Saxon priest, monk and theologian, seminal figure in Protestant Reformation

작센 사제, 승려, 신학자, 개신교 종교개혁의 신학자

|

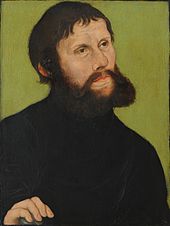

Martin Luther (1529) by Lucas Cranach the Elder루카스 크랜라크 장로의 마틴 루터(1529년) |

|

| 10 November 14831483년 11월 10일 Eisleben, County of Mansfeld, Holy Roman Empire신성로마제국 맨스펠트 군 아이슬레벤 |

|

| 18 February 1546(1546-02-18) (aged 62)1546년 2월 18일(1546-02-18) (62) Eisleben, County of Mansfeld, Holy Roman Empire신성로마제국 맨스펠트 군 아이슬레벤 |

|

| University of Erfurt에르푸르트 대학교 | |

| Katharina von Bora카타리나 폰보라 | |

|

|

| Theological work신학 연구 | |

| Reformation리폼 | |

| Lutheranism루터교 | |

| Five solae, Theology of the Cross, Two kingdoms doctrine.오솔레, 십자가의 신학, 두 왕국 교리. | |

Christianity기독교

| Part of a series on다음에 대한 시리즈 일부 |

|

|

|

|

|

Related topics관련 항목 |

| Christianity portal기독교의 포탈 |

| .mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:"[ "}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:" ]"}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em}.mw-parser-output .infobox .navbar{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .navbox .navbar{display:block;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .navbox-title .navbar{float:left;text-align:left;margin-right:0.5em} |

Lutheranism루터교

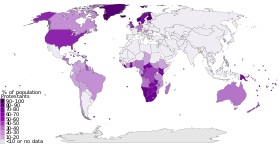

Martin Luther, O.S.A. (/ˈluːθər/;[1] German: [ˈmaʁtiːn ˈlʊtɐ] (

listen); 10 November 1483[2] – 18 February 1546) was a German professor of theology, priest, author, composer, Augustinian monk,[3] and a seminal figure in the Reformation.O.S.A. (/ˈluːθər/;[1] 독일어: [ [maʁtitin ˈlʊtt]

(듣기; 1483년[2] 11월 10일 ~ 1546년 2월 18일)는 독일의 신학 교수, 사제, 작가, 작곡가,[3] 아우구스티누스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스탕스 Luther was ordained to the priesthood in 1507. 루터는 1507년에 사제 서품을 받았다. He came to reject several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church; in particular, he disputed the view on indulgences. 그는 로마 카톨릭 교회의 몇 가지 가르침과 관행을 거부하게 되었고, 특히 면죄부에 대한 관점에 대해 이의를 제기했다. Luther proposed an academic discussion of the practice and efficacy of indulgences in his Ninety-five Theses of 1517. 루터는 1517년 그의 95년 학설에 대한 면죄부의 실천과 효능에 대한 학문적 토론을 제안했다. His refusal to renounce all of his writings at the demand of Pope Leo X in 1520 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521 resulted in his excommunication by the pope and condemnation as an outlaw by the Holy Roman Emperor. 1520년 교황 레오 10세와 1521년 신성로마 황제 찰스 5세의 요구로 자신의 모든 글을 포기하려 하지 않은 것은 교황에 의한 파면과 신성로마 황제에 의한 무법자라는 비난을 초래했다.

Luther taught that salvation and, consequently, eternal life are not earned by good deeds but are received only as the free gift of God's grace through the believer's faith in Jesus Christ as redeemer from sin.루터는 구원과 결과적으로 영원한 삶은 선행에 의해 얻어지는 것이 아니라 오직 죄로부터 구원받은 자로서 예수 그리스도를 믿는 신앙을 통해 하나님의 은총의 자유로운 선물로만 받는다고 가르쳤다. His theology challenged the authority and office of the pope by teaching that the Bible is the only source of divinely revealed knowledge,[4] and opposed sacerdotalism by considering all baptized Christians to be a holy priesthood.[5] 그의 신학은 성경이 신적으로 드러난 지식의 유일한 원천임을 가르침으로써 교황의 권위와 직위에 도전하였고,[4] 세례를 받은 모든 기독교인들을 성직자로 간주하여 천거주의에 반대하였다.[5] Those who identify with these, and all of Luther's wider teachings, are called Lutherans, though Luther insisted on Christian or Evangelical (German: evangelisch) as the only acceptable names for individuals who professed Christ. 루터가 기독교나 복음주의(독일어:복음주의)를 그리스도를 공언한 개인들에게 유일하게 받아들일 수 있는 이름으로 주장했지만, 이것들과 동일시하는 이들, 그리고 루터의 모든 넓은 가르침은 루터교라고 불린다.

His translation of the Bible into the German vernacular (instead of Latin) made it more accessible to the laity, an event that had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture.그가 성경을 독일어(라틴어 대신)로 번역한 것은 교회와 독일 문화 모두에 엄청난 영향을 끼친 사건인 평신도(平道)에 더욱 접근할 수 있게 했다. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language, added several principles to the art of translation,[6] and influenced the writing of an English translation, the Tyndale Bible.[7] 독일어의 표준판 개발을 촉진하고, 번역술에 몇 가지 원리를 추가했으며,[6] 영어 번역문인 틴데일 성경의 집필에 영향을 주었다.[7] His hymns influenced the development of singing in Protestant churches.[8] 그의 찬송가는 개신교 교회에서의 노래 발전에 영향을 미쳤다.[8] His marriage to Katharina von Bora, a former nun, set a model for the practice of clerical marriage, allowing Protestant clergy to marry.[9] 그의 전 수녀인 카타리나 폰 보라와의 결혼은 성직자의 결혼을 허용하면서 성직자의 결혼 관행에 모범이 되었다.[9]

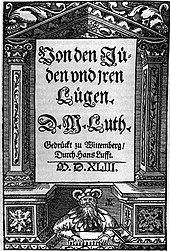

In two of his later works, Luther expressed antagonistic, violent views towards Jews and called for the burnings of their synagogues and their deaths.[10]그의 후기 작품들 중 두 작품에서 루터는 유대인에 대해 적대적이고 폭력적인 견해를 표현했고 유대인들의 회당 불태움과 죽음을 요구했다.[10] His rhetoric was not directed at Jews alone but also towards Roman Catholics, Anabaptists, and nontrinitarian Christians.[11] 그의 미사여구는 유대인만을 겨냥한 것이 아니라 로마 가톨릭 신자, 아나밥티스트, 비trinitive 기독교인을 겨냥한 것이었다.[11] Luther died in 1546 with Pope Leo X's excommunication still in effect. 루터는 1546년 교황 레오 10세의 파문 이후 사망하였다.

