101] According to the Pew Research Center in 2016, 50% of adherents of the churches of Christ identify as Republican or lean Republican, 39% identify as Democratic or lean Democratic and 11% have no preference.[102] Despite this, the Christian Chronicle says that the vast majority of adherents maintain a conservative view on modern social issues. This is evident when the Research Center questioned adherents' political ideology. In the survey, 51% identified as "conservative", 29% identified as "moderate" and just 12% identified as "liberal", with 8% not knowing.[103] In contemporary society, the vast majority of adherents of the churches of Christ view homosexuality as a sin.[104] They cite Leviticus 18:22 and Romans 1:26-27 for their position. Most don't view same-sex attraction as a sin; however, they condemn "acting on same-sex desires".[105] Mainstream and conservative Churches of Christ bar membership for openly LGBT individuals and do not bless or recognize any form of sexual same-sex relationships. Churches oppose same-sex relationships, transitioning to align gender identity, and all forms of what they describe as "sexual deviation", however, they say they don't view it as any worse than fornication or other sins.[106]

History in the United States[edit]

Early Restoration Movement history[edit]

The Restoration Movement originated with the convergence of several independent efforts to go back to apostolic Christianity.[14]: 101 [34]: 27 Two were of particular importance to the development of the movement.[14]: 101–106 [34]: 27 The first, led by Barton W. Stone, began at Cane Ridge, Kentucky and called themselves simply "Christians". The second began in western Pennsylvania and was led by Thomas Campbell and his son, Alexander Campbell; they used the name "Disciples of Christ". Both groups sought to restore the whole Christian church on the pattern set forth in the New Testament, and both believed that creeds kept Christianity divided.[14]: 101–106 [34]: 27–32

The Campbell movement was characterized by a "systematic and rational reconstruction" of the early church, in contrast to the Stone movement which was characterized by radical freedom and lack of dogma.[14]: 106–108 Despite their differences, the two movements agreed on several critical issues.[14]: 108 Both saw restoring the early church as a route to Christian freedom, and both believed that unity among Christians could be achieved by using apostolic Christianity as a model.[14]: 108 The commitment of both movements to restoring the early church and to uniting Christians was enough to motivate a union between many in the two movements.[61]: 8, 9 While emphasizing that the Bible is the only source to seek doctrine, an acceptance of Christians with diverse opinions was the norm in the quest for truth. "In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, love" was an oft-quoted slogan of the period.[107] The Stone and Campbell movements merged in 1832.[34]: 28 [108]: 212 [109]: xxi [110]: xxxvii

The Restoration Movement began during, and was greatly influenced by, the Second Great Awakening.[111]: 368 While the Campbells resisted what they saw as the spiritual manipulation of the camp meetings, the Southern phase of the Awakening "was an important matrix of Barton Stone's reform movement" and shaped the evangelistic techniques used by both Stone and the Campbells.[111]: 368

Christian Churches and Churches of Christ separation[edit]

In 1906, the U.S. Religious Census listed the Christian Churches and the Churches of Christ as separate and distinct groups for the first time.[112]: 251 This was the recognition of a division that had been growing for years under the influence of conservatives such as Daniel Sommer, with reports of the division having been published as early as 1883.[112]: 252 The most visible distinction between the two groups was the rejection of musical instruments in the Churches of Christ. The controversy over musical instruments began in 1860 with the introduction of organs in some churches. More basic were differences in the underlying approach to Biblical interpretation. For the Churches of Christ, any practices not present in accounts of New Testament worship were not permissible in the church, and they could find no New Testament documentation of the use of instrumental music in worship. For the Christian Churches, any practices not expressly forbidden could be considered.[112]: 242–247 Another specific source of controversy was the role of missionary societies, the first of which was the American Christian Missionary Society, formed in October 1849.[113][114] While there was no disagreement over the need for evangelism, many believed that missionary societies were not authorized by scripture and would compromise the autonomy of local congregations.[113] This disagreement became another important factor leading to the separation of the Churches of Christ from the Christian Church.[113] Cultural factors arising from the American Civil War also contributed to the division.[115]

Nothing in life has given me more pain in heart than the separation from those I have heretofore worked with and loved

— David Lipscomb, 1899[116]

In 1968, at the International Convention of Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ), those Christian Churches that favored a denominational structure, wished to be more ecumenical, and also accepted more of the modern liberal theology of various denominations, adopted a new "provisional design" for their work together, becoming the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).[46]: 495 Those congregations that chose not to be associated with the new denominational organization continued as undenominational Christian churches and churches of Christ, completing a separation that had begun decades before.[46]: 407–409 The instrumental Christian Churches and Churches of Christ in some cases have both organizational and hermeneutical differences with the Churches of Christ discussed in this article.[17]: 186 For example, they have a loosely organized convention and view scriptural silence on an issue more permissively,[17]: 186 but they are more closely related to the Churches of Christ in their theology and ecclesiology than they are with the Disciples of Christ denomination.[17]: 186 Some see divisions in the movement as the result of the tension between the goals of restoration and ecumenism, with the a cappella Churches of Christ and Christian churches and churches of Christ resolving the tension by stressing Bible authority, while the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) resolved the tension by stressing ecumenism.[17]: 210 [46]: 383

Race relations[edit]