Contents내용물

- 1 Early life초년기

- 2 Start of the Reformation개혁의 시작

- 3 Diet of Worms벌레의 식단

- 4 At Wartburg Castle바르트부르크 성에서

- 5 Return to Wittenberg and Peasants' War비텐베르크와 농민 전쟁으로 돌아가기

- 6 Marriage결혼

- 7 Organising the church교회 조직

- 8 Translation of the Bible성경의 번역

- 9 HymnodistHymnodist

- 10 On the soul after death사후 영혼에

- 11 Sacramentarian controversy and the Marburg Colloquy성찬식 논쟁과 마르부르크 콜로키

- 12 Epistemology인식론

- 13 On Islam이슬람에 관하여

- 14 Antinomian controversy안티노미아 논쟁

- 15 Bigamy of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse필리포스 1세 비가미, 헤세의 랜드그레이브

- 16 Antisemitism반유대주의

- 17 Final years, illness and death말년, 병과 죽음

- 18 Legacy and commemoration유산 및 기념

- 19 Luther and the swan루터와 백조

- 20 Works and editions작업 및 에디션

- 21 See also참고 항목

- 22 References참조

- 23 Sources원천

- 24 Further reading추가 읽기

- 25 External links외부 링크

Early life초년기

Birth and education출생과 교육

Portraits of Hans and Margarethe Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 15271527년 루카스 크리아흐 장로가 그린 한스와 마르가레 루터의 초상화

Former monks' dormitory, St Augustine's Monastery, Erfurt에르푸르트 성 아우구스티누스 수도원 옛 수도사 기숙사

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther)[12] and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on 10 November 1483 in Eisleben, County of Mansfeld in the Holy Roman Empire.마틴 루터는 1483년 11월 10일 신성로마제국 맨스펠드 카운티 아이슬레벤에서 한스 루더(또는 루더, 후기 루터)[12]와 그의 아내 마르가레테(네 린데만) 사이에서 태어났다. Luther was baptized the next morning on the feast day of St. 루터는 다음 날 아침 성탄절에 세례를 받았다. Martin of Tours. 투어의 마틴. His family moved to Mansfeld in 1484, where his father was a leaseholder of copper mines and smelters[13] and served as one of four citizen representatives on the local council; in 1492 he was elected as a town councilor.[14][12] 그의 가족은 1484년 만스펠트로 이주하여 아버지가 구리광산과 제련소의[13] 임대주자로 지방의회의 4명의 시민대표 중 한 명으로 활동했고, 1492년 그는 시의원으로 선출되었다.[14][12] The religious scholar Martin Marty describes Luther's mother as a hard-working woman of "trading-class stock and middling means" and notes that Luther's enemies later wrongly described her as a whore and bath attendant.[12] 종교학자 마르틴 마티는 루터의 어머니를 '트레이딩 계급의 주식과 중간계급 수단'의 근면한 여성으로 묘사하고 있으며, 루터의 적들이 나중에 루터의 어머니를 창녀와 목욕탕 수행원으로 잘못 묘사했다는 점에 주목한다.[12]

He had several brothers and sisters and is known to have been close to one of them, Jacob.[15]그에게는 형제자매가 여러 명 있었는데 그 중 한 명인 야곱과 친분이 있었던 것으로 알려져 있다.[15] Hans Luther was ambitious for himself and his family, and he was determined to see Martin, his eldest son, become a lawyer. 한스 루터는 자신과 가족을 위해 야심을 품었고, 장남인 마틴이 변호사가 되는 것을 보고 결심이 섰다. He sent Martin to Latin schools in Mansfeld, then Magdeburg in 1497, where he attended a school operated by a lay group called the Brethren of the Common Life, and Eisenach in 1498.[16] 그는 마틴을 맨스펠트의 라틴어 학교에 보낸 다음 1497년 마그데부르크에 보냈고, 그곳에서 그는 평민의 브레트렌이라는 평신도 그룹이 운영하는 학교에 다녔고, 1498년에는 아이제나흐를 다녔다.[16] The three schools focused on the so-called "trivium": grammar, rhetoric, and logic. 세 학교는 문법, 수사학, 논리학 등 이른바 '트리비움'에 초점을 맞췄다. Luther later compared his education there to purgatory and hell.[17] 루터는 나중에 그곳의 교육을 연옥과 지옥에 비유했다.[17]

In 1501, at age 17, he entered the University of Erfurt, which he later described as a beerhouse and whorehouse.[18]1501년, 17세에 에르푸르트 대학에 입학했는데, 후에 그는 이것을 맥주집과 창녀집이라고 표현했다.[18] He was made to wake at four every morning for what has been described as "a day of rote learning and often wearying spiritual exercises."[18] 그는 매일 아침 4시에 일어나도록 만들어졌는데, 그것은 "로테 학습과 종종 지치는 정신적 운동의 날"[18]로 묘사되어 왔다. He received his master's degree in 1505.[19] 그는 1505년에 석사 학위를 받았다.[19]

Luther as a friar, with tonsure수도사로서의 루터, 편도선이 있는

Luther's accommodation in Wittenberg비텐베르크에 있는 루터의 숙소

In accordance with his father's wishes, he enrolled in law but dropped out almost immediately, believing that law represented uncertainty.[19]아버지의 뜻에 따라 그는 법률에 등록했지만 법이 불확실성을 나타낸다고 믿고 거의 즉시 중퇴했다.[19] Luther sought assurances about life and was drawn to theology and philosophy, expressing particular interest in Aristotle, William of Ockham, and Gabriel Biel.[19] 루터는 삶에 대한 확신을 추구했고 신학과 철학에 이끌려 아리스토텔레스, 오캄의 윌리엄, 가브리엘에 대한 특별한 관심을 표현했다.[19] He was deeply influenced by two tutors, Bartholomaeus Arnoldi von Usingen and Jodocus Trutfetter, who taught him to be suspicious of even the greatest thinkers[19] and to test everything himself by experience.[20] 그는 바르톨로마이오스 아놀드니 폰 위센과 조도쿠스 트루트페테르라는 두 명의 튜터에게 깊은 영향을 받았으며, 그는 그에게 위대한[19] 사상가라도 의심하고 경험으로 모든 것을 시험하도록 가르쳤다.[20]

Philosophy proved to be unsatisfying, offering assurance about the use of reason but none about loving God, which to Luther was more important.철학은 이성의 사용에 대해 확신을 주지만 루터에게는 이보다 더 중요한 신을 사랑하는 것에 대해서는 아무 것도 제공하지 않는 것으로 만족하지 않는 것으로 증명되었다. Reason could not lead men to God, he felt, and he thereafter developed a love-hate relationship with Aristotle over the latter's emphasis on reason.[20] 그는 이성이 인간을 신에게 인도할 수 없다고 느꼈고, 이후 이성에 대한 후자의 강조보다 아리스토텔레스와 사랑의 혐오 관계를 발전시켰다.[20] For Luther, reason could be used to question men and institutions, but not God. 루터에게 이성은 인간과 제도에 의문을 제기하는 데 사용될 수 있지만 신은 그렇지 않다. Human beings could learn about God only through divine revelation, he believed, and Scripture therefore became increasingly important to him.[20] 인간은 신의 계시를 통해서만 신에 대해 배울 수 있었고, 따라서 성경은 그에게 점점 더 중요해졌다.[20]

On 2 July 1505, while returning to university on horseback after a trip home, a lightning bolt struck near Luther during a thunderstorm.1505년 7월 2일 귀국 후 말을 타고 대학으로 돌아가던 중 뇌우가 몰아치는 동안 루터 근방에 번개가 쳤다. Later telling his father he was terrified of death and divine judgment, he cried out, "Help! 나중에 아버지에게 죽음과 신성한 판단을 두려워한다고 말하고는 외쳤다. "도와줘! Saint Anna, I will become a monk!"[21][22] 성 안나, 나는 스님이 될 거야!"[21][22] He came to view his cry for help as a vow he could never break. 그는 도움을 청하는 자신의 외침을 결코 꺾을 수 없는 서약으로 여기게 되었다. He left university, sold his books, and entered St. 그는 대학을 나와 책을 팔고 성으로 들어갔다. Augustine's Monastery in Erfurt on 17 July 1505.[23] 1505년 7월 17일 에르푸르트 아우구스티누스 수도원.[23] One friend blamed the decision on Luther's sadness over the deaths of two friends. 한 친구는 두 친구의 죽음에 대한 루터의 슬픔 때문에 이 결정을 비난했다. Luther himself seemed saddened by the move. 루터 자신도 그 움직임에 슬퍼하는 것 같았다. Those who attended a farewell supper walked him to the door of the Black Cloister. 송별 만찬에 참석한 사람들은 그를 블랙 클로이스터 문까지 바래다 주었다. "This day you see me, and then, not ever again," he said.[20] 그는 "오늘은 나를 보고 다시는 보지 않는다"고 말했다.[20] His father was furious over what he saw as a waste of Luther's education.[24] 그의 아버지는 그가 루터의 교육의 낭비라고 본 것에 대해 격노했다.[24]

Monastic life수도원 생활

A posthumous portrait of Luther as an Augustinian friar루터를 아우구스티누스 주교로 추증한 사후 초상화

Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to fasting, long hours in prayer, pilgrimage, and frequent confession.[25]루터는 금식, 기도의 긴 시간, 순례, 잦은 고해성사에 전념하며 아우구스티누스 질서에 몸을 바쳤다.[25] Luther described this period of his life as one of deep spiritual despair. 루터는 그의 삶의 이 시기를 깊은 정신적 절망의 시기라고 묘사했다. He said, "I lost touch with Christ the Savior and Comforter, and made of him the jailer and hangman of my poor soul."[26] Johann von Staupitz, his superior, pointed Luther's mind away from continual reflection upon his sins toward the merits of Christ. 그는 "구세주와 콤포터 그리스도와 연락이 끊겨 그를 불쌍한 내 영혼의 간수와 교수형자로 만들었다"[26]고 말했다.그의 상관인 요한 폰 슈타우피츠는 루터의 마음을 그리스도의 장점을 향한 그의 죄에 대한 끊임없는 성찰에서 멀어지게 했다. He taught that true repentance does not involve self-inflicted penances and punishments but rather a change of heart.[27] 그는 참된 회개는 자해와 처벌이 아니라 오히려 마음의 변화를 수반한다고 가르쳤다.[27]

On 3 April 1507, Jerome Schultz (lat.1507년 4월 3일, 제롬 슐츠(lat. Hieronymus Scultetus), the Bishop of Brandenburg, ordained Luther in Erfurt Cathedral. 브란덴부르크의 주교인 히에로니무스 스컬테투스는 에르푸르트 대성당에서 루터를 서품했다. In 1508, von Staupitz, first dean of the newly founded University of Wittenberg, sent for Luther to teach theology.[27][28] 1508년, 새로 설립된 비텐베르크 대학의 초대 학장인 폰 슈타우피츠는 루터에게 신학을 가르칠 것을 요청했다.[27][28] He received a bachelor's degree in Biblical studies on 9 March 1508 and another bachelor's degree in the Sentences by Peter Lombard in 1509.[29] 1508년 3월 9일 성서학 학사학위를 받았고 1509년 피터 롬버드의 문장학 학사학위를 받았다.[29] On 19 October 1512, he was awarded his Doctor of Theology and, on 21 October 1512, was received into the senate of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg,[30] having succeeded von Staupitz as chair of theology.[31] 1512년 10월 19일 신학 박사상을 받았고, 1512년 10월 21일 비텐베르크 대학의 신학 교수진 원로원에 입성하여 [30]폰 슈타우피츠를 신학 석좌로 승계하였다.[31] He spent the rest of his career in this position at the University of Wittenberg. 그는 비텐베르크 대학에서 이 직책에 남은 경력을 보냈다.

He was made provincial vicar of Saxony and Thuringia by his religious order in 1515.그는 1515년 그의 종교 질서에 의해 작센과 튜링야의 지방 대리인이 되었다. This meant he was to visit and oversee each of eleven monasteries in his province.[32] 이것은 그가 그의 지방에 있는 11개의 수도원을 각각 방문하여 감독하는 것을 의미했다.[32]

Start of the Reformation개혁의 시작

Further information:추가 정보: History of Protestantism and History of Lutheranism 개신교의 역사와 루터교의 역사

Luther's theses are engraved into the door of All Saints' Church, Wittenberg.루터의 논문들이 비텐베르크 올세인트 교회의 문에 새겨져 있다. The Latin inscription above informs the reader that the original door was destroyed by a fire, and that in 1857, King Frederick William IV of Prussia ordered a replacement be made. 위의 라틴어 비문은 독자에게 원래의 문이 화재로 소실되었음을 알려주고, 1857년 프로이센의 프레데릭 윌리엄 4세가 교체를 명령했다는 것을 알려준다.