Early Restoration Movement leaders varied in their views of slavery, reflecting the range of positions common in the Pre-Civil-War U.S.[117]: 619 Barton W. Stone was a strong opponent of slavery, arguing that there was no Biblical justification for the form of slavery then being practiced in the United States and calling for immediate emancipation.[117]: 619 Alexander Campbell represented a more "Jeffersonian" opposition to slavery, writing of it as more of a political problem than as a religious or moral one.[117]: 619 Having seen Methodists and Baptists divide over the issue of slavery, Campbell argued that scripture regulated slavery rather than prohibited it, and that abolition should not be allowed to become an issue over which Christians would break fellowship with each other.[117]: 619 Like the country as a whole, the assumption of white racial superiority was almost universal among those on all sides of the issue, and it was common for congregations to have separate seating for black members.[117]: 619

After the Civil War, black Christians who had been worshiping in mixed-race Restoration Movement congregations formed their own congregations.[117]: 619 White members of Restoration Movement congregations shared many of the racial prejudices of the times.[117]: 620 Among the Churches of Christ, Marshall Keeble became a prominent African-American evangelist. He estimated that by January 1919 he had "traveled 23,052 miles, preached 1,161 sermons, and baptized 457 converts".[117]: 620

To object to any child of God participating in the service on account of his race, social or civil state, his color or race, is to object to Jesus Christ and to cast him from our association. It is a fearful thing to do. I have never attended a church that negroes did not attend.

— David Lipscomb, 1907[118]

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s the Churches of Christ struggled with changing racial attitudes.[117]: 621 Some leaders, such as Foy E. Wallace Jr., and George S. Benson of Harding University railed against racial integration, saying that racial segregation was the Divine Order.[119][120] Schools and colleges associated with the movement were at the center of the debate.[117]: 621 N.B. Hardeman, the president of Freed-Hardeman, was adamant that the black and white races should not mingle, and refused to shake hands with black Christians.[120] Abilene Christian College first admitted black undergraduate students in 1962 (graduate students had been admitted in 1961).[117]: 621 Desegregation of other campuses followed.[117]: 621 [121]

Efforts to address racism continued through the following decades.[117]: 622 A national meeting of prominent leaders from the Churches of Christ was held in June 1968.[117]: 622 Thirty-two participants signed a set of proposals intended to address discrimination in local congregations, church affiliated activities and the lives of individual Christians.[117]: 622 An important symbolic step was taken in 1999 when the president of Abilene Christian University "confessed the sin of racism in the school's past segregationist policies" and asked black Christians for forgiveness during a lectureship at Southwestern Christian College, a historically black school affiliated with the Churches of Christ.[117]: 622 [122]: 695

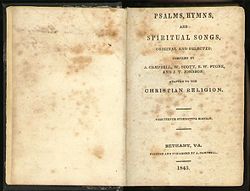

Music[edit]

The tradition of a capella congregational singing in the Churches of Christ is deep set and the rich history of the style stimulated the creation of many hymns in the early 20th century. Notable Churches of Christ hymn writers have included Albert Brumley ("I'll Fly Away") and Tillit S. Teddlie ("Worthy Art Thou"). More traditional Church of Christ hymns commonly are in the style of gospel hymnody. The hymnal Great Songs of the Church, which was first published in 1921 and has had many subsequent editions, is widely used.[76]

While the more conservative and traditional Churches of Christ do not use instruments, since the early 2000s about 20 in the U.S., typically larger congregations, have introduced instruments in place of a strictly a cappella style.[123][124]

Institutional controversy[edit]

After World War II, Churches of Christ began sending ministers and humanitarian relief to war-torn Europe and Asia.

Though there was agreement that separate para-church "missionary societies" could not be established (on the belief that such work could only be performed through local congregations), a doctrinal conflict ensued about how this work was to be done. Eventually, the funding and control of outreach programs in the United States such as homes for orphans, nursing homes, mission work, setting up new congregations, Bible colleges or seminaries, and large-scale radio and television programs became part of the controversy.

Congregations which supported and participated in pooling funds for these institutional activities are said to be "sponsoring church" congregations. Congregations which have traditionally opposed these organized sponsorship activities are said to be "non-institutional" congregations. The institutional controversy resulted in the largest division among Churches of Christ in the 20th century.[125]

Separation of the International Churches of Christ[edit]

The International Churches of Christ had their roots in a "discipling" movement that arose among the mainline Churches of Christ during the 1970s.[126]: 418 This discipling movement developed in the campus ministry of Chuck Lucas.[126]: 418

In 1967, Chuck Lucas was minister of the 14th Street Church of Christ in Gainesville, Florida (later renamed the Crossroads Church of Christ). That year he started a new project known as Campus Advance (based on principles borrowed from the Campus Crusade and the Shepherding Movement). Centered on the University of Florida, the program called for a strong evangelical outreach and an intimate religious atmosphere in the form of soul talks and prayer partners. Soul talks were held in student residences and involved prayer and sharing overseen by a leader who delegated authority over group members. Prayer partners referred to the practice of pairing a new Christian with an older guide for personal assistance and direction. Both procedures led to "in-depth involvement of each member in one another's lives", and critics accused Lucas of fostering cultism.[127]

The Crossroads Movement later spread into some other Churches of Christ. One of Lucas' converts, Kip McKean, moved to the Boston area in 1979 and began working with "would-be disciples" in the Lexington Church of Christ.[126]: 418 He asked them to "redefine their commitment to Christ," and introduced the use of discipling partners. The congregation grew rapidly, and was renamed the Boston Church of Christ.[126]: 418 In the early 1980s, the focus of the movement moved to Boston, Massachusetts where Kip McKean and the Boston Church of Christ became prominently associated with the trend.[126]: 418 [127]: 133, 134 With the national leadership located in Boston, during the 1980s it commonly became known as the "Boston movement".[126]: 418 [127]: 133, 134 A formal break was made from the mainline Churches of Christ in 1993 with the organization of the International Churches of Christ.[126]: 418 This new designation formalized a division that was already in existence between those involved with the Crossroads/Boston Movement and "mainline" Churches of Christ.[46]: 442 [126]: 418, 419 Other names that have been used for this movement include the "Crossroads movement," "Multiplying Ministries," the "Discipling Movement" and the "Boston Church of Christ".[127]: 133