In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money in order to rebuild St.1516년, 도미니카 출신의 요한 테첼은 로마 가톨릭 교회에서 독일로 보내져 성 재건을 위해 돈을 모으기 위한 면죄부를 팔게 되었다. Peter's Basilica in Rome.[33] 로마의 베드로 대성당.[33] Tetzel's experiences as a preacher of indulgences, especially between 1503 and 1510, led to his appointment as general commissioner by Albrecht von Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, who, deeply in debt to pay for a large accumulation of benefices, had to contribute a considerable sum toward the rebuilding of St. 테첼의 면죄부 전도사로서의 경험, 특히 1503년에서 1510년 사이는 마인츠의 대주교 알브레히트 폰 브란덴부르크에 의해 총위원으로 임명되게 되었는데, 그는 거액의 은인 축적을 위해 빚더미에 올라앉은 것은 성 재건에 상당한 금액을 기부해야 했다. Peter's Basilica in Rome. 로마의 베드로 대성당. Albrecht obtained permission from Pope Leo X to conduct the sale of a special plenary indulgence (i.e., remission of the temporal punishment of sin), half of the proceeds of which Albrecht was to claim to pay the fees of his benefices. 알브레히트는 교황 레오 10세로부터 특별 전관 면죄부(즉, 죄의 일시적 처벌의 해제)의 판매 허가를 받았는데, 이 수익금의 절반은 알브레히트가 자신의 은인들의 수수료를 지불하라고 주장하는 것이었다.

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, protesting against the sale of indulgences.1517년 10월 31일 루터는 주교 알브레히트 폰 브란덴부르크에게 면죄부 판매에 항의하는 편지를 보냈다. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his "Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences", which came to be known as the Ninety-five Theses. 그는 편지에 '구백오십일장'으로 알려지게 된 자신의 '마틴 루터의 권력과 효능에 관한 폭로' 한 권을 동봉했다. Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly "searching, rather than doctrinaire."[34] 한스 힐러브란드는 루터가 교회와 맞설 생각은 없었지만 그의 분열을 교회 관행에 대한 학자적 거부로 보았고, 따라서 글의 어조는 "교조적이라기보다는 탐구적"이라고 쓰고 있다.[34] Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks: "Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. 힐러브란드는 특히 논문 86에서 "왜 오늘날 가장 부유한 크라수스의 재산보다 더 큰 교황이 성 성당 성당을 짓느냐"고 묻는 논문에는 도전이라는 저류가 있다고 쓰고 있다. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?"[34] 자기 돈보다는 가난한 신자들의 돈으로 베드로?"[34]

The Catholic sale of indulgences shown in A Question to a Mintmaker, woodcut by Jörg Breu the Elder of Augsburg, ca. 1530아우크스부르크의 장로 요르그 브뢰가 목판화한 민트 제조자에게의 질문에서 나타난 가톨릭의 면죄부 판매. ca. 1530

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory (also attested as 'into heaven') springs."[35]루터는 "커피 속의 동전이 울리자마자 연옥에서 나온 영혼이 샘솟는다"는 테첼의 말에 반대했다.[35] He insisted that, since forgiveness was God's alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. 그는 용서가 하나님만이 허락하는 것이기 때문에, 면죄부가 구매자들을 모든 처벌로부터 면제해 주고 구원을 허락했다고 주장하는 사람들은 잘못된 것이라고 주장했다. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances. 그는 기독교인들은 그러한 거짓된 확약을 이유로 그리스도를 따르는 데 게으름을 피워서는 안 된다고 말했다.

According to one account, Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the door of All Saints' Church in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517.한 가지 설명에 따르면, 루터는 1517년 10월 31일 비텐베르크에 있는 모든 성도의 문에 그의 95년 세제를 못박았다. Scholars Walter Krämer, Götz Trenkler, Gerhard Ritter, and Gerhard Prause contend that the story of the posting on the door, even though it has settled as one of the pillars of history, has little foundation in truth.[36][37][38][39] 학자인 월터 크레이머, 괴츠 트렌클러, 게르하르트 리터, 게르하르트 프라우스 등은 문 위에 올린 글이 역사의 한 축으로 자리 잡았음에도 불구하고 사실상의 근거가 거의 없다고 주장한다.[36][37][38][39] The story is based on comments made by Luther's collaborator Philip Melanchthon, though it is thought that he was not in Wittenberg at the time.[40] 당시 비텐베르크에 없었던 것으로 생각되지만 루터의 협력자 필립 멜랑크톤이 한 발언을 바탕으로 한 이야기다.[40]

The Latin Theses were printed in several locations in Germany in 1517.라틴어 Theses는 1517년 독일의 여러 지역에서 인쇄되었다. In January 1518 friends of Luther translated the Ninety-five Theses from Latin into German.[41] 1518년 1월 루터의 친구들은 라틴어에서 독일어로 구십오 세제를 번역했다.[41] Within two weeks, copies of the theses had spread throughout Germany. 2주 안에 그 논문들의 복사본이 독일 전역에 퍼졌다. Luther's writings circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519. 루터의 글은 널리 퍼져서 1519년 프랑스, 영국, 이탈리아에 이르렀다. Students thronged to Wittenberg to hear Luther speak. 학생들이 루터의 연설을 듣기 위해 비텐베르크로 몰려들었다. He published a short commentary on Galatians and his Work on the Psalms. 그는 갈라디아인들과 시편들에 대한 그의 작품에 대한 짧은 논평을 발표했다. This early part of Luther's career was one of his most creative and productive.[42] 루터 경력의 이 초기 부분은 그의 가장 창의적이고 생산적인 부분 중 하나였다.[42] Three of his best-known works were published in 1520: 그의 가장 유명한 세 작품은 1520년에 출판되었다. To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian. 독일 국가의 기독교 귀족, 교회의 바빌로니아 포로, 그리고 기독교인의 자유에 대하여.

Justification by faith alone믿음만으로 정당화

Main article:주요 기사: Sola fide 솔라피드

"Luther at Erfurt", which depicts Martin Luther discovering the doctrine of sola fide (by faith alone).마틴 루터가 (믿음만으로) 솔라피드의 교리를 발견하는 모습을 그린 '에르푸르트에서의 루터'이다. Painting by Joseph Noel Paton, 1861. 1861년 조셉 노엘 패튼의 그림.

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians.1510년부터 1520년까지 루터는 시편과 히브리인, 로마인, 갈라트인 등의 책을 강의하였다. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as penance and righteousness by the Catholic Church in new ways. 그는 성경의 이러한 부분을 연구하면서 가톨릭 교회의 참회, 의와 같은 용어의 사용을 새로운 시각으로 보게 되었다. He became convinced that the church was corrupt in its ways and had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity. 그는 교회가 부패했다고 확신하게 되었고 기독교의 몇 가지 중심적 진리로 보는 것을 보지 못하게 되었다. The most important for Luther was the doctrine of justification—God's act of declaring a sinner righteous—by faith alone through God's grace. 루터에게 가장 중요한 것은 하나님의 은총을 통해 오직 믿음만으로 죄인을 의롭게 선포하는 하나님의 행위인 정당성 교리였다. He began to teach that salvation or redemption is a gift of God's grace, attainable only through faith in Jesus as the Messiah.[43] 구원과 구원은 하나님의 은총의 선물이며, 오직 메시아로서 예수를 믿는 믿음을 통해서만 얻을 수 있다는 것을 가르치기 시작했다.[43] "This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification", he writes, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness."[44] 그는 "우리가 명분주의 교리라고 부르는 이 하나뿐인 확고한 바위"라고 쓰고 있는데, "모든 경건함에 대한 이해를 이해하는 전체 기독교 교리의 주요 조항"이라고 한다.[44]

Luther came to understand justification as entirely the work of God.루터는 정당성을 전적으로 하나님의 일로 이해하게 되었다. This teaching by Luther was clearly expressed in his 1525 publication On the Bondage of the Will, which was written in response to On Free Will by Desiderius Erasmus (1524). 루터의 이러한 가르침은 데시데리우스 에라스무스의 '자유 의지에 대하여'(1524년)에 대한 응답으로 쓰여진 1525년 간행물 '의지의 속박에 대하여'에 분명히 나타나 있다. Luther based his position on predestination on St. Paul's epistle to the Ephesians 2:8–10. Against the teaching of his day that the righteous acts of believers are performed in cooperation with God, Luther wrote that Christians receive such righteousness entirely from outside themselves; that righteousness not only comes from Christ but actually i 루터는 에베소서 성 바울이 에베소서 2장 8~10절을 기점으로 자신의 입장을 밝혔다.신자들의 의로운 행위는 하나님과 협력하여 행해진다는 당시의 가르침에 반해 루터는 기독교인들은 전적으로 외부로부터 그러한 의를 받는다고 썼다.그 의로운 것은 그리스도뿐만 아니라 실제로 나로부터도 온다고 썼다.s the righteousness of Christ, imputed to Christians (rather than infused into them) through faith.[45]믿음을 통해 기독교인들에게 귀속된 그리스도의 의로움.[45]

"That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law," he writes.그는 "그래서 믿음만이 누군가를 정의롭게 만들고 법을 이행하는 것"이라고 썼다. "Faith is that which brings the Holy Spirit through the merits of Christ."[46] "신앙은 그리스도의 장점을 통해 성령을 인도하는 것이다."[46] Faith, for Luther, was a gift from God; the experience of being justified by faith was "as though I had been born again." 루터에게 믿음은 신이 내린 선물이었다. 믿음으로 정당화된 경험은 "내가 다시 태어난 것처럼"이었다. His entry into Paradise, no less, was a discovery about "the righteousness of God"—a discovery that "the just person" of whom the Bible speaks (as in Romans 1:17) lives by faith.[47] 그가 파라다이스에 들어간 것도 마찬가지로 '신의 의'에 대한 발견이었다. 즉 성경이 말하는 (로마 1:17처럼) '정당한 사람'이 믿음으로 살아간다는 발견이었다.[47] He explains his concept of "justification" in the Smalcald Articles: 그는 스말칼드 조항에서 "정당한 것"에 대한 자신의 개념을 설명한다.

The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24–25).첫 번째와 주요 기사는 다음과 같다: 우리의 하나님과 주 예수 그리스도는 우리의 죄를 위해 죽으시고 우리의 정당성을 위해 다시 양육되었다(롬 3:24–25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah 53:6). 그 혼자만이 세상의 죄(요 1:29)를 앗아가는 하나님의 어린양이고, 하나님은 우리 모두의 죄(이사야 53:6)를 그에게 내려 주셨다. All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23–25). 모든 사람은 자신의 업적과 공적이 없이 그리스도의 은혜로 말미암아 그리스도의 피 속에 있는 구원을 통하여(로맨 3:23–25) 죄를 지었고 자유롭게 정당화되었다. This is necessary to believe. 이것은 믿을 필요가 있다. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law or merit. 이것은 다른 방법으로는 어떤 일, 법률 또는 공적에 의해서도 획득되거나 파악될 수 없다. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us ... 그러므로, 이 믿음만이 우리를 정당화한다는 것은 분명하고 확실하다... Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).[48] 하늘과 땅과 그 밖의 모든 것이 무너지더라도 이 글의 어떤 것도 양보하거나 항복할 수 없다(마크 13:31).[48]

Luther's rediscovery of "Christ and His salvation" was the first of two points that became the foundation for the Reformation.루터가 '기독교와 그의 구원'을 재발견한 것은 종교개혁의 토대가 된 두 점 중 첫 번째였다. His railing against the sale of indulgences was based on it.[49] 면죄부 판매에 반대하는 그의 난간은 그것에 근거를 두고 있었다.[49]

Breach with the papacy교황직 위반

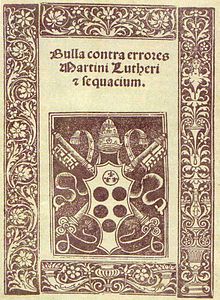

Pope Leo X's Bull against the errors of Martin Luther, 1521, commonly known as Exsurge Domine흔히 엑서지 도미네로 알려진 1521년 마르틴 루터의 실수에 반대하는 교황 레오 14세의 불