Kip McKean resigned as the "World Mission Evangelist" in November 2002.[126]: 419 Some ICoC leaders began "tentative efforts" at reconciliation with the Churches of Christ during the Abilene Christian University Lectureship in February 2004.[126]: 419

Restoration Movement timeline[edit]

|

↓The American Christian Missionary Society (ACMS)

│

1800

│

1820

│

1840

│

1860

│

1880

│

1900

│

1920

│

1940

│

1960

│

1980

│

2000

│

2020

|

Churches of Christ outside the United States[edit]

Most members of the Churches of Christ live outside the United States. Although there is no reliable counting system, it is anecdotally believed there may be more than 1,000,000 members of the Churches of Christ in Africa, approximately 1,000,000 in India, and 50,000 in Central and South America. Total worldwide membership is over 3,000,000, with approximately 1,000,000 in the U.S.[32]: 212

Africa[edit]

Although there is no reliable counting system, it is anecdotally believed to be 1,000,000 or more members of the Churches of Christ in Africa.[32]: 212 The total number of congregations is approximately 14,000.[128]: 7 The most significant concentrations are in Nigeria, Malawi, Ghana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, South Africa and Kenya.[128]: 7

Asia[edit]

Estimates are that there are 2,000 or more Restoration Movement congregations in India,[129]: 37, 38 with a membership of approximately 1,000,000.[32]: 212 More than 100 congregations exist in the Philippines.[129]: 38 Growth in other Asian countries has been smaller but is still significant.[129]: 38

Australia[edit]

Historically, Restoration Movement groups from Great Britain were more influential than those from the United States in the early development of the movement in Australia. Churches of Christ grew up independently in several locations.[130]: 47 While early Churches of Christ in Australia saw creeds as divisive, towards the end of the 19th century they began viewing "summary statements of belief" as useful in tutoring second generation members and converts from other religious groups.[130]: 50 The period from 1875 through 1910 also saw debates over the use of musical instruments in worship, Christian Endeavor Societies and Sunday Schools. Ultimately, all three found general acceptance in the movement.[130]: 51 Currently, the Restoration Movement is not as divided in Australia as it is in the United States.[130]: 53 There have been strong ties with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), but many conservative ministers and congregations associate with the Christian churches and churches of Christ instead.[130]: 53 Others have sought support from non-instrumental Churches of Christ, particularly those who felt that "conference" congregations had "departed from the restoration ideal".[130]: 53

Canada[edit]

A relatively small proportion of total membership comes from Canada. A growing portion of the Canadian demographic is made up of immigrant members of the church. This is partly the result of Canadian demographics as a whole, and partly due to decreased interest amongst late generation Canadians.[131] The largest concentration of active congregations in Canada are in Southern Ontario, with notable congregations gathering in Beamsville, Bramalea, Niagara Falls, Vineland, Toronto (several), and Waterloo. However, many congregations of various sizes (typically under 300 members) meet all across Canada.[132]

Great Britain[edit]

In the early 1800s, Scottish Baptists were influenced by the writings of Alexander Campbell in the Christian Baptist and Millennial Harbinger.[133] A group in Nottingham withdrew from the Scotch Baptist church in 1836 to form a Church of Christ.[133]: 369 James Wallis, a member of that group, founded a magazine named The British Millennial Harbinger in 1837.[133]: 369 In 1842 the first Cooperative Meeting of Churches of Christ in Great Britain was held in Edinburgh.[133]: 369 Approximately 50 congregations were involved, representing a membership of 1,600.[133]: 369 The name "Churches of Christ" was formally adopted at an annual meeting in 1870.[133]: 369 Alexander Campbell influenced the British Restoration Movement indirectly through his writings; he visited Britain for several months in 1847, and "presided at the Second Cooperative Meeting of the British Churches at Chester".[133]: 369 At that time the movement had grown to encompass 80 congregations with a total membership of 2,300.[133]: 369 Annual meetings were held after 1847.[133]: 369

The use of instrumental music in worship was not a source of division among the Churches of Christ in Great Britain before World War I. More significant was the issue of pacifism; a national conference was established in 1916 for congregations that opposed the war.[133]: 371 A conference for "Old Paths" congregations was first held in 1924.[133]: 371 The issues involved included concern that the Christian Association was compromising traditional principles in seeking ecumenical ties with other organizations and a sense that it had abandoned Scripture as "an all-sufficient rule of faith and practice".[133]: 371 Two "Old Paths" congregations withdrew from the Association in 1931; an additional two withdrew in 1934, and nineteen more withdrew between 1943 and 1947.[133]: 371

Membership declined rapidly during and after the First World War.[133]: 372 [134]: 312 The Association of Churches of Christ in Britain disbanded in 1980.[133]: 372 [134]: 312 Most Association congregations (approximately 40) united with the United Reformed Church in 1981.[133]: 372 [134]: 312 In the same year, twenty-four other congregations formed a Fellowship of Churches of Christ.[133]: 372 The Fellowship developed ties with the Christian churches and churches of Christ during the 1980s.[133]: 372 [134]: 312

The Fellowship of Churches of Christ and some Australian and New Zealand Churches advocate a "missional" emphasis with an ideal of "Five Fold Leadership". Many people in more traditional Churches of Christ see these groups as having more in common with Pentecostal churches. The main publishing organs of traditional Churches of Christ in Britain are The Christian Worker magazine and the Scripture Standard magazine. A history of the Association of Churches of Christ, Let Sects and Parties Fall, was written by David M Thompson.[135] Further information can be found in the Historical Survey of Churches of Christ in the British Isles, edited by Joe Nisbet.[136]

South America[edit]

In Brazil there are above 600 congregations and 100,000 members from the Restoration Movement. Most of them were established by Lloyd David Sanders.[137]

See also[edit]

- Christian churches and churches of Christ

- Christianity in the United States

- Christian primitivism

- Churches of Christ (non-institutional)

- Congregationalist polity

- Gospel Broadcasting Network (GBN) – a television network affiliated with the Churches of Christ

- House to House Heart to Heart – a printed outreach affiliated with the Churches of Christ

- List of universities and colleges affiliated with the Churches of Christ

- 예배의 규제 원리

- 후원 교회 (그리스도의 교회)

- 그리스도 교회의 세계 대회

- 세계 선교 워크샵 - 그리스도의 교회와 관련된 선교 학생, 선교사 및 선교 교수들의 연례 모임

Categories

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Church numbers listed by country". ChurchZip. Retrieved December 5, 2014. This is a country-by-country tabulation, based on the enumeration of specific individual church locations and leaders. While it is known to under-represent certain developing countries, it is the largest such enumeration, and improves significantly on earlier broad-based estimates having no supporting detail.

- ^ "How Many churches of Christ Are There?". The churches of Christ. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Royster, Carl H. (June 2020). "Churches of Christ in the United States" (PDF). 21st Century Christian. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Christian Courier. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "About World Video Bible School". WBVS. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "About The Christian Chronicle". The Christian Chronicle. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "What We Believe". Apologetics Press. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Dave (December 31, 2002). "Who Are These People". Apologetics Press. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "Reaching the Lost" (PDF). House to House. Jacksonville church of Christ. July 2019. p. 2. Retrieved March 20, 2020. under the oversight of the elders

- ^ Hughes, Richard Thomas (2001). The Churches of Christ. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-275-97074-1.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Rubel Shelly, I Just Want to Be a Christian, 20th Century Christian, Nashville, Tennessee 1984, ISBN 0-89098-021-7

- ^ In a sense the Restoration Movement began in the United Kingdom before getting traction in America. See, e.g., Robert Haldane's influence in Scotland.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Baxter, Batsell Barrett. "Who are the churches of Christ and what do they believe in?". Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Also available via these links to church-of-christ.org Archived 2014-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, cris.com/~mmcoc (archived June 22, 2006) and scriptureessay.com (archived July 13, 2006).

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j C. Leonard Allen and Richard T. Hughes, "Discovering Our Roots: The Ancestry of the churches of Christ," Abilene Christian University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-89112-006-8

- ^ "예수 그리스도의 교회는 비교파적이다. 그것은 카톨릭도, 유대인도, 개신교도 아닙니다. 그것은 어떤 기관의 '항의'에서 세워진 것이 아니며, '회복'이나 '개혁'의 산물도 아니다. 그것은 사람들의 마음속에서 자란 왕국의 씨(눅 8:11ff)의 산물이다." V. 이 하워드, 그리스도의 교회는 무엇인가? 제4판(개정), 1971, 29쪽

- ^ Jump up to:a b Batsell Barrett Baxter와 Carroll Ellis, 카톨릭, 개신교 또는 유대인, 트랙, 그리스도의 교회 (1960) ASIN : B00073CQPM. 리처드 토마스 휴즈 (Richard Thomas Hughes)가 고대 신앙을 되살리기 : 미국의 그리스도 교회 이야기, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996 (ISBN 0-8028-4086-8, ISBN 978-0-8028-4086-8)에 따르면, 이것은 "틀림없이 그리스도의 교회 또는 그 전통과 관련된 모든 사람들이 출판 한 가장 널리 배포 된 책자"입니다.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l Samuel S. Hill, Charles H. Lippy, Charles Reagan Wilson, Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, Mercer University Press, 2005, (ISBN 0-86554-758-0, ISBN 978-0-86554-758-2 )

- ^ "미주리 주 스프링필드(Springfield)에 있는 사우스사이드 그리스도 교회의 초석에는 '서기 33년 예루살렘에 세워진 그리스도의 교회'라는 문구가 새겨져 있다. 이 건물은 1953 년에 세워졌습니다. ' 이것은 특별한 주장이 아닙니다. 왜냐하면 미국의 많은 지역에 있는 그리스도의 교회 건물에서도 비슷한 표현이 발견될 수 있기 때문이다. 그러한 모퉁잇돌을 사용하는 그리스도인들은 예수 그리스도의 교회가 서기 33년 오순절에 시작되었다고 추론한다. 그러므로 신약에 충실하기 위해서는 이십 세기 교회가 그 기원을 첫 세기까지 추적해야 한다." 로버트 W. 후퍼, 뚜렷한 민족: 20세기 그리스도 교회의 역사, p. 1, 시몬과 슈스터, 1993, ISBN 1-878990-26-8, ISBN 978-1-878990-26-6, 391페이지