Archbishop Albrecht did not reply to Luther's letter containing the Ninety-five Theses.알브레히트 대주교는 95세제가 담긴 루터의 편지에 답하지 않았다. He had the theses checked for heresy and in December 1517 forwarded them to Rome.[50] 그는 논문에서 이단 여부를 확인하게 하고 1517년 12월에 로마로 보냈다.[50] He needed the revenue from the indulgences to pay off a papal dispensation for his tenure of more than one bishopric. 그는 한 명 이상의 주교직에 대한 교황의 허가를 얻기 위해 면죄부로부터의 수입이 필요했다. As Luther later notes, "the pope had a finger in the pie as well, because one half was to go to the building of St Peter's Church in Rome".[51] 루터가 나중에 언급했듯이, "로마의 성 베드로 교회 건물로 가는 것이 절반이었기 때문에 교황도 파이에 손가락이 있었다."[51]

Pope Leo X was used to reformers and heretics,[52] and he responded slowly, "with great care as is proper."[53]교황 레오 10세는 개혁자와 이단자에 익숙했고,[52] 그는 "적절한 만큼 세심하게" 느리게 반응했다.[53] Over the next three years he deployed a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther, which served only to harden the reformer's anti-papal theology. 이후 3년 동안 그는 루터를 상대로 교황 신학자와 사신을 잇달아 배치했는데, 이는 개혁자의 반파벌 신학을 굳히는 데만 기여했다. First, the Dominican theologian Sylvester Mazzolini drafted a heresy case against Luther, whom Leo then summoned to Rome. 먼저 도미니카 신학자 실베스터 마졸리니는 루터를 상대로 이단 사건을 초안했고, 리오는 로마로 소환했다. The Elector Frederick persuaded the pope to have Luther examined at Augsburg, where the Imperial Diet was held.[54] 프레드릭 일렉트릭 당선자는 교황에게 제국주의 의회가 열린 아우크스부르크에서 루터를 검진하라고 설득했다.[54] Over a three-day period in October 1518, Luther defended himself under questioning by papal legate Cardinal Cajetan. 1518년 10월 3일 동안 루터는 교황 공관인 카제탄 추기경의 심문을 받으며 자신을 변호했다. The pope's right to issue indulgences was at the centre of the dispute between the two men.[55][56] 교황의 면죄부 발급권은 두 사람 사이의 논쟁의 중심에 있었다.[55][56] The hearings degenerated into a shouting match. 청문회는 고함지기로 전락했다 More than writing his theses, Luther's confrontation with the church cast him as an enemy of the pope.[57] 논문을 쓰는 것 이상으로 루터가 교회와 대립하면서 그는 교황의 적으로 간주되었다.[57] Cajetan's original instructions had been to arrest Luther if he failed to recant, but the legate desisted from doing so.[58] 카제탄의 원래 지시는 루터가 물러나지 않을 경우 체포하라는 것이었으나, 입법부는 이를 거부했다.[58] With help from the Carmelite monk Christoph Langenmantel, Luther slipped out of the city at night, unbeknownst to Cajetan.[59] 카멜라이트 수도사 크리스토프 랑겐만텔의 도움으로 루터는 밤중에 카제탄에게 들키지 않고 그 도시를 빠져나갔다.[59]

The meeting of Martin Luther (right) and Cardinal Cajetan (left, holding the book)마틴 루터(오른쪽)와 카제탄 추기경(왼쪽, 책을 들고 있음)의 만남.

In January 1519, at Altenburg in Saxony, the papal nuncio Karl von Miltitz adopted a more conciliatory approach.1519년 1월 작센의 알텐부르크에서 교황 수녀 카를 폰 밀티츠가 보다 유화적인 접근법을 채택했다. Luther made certain concessions to the Saxon, who was a relative of the Elector, and promised to remain silent if his opponents did.[60] 루터는 일렉트로르의 친척이었던 색슨족에게 일정한 양보를 했고, 상대가 그렇게 한다면 침묵을 지키겠다고 약속했다.[60] The theologian Johann Eck, however, was determined to expose Luther's doctrine in a public forum. 그러나 신학자 요한 에크는 공개 토론회에서 루터의 교리를 폭로할 작정이었다. In June and July 1519, he staged a disputation with Luther's colleague Andreas Karlstadt at Leipzig and invited Luther to speak.[61] 1519년 6월과 7월에는 라이프치히에서 루터의 동료 안드레아스 칼슈타트와 분열을 일으켜 루터를 초청하여 연설을 하였다.[61] Luther's boldest assertion in the debate was that Matthew 16:18 does not confer on popes the exclusive right to interpret scripture, and that therefore neither popes nor church councils were infallible.[62] 루터의 가장 대담한 주장은 마태복음 16장 18절은 교황에게 경전 해석 독점권을 부여하지 않으며, 따라서 교황이나 교회의회도 절대적으로 부정할 수 없다는 것이었다.[62] For this, Eck branded Luther a new Jan Hus, referring to the Czech reformer and heretic burned at the stake in 1415. 이를 위해 Eck는 1415년 체코 개혁가와 이단자를 언급하며 루터를 새로운 얀 허스로 낙인찍었다. From that moment, he devoted himself to Luther's defeat.[63] 그 순간부터 그는 루터의 패배를 위해 헌신했다.[63]

Excommunication통신 해제

On 15 June 1520, the pope warned Luther with the papal bull (edict) Exsurge Domine that he risked excommunication unless he recanted 41 sentences drawn from his writings, including the Ninety-five Theses, within 60 days.1520년 6월 15일 교황은 교황 황소(독재) 엑수르지 도미네와 함께 루터에게 "구십오 세제를 포함한 자신의 저술에서 뽑은 41개의 문장을 60일 이내에 철회하지 않으면 파문을 감수할 위험이 있다"고 경고했다. That autumn, Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. 그해 가을, 에크는 메이센과 다른 마을에 황소를 선포했다. Von Miltitz attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the pope a copy of On the Freedom of a Christian in October, publicly set fire to the bull and decretals at Wittenberg on 10 December 1520,[64] an act he defended in Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned and Assertions Concerning All Articles. 폰 밀티츠는 해결책을 중개하려 했으나, 지난 10월 교황에게 '기독교인의 자유에 관한' 사본을 보냈던 루터가 1520년 12월 10일 비텐베르크에서 공개적으로 소와 소에게 불을 질렀는데,[64] 이는 교황과 그의 최근 책이 왜 불태워졌는지와 모든 조항에 관한 주장에서 옹호한 행동이다. As a consequence, Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X on 3 January 1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem.[65] 그 결과 루터는 1521년 1월 3일 교황 레오 10세에 의해 황소 데케 로마눔 폰티페렘에서 파문되었다.[65] And although the Lutheran World Federation, Methodists and the Catholic Church's Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity agreed (in 1999 and 2006, respectively) on a "common understanding of justification by God's grace through faith in Christ," the Catholic Church has never lifted the 1520 excommunication.[66][67][68] 그리고 루터교 세계연맹, 감리교도와 가톨릭교회의 기독교통합촉진을 위한 교황협의회가 각각 1999년과 2006년 '예수에 대한 신앙을 통한 하나님의 은혜에 의한 정당화에 대한 공동의 이해'에 합의했지만, 가톨릭교회는 1520년 파문을 푼 적이 없다.[66][67][68]