- ^ "그리스도의 전통적인 교회들은 특별한 열정으로 회복주의 비전을 추구해 왔습니다. 사실, 그리스도 건물의 많은 교회의 모퉁잇돌에는 '서기 33년 건국'이라고 쓰여 있습니다. " Jill, et al. (2005), "종교 백과사전", p. 212

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k Stuart M. Matlins, Arthur J. Magida, J. Magida, 완벽한 낯선 사람이되는 방법 : 다른 사람들의 종교 의식에서 에티켓에 대한 안내서, Wood Lake Publishing Inc., 1999, ISBN 1-896836-28-3, ISBN 978-1-896836-28-7, 426 페이지, 제 6 장 - 그리스도의 교회

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s 론 로즈, 기독교 교단에 대한 완전한 가이드, 하베스트 하우스 출판사, 2005, ISBN 0-7369-1289-4

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r V. E. 하워드, 그리스도의 교회는 무엇인가? 제4판 (개정판) Central Printers & Publishers, West Monroe, Louisiana, 1971

- ^ 골드버그, 요나. 종말론적 잡초. 남은 자. 2020년 6월 6일에 확인함 – Apple Podcasts를 통해.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 해석학 항목

- ^ Jump up to:a ᄂ c 에드워드 시 워튼, 그리스도의 교회: 신약 교회의 독특한 본질, 복음 옹호자 주식회사, 1997, ISBN 0-89225-464-5

- ^ 데이비드 파르, 우리의 확신의 시작: 새로운 그리스도인들을 위한 일곱 주간의 매일의 교훈, 21세기 기독교, 2000, 80페이지, ISBN 0-89098-374-7

- ^ "그리스도의 교회 - 그들의 역사와 신념에 대해 알아야 할 10 가지". 십일월 1일 (2018 년). 2022년 7월 27일에 확인함.

- ^ Jump up to:a ᄂ c "국가별로 나열된 교회 번호". 처치 지퍼. 2022년 7월 27일에 확인함. 이것은 특정 개별 교회 위치와 지도자의 열거를 기반으로 한 국가별 표입니다. 특정 개발 도상국을 과소 대표하는 것으로 알려져 있지만, 그러한 열거 형이 가장 크며 지원 세부 사항이없는 이전의 광범위한 기반 추정치에서 크게 향상됩니다.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Barry A. Kosmin and Ariela Keysar, American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS 2008) Archived April 7, 2009, at Wayback Machine, Trinity College, March 2009

- ^ "The Religious Composition of the United States," U.S. Religious Landscape Survey: Chapter 1, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, Pew Research Center, 2008년 2월

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, "그리스도의 교회", 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과 사전 : 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8

- ^ Jump up to:a b Flavil Yeakley, 좋은 소식과 나쁜 소식 : 미국 그리스도의 교회에 대한 현실적인 평가 : 2008; 2009 년 3 월 4 일 2009 East Tennessee School of Preaching and Ministry 강의에서 일부 결과를 발표 한 저자의 mp3는 여기에서 사용할 수 있습니다 [영구 죽은 링크] 캠퍼스 사역 유나이티드 웹 사이트에 게시 된 설문 조사 결과 중 일부를 사용하여 2008 CMU 컨퍼런스의 PowerPoint 프리젠 테이션을 여기에서 사용할 수 있습니다.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m 먼로 E. Hawley, 우물 파고 들기 : 교파적 인 기독교 추구, 품질 간행물, 텍사스 주 Abilene, 1976, ISBN 0-89137-512-0 (종이), ISBN 0-89137-513-9 (천)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d J. W. Shepherd, The Church, the Falling Away, and the Restoration, Gospel Advocate Company, Nashville, Tennessee, 1929 (1973년 재인쇄)

- ^ "Campbellism and the Church of Christ" Archived 2015-01-09 at the Wayback Machine Morey 2014.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary는이 용어를 "때로는 공격적"이라고 묘사합니다. 메리엄 웹스터, I. (2003). 메리엄 웹스터의 대학 사전. (열한번째 에드.). Springfield, MA : Merriam-Webster, Inc. "Campbellite"에 대한 항목.

- ^ Jump up to:a b 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, "슬로건", 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과 사전 : 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8,

- ^ 토마스 캠벨, 선언 및 주소, 1809, 온라인 이용 가능

- ^ O. E. Shields, "The Church of Christ," The Word and Work, VOL. XXXIX, No. 9, September 1945.

- ^ M. C. Kurfees, "성경 이름에 의한 성경 것들 – '교회'라는 용어의 일반적이고 지역적인 감각들", 복음 옹호자 (1920년 10월 14일):1104-1105, 부록 II: 기독교인이 되고 싶다는 나의 회복 문서들, 루벨 셸리(Rubel Shelly, 1984)

- ^ J. C. McQuiddy, "The New Testament Church", Gospel Advocate (1920년 11월 11일):1097–1098, 부록 II: 기독교인이 되고 싶다는 회복 문서, 루벨 셸리(Rubel Shelly, 1984)

- ^ Jump up to:a ᄂ c M. C. Kurfees, "성경 이름에 의한 성경 것들 – 교회의 다른 명칭들이 더 고려됨", 복음 옹호자 (1920년 9월 30일):958-959, 부록 II: 기독교인이 되고 싶다는 회복 문서들, 루벨 셸리(Rubel Shelly, 1984)

- ^ 회복 운동 내에서 예배에 악기를 사용하지 않는 회중은 "그리스도의 교회"라는 이름을 거의 독점적으로 사용합니다. 악기를 사용하는 회중은 "기독교 교회"라는 용어를 가장 자주 사용합니다. 먼로 E. 해울리, 우물 파고: 비종파적 기독교 추구, 1976, 89쪽.