Diet of Worms벌레의 식단

Main article:주요 기사: Diet of Worms 벌레의 식단

Luther Before the Diet of Worms by Anton von Werner (1843–1915)안톤 폰 베르너 (1843–1915)에 의한 벌레의 식전 루터

The enforcement of the ban on the Ninety-five Theses fell to the secular authorities.구십오 세파에 대한 금지의 집행은 세속 당국에 떨어졌다. On 18 April 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the Diet of Worms. 1521년 4월 18일 루터는 벌레의 식전에 명령한 대로 나타났다. This was a general assembly of the estates of the Holy Roman Empire that took place in Worms, a town on the Rhine. 이것은 라인 강에 있는 마을인 웜스에서 일어난 신성로마제국 영지의 총회였다. It was conducted from 28 January to 25 May 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding. 1521년 1월 28일부터 5월 25일까지 황제 찰스 5세가 주재한 가운데 실시되었다. Prince Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, obtained a safe conduct for Luther to and from the meeting. 작센의 선출자인 프레데릭 3세 왕자는 루터를 위해 회의를 오가며 안전한 행동을 얻었다.

Johann Eck, speaking on behalf of the empire as assistant of the Archbishop of Trier, presented Luther with copies of his writings laid out on a table and asked him if the books were his and whether he stood by their contents.요한 에크는 트리에르 대주교의 조수로 제국을 대신하여 말하면서 루터에게 그의 저술 사본을 탁자 위에 펼쳐 놓고, 그 책들이 그의 것이었는지, 그리고 그가 그 책들의 내용을 지키고 서 있는지 물었다. Luther confirmed he was their author but requested time to think about the answer to the second question. 루터는 자신이 그들의 작가임을 확인했지만 두 번째 질문에 대한 답을 생각해 볼 시간을 요구했다. He prayed, consulted friends, and gave his response the next day: 그는 기도하고, 친구들과 상의하고, 다음날 이렇게 대답하였다.

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God.내가 성경의 증언이나 분명한 이성에 의해 납득되지 않는 한(나는 교황이나 의회만을 신뢰하지 않기 때문에, 그들이 자주 잘못을 저지르고 모순된 것으로 잘 알려져 있기 때문에), 나는 내가 인용한 성경에 얽매여 있고 나의 양심은 하나님의 말씀에 사로잡혀 있다. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. 양심에 역행하는 것은 안전하지도 않고 권리도 없기 때문에 나는 어떤 것도 철회할 수 없고 또 철회하지 않을 것이다. May God help me. 신이 나를 도와주기를. Amen.[69] 아멘[69]

At the end of this speech, Luther raised his arm "in the traditional salute of a knight winning a bout."이 연설이 끝나자 루터는 "한 판에 이긴 기사의 전통적인 경례에서" 팔을 들었다. Michael Mullett considers this speech as a "world classic of epoch-making oratory."[70] 마이클 멀렛은 이 연설을 "시대적인 웅변술의 세계 고전"[70]으로 여긴다.

Luther Monument in Worms.웜스의 루터 기념비 His statue is surrounded by the figures of his lay protectors and earlier Church reformers including John Wycliffe, Jan Hus and Girolamo Savonarola. 그의 동상은 존 와이클리프, 얀 후스, 지롤라모 사보나롤라 등 그의 평신도들과 초기 교회 개혁가들의 모습으로 둘러싸여 있다.

Eck informed Luther that he was acting like a heretic, saying, 에크는 루터에게 자신이 이단자처럼 행동하고 있다는 것을 알리며 이렇게 말했다.

Martin, there is no one of the heresies which have torn the bosom of the church, which has not derived its origin from the various interpretation of the Scripture.마틴, 교회의 가슴을 찢어놓은 이단 중에 성경의 다양한 해석에서 유래하지 못한 것은 하나도 없다. The Bible itself is the arsenal whence each innovator has drawn his deceptive arguments. 성서 그 자체는 각 혁신자들이 그의 기만적인 주장을 이끌어낸 무기고의 시기다. It was with Biblical texts that Pelagius and Arius maintained their doctrines. 펠라기우스와 아리우스가 교리를 견지한 것은 성경의 문헌과 함께였다. Arius, for instance, found the negation of the eternity of the Word—an eternity which you admit, in this verse of the New Testament—Joseph knew not his wife till she had brought forth her first-born son; and he said, in the same way that you say, that this passage enchained him. 예를 들어, 아리우스는 신약성서의 이 구절에서 당신이 인정하는 영원성인 말씀의 영원성을 부정하는 것을 발견하였다. 요셉은 첫아들을 데리고 나올 때까지 아내를 알지 못했다. 요셉은 당신이 말하는 것과 마찬가지로 이 구절이 그를 매혹시켰다고 말했다. When the fathers of the Council of Constance condemned this proposition of Jan Hus— 콘스탄스 평의회의 아버지들이 얀 후스의 이 제안을 비난했을 때,The church of Jesus Christ is only the community of the elect, they condemned an error; for the church, like a good mother, embraces within her arms all who bear the name of Christian, all who are called to enjoy the celestial beatitude.[71]예수 그리스도의 교회는 오직 선택받은 자들의 공동체일 뿐이다. 그들은 잘못을 규탄했다. 교회는 선한 어머니처럼 기독교인의 이름을 가진 모든 사람을 그녀의 품 안에 끌어안고, 천상의 구애를 즐기라고 불려지는 모든 사람들을 포용하기 때문이다.[71]