- ^ 예를 들어, 옐로우 페이지의 리스팅을 위해.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ Examples of this usage include the Gospel Advocate website Archived February 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine ("Serving the church of Christ since 1855" – accessed October 26, 2008); the Lipscomb University website ("Classes in every area are taught in a faith-informed approach by highly qualified faculty who represent the range of perspectives that exist among churches of Christ." – accessed October 26, 2008); the Freed-Hardeman University website Archived 2008-10-09 at the Wayback Machine ("Freed-Hardeman University is a private institution, associated with churches of Christ, dedicated to moral and spiritual values, academic excellence, and service in a friendly, supportive environment... The university is governed by a self-perpetuating board of trustees who are members of churches of Christ and who hold the institution in trust for its founders, alumni, and supporters." – accessed October 26, 2008); Batsell Barrett Baxter, Who are the churches of Christ and what do they believe in? (Available on-line here Archived 2008-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, here, here Archived 2014-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, here Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine and here Archived 2010-11-30 at the Wayback Machine); Batsell Barrett Baxter and Carroll Ellis, Neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jew, tract, Church of Christ (1960); Monroe E. Hawley, Redigging the Wells: Seeking Undenominational Christianity, Quality Publications, Abilene, Texas, 1976; Rubel Shelly, I Just Want to Be a Christian, 20th Century Christian, Nashville, Tennessee 1984; and V. E. Howard, What Is the Church of Christ? 4th Edition (Revised), 1971; Website of the Frisco church of Christ ("Welcome to the Home page for the Frisco church of Christ in Frisco, Texas." – accessed October 27, 2008); website of the church of Christ Internet Ministries ("The purpose of this Web Site is to unite the churches of Christ in one accord." – accessed October 27, 2008) "The Church of Christ at Woodson Chapel : Welcome!". Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ^ "Churches of Christ from the beginning have maintained no formal organization structures larger than the local congregations and no official journals or vehicles declaring sanctioned positions. Consensus views do, however, often emerge through the influence of opinion leaders who express themselves in journals, at lectureships, or at area preacher meetings and other gatherings" page 213, Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages

- ^ "Churches of Christ adhere to a strict congregationalism that cooperates in various projects overseen by one congregation or organized as parachurch enterprises, but many congregations hold themselves apart from such cooperative projects." Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, page 206, entry on Church, Doctrine of the

- ^ "그리스도의 교회들이 중앙집권화된 계획이나 구조 없이 그렇게 많은 일을 성취하는 것은 경이로운 일일 뿐이다. 모든 것이 임시입니다. 대부분의 프로그램은 한 회중 또는 심지어 한 사람의 영감과 헌신에서 비롯됩니다. 가치있는 프로젝트는 다른 개인과 회중의 자발적인 협력에 의해 생존하고 번영합니다. " 페이지 449, Leroy Garrett, The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 사역 항목

- ^ 에버렛 퍼거슨, "장로들의 권위와 재임", 2008년 5월 16일 웨이백 머신 복원 분기별 문서, Vol. 18 No. 3 (1975): 142–150

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e 에버렛 퍼거슨, 그리스도의 교회: 오늘을 위한 성경적 교회론, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1996, ISBN 0-8028-4189-9, ISBN 978-0-8028-4189-6, 443 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 장로, 장로 입장

- ^ "장로직이 존재하지 않는 경우, 대부분의 회중은 회중의 구성원 또는 다른 경우에는 교회 사람들을 포함 할 수있는 '비즈니스 미팅'시스템을 통해 기능합니다." 페이지 531, 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 사역에 대한 항목

- ^ 로버츠, 프라이스 (1979). 새로운 개종자를 위한 연구. 신시내티 : 표준 출판사. 53~56쪽.

- ^ 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 설교에 대한 항목

- ^ 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 설교 학교 입장

- ^ R. B. Sweet, Now That I'm a Christian, Sweet Publishing, 1948 (revised 2003), ISBN 0-8344-0129-0

- ^ Jeffery S. Stevenson, All People, All Times Rethinking Biblical Authority in Churches of Christ, Xulon Press, 2009, ISBN 1-60791-539-1, ISBN 978-1-60791-539-3

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Richard Thomas Hughes and R. L. Roberts, The Churches of Christ, 2nd Edition, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 0-313-23312-8, ISBN 978-0-313-23312-8, 345 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ralph K. Hawkins, A Heritage in Crisis: Where We've Been, Where We Are, and Where We're Going in the Churches of Christ, University Press of America, 2008, 147 pages, ISBN 0-7618-4080-X, 9780761840800

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Instrumental Music

- ^ Ross, Bobby Jr (January 2007). "Nation's largest Church of Christ adding instrumental service". christianchronicle.org. The Christian Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Ross, Bobby Jr. "Who are we?". Features. The Christian Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 19, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ "그리스도의 교회들 안에 의견 불일치가 있을 때마다, 모든 종교적 문제를 해결하는 데 있어서 '경전에 대한 언급'이 이루어진다. 경전의 선언은 마지막 단어로 간주된다.'" 페이지 240, 카르멘 르네 베리, 교회 선택에 대한 승인되지 않은 안내서, 브라조스 출판사, 2003

- ^ F. LaGard Smith, "The Cultural Church", 20th Century Christian, 1992, 237 pages, ISBN 978-0-89098-131-3 참조

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Thomas H. Olbricht, "Hermeneutics in the Churches of Christ," Archived 2008-09-22 at the Wayback Machine Restoration Quarterly, Vol. 37/No. 1 (1995)

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, page 219

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Tom J. Nettles, Richard L. Pratt, Jr., John H. Armstrong, Robert Kolb, Understanding Four Views on Baptism, Zondervan, 2007, ISBN 0-310-26267-4, ISBN 978-0-310-26267-1, 222 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Rees Bryant, Baptism, Why Wait?: Faith's Response in Conversion, College Press, 1999, ISBN 0-89900-858-5, ISBN 978-0-89900-858-5, 224 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Baptism

- ^ Jump up to:a b Harold Hazelip, Gary Holloway, Randall J. Harris, Mark C. Black, Theology Matters: In Honor of Harold Hazelip: Answers for the Church Today, College Press, 1998, ISBN 0-89900-813-5, ISBN 978-0-89900-813-4, 368 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas A. Foster, "Churches of Christ and Baptism: An Historical and Theological Overview," Archived May 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Restoration Quarterly, Volume 43/Number 2 (2001)

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Regeneration

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wakefield, John C. (January 31, 2014). "Stone-Campbell tradition, the". The Grove Dictionary of American Music, 2nd edition. Grove Music Online. {{cite web}}: Missing or empty |url= (help)

- ^ Ross, Bobby Jr (January 2007). "Nation's largest Church of Christ adding instrumental service". christianchronicle.org. The Christian Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 신학 항목

- ^ "신조는 그리스도의 몸 안에 분열을 일으킨다고 믿기 때문에 거부당한다. 또한 신학적 패러다임(칼빈주의와 알미니안주의와 같은)은 신약만이 교리적 믿음에 대한 적절한 지침이기 때문에 피해야 한다." 론 로즈, 기독교 교단에 대한 완전한 안내서, 하베스트 하우스 출판사, 2005, ISBN 0-7369-1289-4, 페이지 123.

- ^ 세대적 전천년설은 휴거, 이스라엘의 회복, 아마겟돈 및 관련 사상에 중점을 두는 것이 특징입니다.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Boll, Robert Henry

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Eschatology

- ^ Robert E. Hooper, A Distinct People: A History of the Churches in the 20th Century (West Monroe, LA: Howard Publishing, 1994), pp. 131-180 et passim, ISBN 1-878990-26-8.

- ^ 맥 린, 미국 그리스도의 교회 : 그녀의 연방과 영토를 포함, 이십 세기 기독교 서적, 2000, ISBN 0-89098-172-8, ISBN 978-0-89098-172-6, 682 페이지

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d 더글러스 A. 포스터, "이성적인 반석에 대항하는 성령의 물결: 오순절, 카리스마, 셋째 물결 운동이 미국 그리스도 교회에 미치는 영향," Archived 2011-09-27 at Wayback Machine Restoration Quarterly, 45:1, 2003

- ^ 예를 들어, 하비 플로이드, 성령이 나를 위한 것인가?: 오늘날의 교회에서 성령의 의미에 대한 탐구, 20세기 기독교, 1981, ISBN 978-0-89098-446-8, 128페이지

- ^ Olbricht, Thomas H (2004년 1월 1일). "Barton W. Stone과 Walter Scott on the Holy Spirit and Ministry". 《Barton W. Stone》. 리벤. 12 (3) : 1-6 - Google 학자를 통해.

- ^ Carter, Kelly D. (2015년 5월 10일). 스톤 캠벨 운동의 삼위일체: 기독교 신앙의 마음을 회복함. ACU 프레스. ISBN 978-0-89112-681-2.

- ^ W. Stone, Barton (1827년 2월 24일). "서양 기독교 교회의 역사"(PDF). 기독교 메신저. 1 (74) : 9 - 구글 학자를 통해.

- ^ 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, 9780802838988, 854 페이지, 복원에 대한 항목, 역사적 모델

- ^ Jump up to:a ᄂ c Roy B. Ward, "The Restoration Principle": A Critical Analysis," Archived 2013-12-11 at Wayback Machine Restoration Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1965

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Leroy Garrett (편집자), "회복 또는 개혁", 복원 리뷰, 볼륨 22, 번호 4, April 1980

- ^ Jump up to:a ᄂ c 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, 9780802838988, 854 페이지, "회복"에 대한 항목, 운동 내에서의 의미

- ^ Leroy Garrett (편집자), "왜 그리스도의 교회 배타주의가 가야 하는가", 회복 리뷰, 볼륨 26, 번호 8, 1984년 10월

- ^ Leroy Garrett (편집자), "우리가 말한 것 (2)", 복원 리뷰, Volume 34, Number 9, November 1992

- ^ 예를 들어:

- 역사, 제네시 카운티 그리스도 교회 웹 사이트, (액세스 12/04/2013);

- 교회 역사에서 누락 된 장 아카이브 2014-12-05 웨이백 머신, 웨스트 엔드 그리스도 교회 웹 사이트 아카이브 2014-12-05 - 웨이백 머신 (액세스 12/04/2013);

- 그리스도의 교회는 무엇입니까?, 우드브리지 그리스도 교회 웹사이트 (2013년 12월 4일 액세스);

- John Telgren, Some More About Us Archived 2015년 4월 3일 - 웨이백 머신, Leavenworth Church of Christ 웹 사이트 Archived 2015-04-03 at Wayback Machine (access 12/04/2013);

- A History of the Church of Christ!, Glendale Church of Christ 웹사이트 (access 12/04/2013).

- ^ Mack Lyon, Churches of Christ: Who Are They ?, Publishing Designs, Inc., Huntsville, Alabama, 2006

- ^ 한스 고드윈 그림. (1963). 중부 유럽에서 그리스도의 초기 교회의 전통과 역사. H.L. Schug에 의해 번역됨. 회사 재단 출판사. ASIN B0006WF106.

- ^ Keith Sisman, 왕국의 흔적, 제 2 판, "금지 된 책", 2011, ISBN 978-0-9564937-1-2.

- ^ 제프. W. Childers, Douglas A. Foster and Jack R. Reese, The Crux of the Matter, ACU Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89112-036-X

- ^ "미국 종교 단체와 그들의 정치적 성향". 퓨 리서치 센터. 2020년 3월 20일에 확인함.

- ^ bobbyross (2016년 2월 25일). "pews에있는 코끼리 : GOP는 그리스도의 교회의 당입니까?". 기독교 연대기. 2020년 3월 20일에 확인함.

- ^ "그리스도의 교회 회원들 사이의 정치 이데올로기 - 미국의 종교 : 미국 종교 데이터, 인구 통계 및 통계". 퓨 리서치 센터의 종교 및 공공 생활 프로젝트. 2020년 3월 20일에 확인함.

- ^ "동성애와 트랜스젠더주의: 과학은 성경을 지지한다". apologeticspress.org. 2020년 3월 20일에 확인함.

- ^ "동성애에 대한 솔직한 이야기". 기독교 택배. 2020년 3월 20일에 확인함.

- ^ "결혼의 침식". 기독교 택배. 2020년 3월 20일에 확인함.

- ^ 한스 롤만, "In Essentials Unity: The Pre-history of a Restoration Movement Slogan," Restoration Quarterly, Volume 39/Number 3 (1997)

- ^ Garrison, Winfred Earnest and DeGroot, Alfred T. (1948). 그리스도의 제자들, 역사, 세인트루이스, 미주리: 베다니 출판사

- ^ 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회(그리스도의 제자들), 기독교 교회/그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 3세기에 걸친 스톤-캠벨 역사: 조사 및 분석

- ^ 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 입문 연대기

- ^ Jump up to:a b 더글러스 앨런 포스터와 앤서니 L. 던나반트, 스톤 캠벨 운동의 백과사전: 기독교 교회 (그리스도의 제자), 기독교 교회 / 그리스도의 교회, 그리스도의 교회, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 페이지, 위대한 각성에 대한 항목

- ^ Jump up to:a b c McAlister, Lester G. and Tucker, William E. (1975), Journey in Faith: A History of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) – St. Louis, Chalice Press, ISBN 978-0-8272-1703-4

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Missionary Societies, Controversy Over, pp. 534-537

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on American Christian Missionary Society, pages 24-26

- ^ Reid, D. G., Linder, R. D., Shelley, B. L., & Stout, H. S. (1990). Dictionary of Christianity in America. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. Entry on Churches of Christ (Non-Instrumental)

- ^ David Lipscomb, 1899, as quoted by Leroy Garrett on page 104 of The Stone-Campbell Movement: The Story of the American Restoration Movement, College Press, 2002, ISBN 0-89900-909-3, ISBN 978-0-89900-909-4, 573 pages

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Race Relations

- ^ David Lipscomb, Gospel Advocate, 49 (1 August 1907): 488–489.

- ^ Brown, Michael D (June 6, 2012). "Despite school sentiment, Harding's leader said no to integration". Arkansas Times. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "The manner in which the brethren in some quarters are going in for the negro meetings leads one to wonder whether they are trying to make white folks out of the negroes or negroes out of the white folks. The trend of the general mix-up seems to be toward the latter. Reliable reports have come to me of white women, members of the church, becoming so animated over a certain colored preacher as to go up to him after a sermon and shake hands with him holding his hand in both of theirs. That kind of thing will turn the head of most white preachers, and sometimes affect their conduct, and anybody ought to know that it will make fools out of the negroes. For any woman in the church to so far forget her dignity, and lower herself so, just because a negro has learned enough about the gospel to preach it to his race, is pitiable indeed. Her husband should take her in charge unless he has gone crazy, too. In that case somebody ought to take both of them in charge." Foy E. Wallace, Vol. 3, No. 8 March 1941, "Negro Meetings for White People," in the Bible Banner.

- ^ Don Haymes (June 9, 1961). "Abilene Christian College Desegregates its Graduate School". The Christian Chronicle. 18: 1, 6.

- ^ Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Southwestern Christian College

- ^ De Gennaro, Nancy (April 16, 2015). "Local Church of Christ adds Instruments to Worship". Daily News Journal. Murfreesboro. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Hall, Heidi (March 6, 2015). "Church of Christ opens door to musical instruments". USA Today. The Tennessean. Retrieved January 6, 2017. About 20 of 12,000 Church of Christ congregations nationwide offer instrumental music

- ^ Randy Harshbarger, "A history of the institutional controversy among Texas Churches of Christ: 1945 to the present," M.A. thesis, Stephen F. Austin State University, 2007, 149 pages; AAT 1452110

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on International Churches of Christ

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Paden, Russell (July 1995). "The Boston Church of Christ". In Timothy Miller (ed.). America's Alternative Religions. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 133–36. ISBN 978-0-7914-2397-4. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Africa, Missions in

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Asia, Missions in

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Douglas Allen Foster and Anthony L. Dunnavant, The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement: Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-3898-7, ISBN 978-0-8028-3898-8, 854 pages, entry on Australia, The Movement in

- ^ Wayne Turner, "The Strangers Among Us," Gospel Herald, February 2007