Luther refused to recant his writings.루터는 그의 글을 철회하기를 거부했다. He is sometimes also quoted as saying: "Here I stand. 그는 또한 때때로 이렇게 말한 것으로 인용된다: "여기 내가 서 있다. I can do no other". 다른 건 할 수 없다"고 말했다. Recent scholars consider the evidence for these words to be unreliable, since they were inserted before "May God help me" only in later versions of the speech and not recorded in witness accounts of the proceedings.[72] 최근의 학자들은 이 단어들이 "하느님이 나를 도와주소서" 앞에 삽입되었고, 의사진행의 목격자 진술에는 기록되지 않았기 때문에 이 단어들에 대한 증거를 신뢰할 수 없다고 생각한다.[72] However, Mullett suggests that given his nature, "we are free to believe that Luther would tend to select the more dramatic form of words."[70] 그러나 뮬렛은 "루터가 더 극적인 형태의 단어를 선택하는 경향이 있을 것이라고 믿는 것은 자유롭다"고 그의 성격에 비추어 볼 때 제안한다.[70]

Over the next five days, private conferences were held to determine Luther's fate.이후 5일 동안 루터의 운명을 결정하는 비공개 회의가 열렸다. The emperor presented the final draft of the Edict of Worms on 25 May 1521, declaring Luther an outlaw, banning his literature, and requiring his arrest: "We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic."[73] 황제는 1521년 5월 25일 벌레의 칙령 최종 초안을 제시하여 루터를 무법자로 선언하고 그의 문학을 금지하며 "우리는 그가 악명 높은 이단으로 체포되어 처벌받기를 원한다"고 체포를 요구했다.[73] It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter. 또한 루터에게 음식이나 은신처를 주는 것은 독일의 어느 누구라도 범죄로 만들었다. It permitted anyone to kill Luther without legal consequence. 그것은 누구든지 법적인 영향 없이 루터를 죽일 수 있도록 허락했다.

At Wartburg Castle바르트부르크 성에서

Wartburg Castle, Eisenach아이제나흐 주 바르트부르크 성

The Wartburg room where Luther translated the New Testament into German.루터가 신약성서를 독일어로 번역한 바르트부르크 방. An original first edition is kept in the case on the desk. 초판 원본은 책상 위의 케이스에 보관되어 있다.

Luther's disappearance during his return to Wittenberg was planned.루터가 비텐베르크로 돌아오는 동안 사라진 것은 계획적이었다. Frederick III had him intercepted on his way home in the forest near Wittenberg by masked horsemen impersonating highway robbers. 프레데릭 3세는 비텐베르크 근처의 숲에서 집으로 돌아오는 길에 고속도로 강도들을 사칭한 복면을 쓴 기병들에게 그를 가로챘다. They escorted Luther to the security of the Wartburg Castle at Eisenach.[74] 그들은 루터를 아이제나흐의 바르트부르크 성 보안으로 호송했다.[74] During his stay at Wartburg, which he referred to as "my Patmos",[75] Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German and poured out doctrinal and polemical writings. 루터는 '나의 패트모스'[75]라고 지칭한 바르트부르크에 머무는 동안 그리스어에서 독일어로 신약성서를 번역하고 교조적이고 장황한 글을 쏟아냈다. These included a renewed attack on Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, whom he shamed into halting the sale of indulgences in his episcopates,[76] and a "Refutation of the Argument of Latomus," in which he expounded the principle of justification to Jacobus Latomus, an orthodox theologian from Louvain.[77] 여기에는 자신이 주교에서 면죄부 판매를 중단하도록 부끄러운 마인츠 대주교 알브레히트에 대한 새로운 공격과 [76]루뱅 출신의 정통 신학자 야코부스 라토무스에게 명분론의 원리를 상세히 설명한 '라토무스 논쟁의 반박' 등이 포함됐다.[77] In this work, one of his most emphatic statements on faith, he argued that every good work designed to attract God's favor is a sin.[78] 신앙에 관한 그의 가장 강력한 진술 중 하나인 이 작품에서 그는 신의 환심을 사기 위해 고안된 모든 좋은 작품은 죄악이라고 주장했다.[78] All humans are sinners by nature, he explained, and God's grace (which cannot be earned) alone can make them just. 모든 인간은 천성적으로 죄인이며, (벌 수 없는) 하나님의 은혜만이 그들을 정당하게 만들 수 있다고 그는 설명했다. On 1 August 1521, Luther wrote to Melanchthon on the same theme: "Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. 1521년 8월 1일 루터는 멜랑숑에게 같은 주제로 편지를 썼다. "죄인이 되어라, 네 죄가 강해지되 그리스도에 대한 믿음이 강해지도록 하라. 그리고 죄와 죽음과 세상을 이기는 그리스도를 기뻐하라. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides."[79] 이 생명은 정의가 깃든 곳이 아니니 우리가 여기 있는 동안 죄를 짓겠다."[79]

In the summer of 1521, Luther widened his target from individual pieties like indulgences and pilgrimages to doctrines at the heart of Church practice.1521년 여름, 루터는 그의 목표를 면죄부나 순례와 같은 개별적인 피에티에서 교회 실천의 핵심에 있는 교리까지 넓혔다. In On the Abrogation of the Private Mass, he condemned as idolatry the idea that the mass is a sacrifice, asserting instead that it is a gift, to be received with thanksgiving by the whole congregation.[80] 그는 '사적 미사절단'에 대해 "미사절은 희생"이라고 우상숭배하며 대신 "선물"이라고 주장하면서 전체 신도들에게 감사와 함께 받아야 한다고 비난했다.[80] His essay On Confession, Whether the Pope has the Power to Require It rejected compulsory confession and encouraged private confession and absolution, since "every Christian is a confessor."[81] 그의 에세이 '고백에 관한 고백에 관한, 교황이 요구하는 힘이 있는가'는 "모든 기독교인은 고백자"라는 이유로 강제적인 고백을 거부하고 사적인 고백과 용서를 장려했다.[81] In November, Luther wrote The Judgement of Martin Luther on Monastic Vows. 11월에 루터는 <마틴 루터의 성서약>을 썼다. He assured monks and nuns that they could break their vows without sin, because vows were an illegitimate and vain attempt to win salvation.[82] 그는 승려와 수녀들에게 서약은 구원을 얻기 위한 사생적이고 허망한 시도였기 때문에 죄 없이 서약을 어길 수 있다고 확신시켰다.[82]

Luther disguised as "Junker Jörg", 1521루터는 1521년 "Junker Jörg"로 변장했다.

In 1521 Luther dealt largely with prophecy, in which he broadened the foundations of the Reformation, placing them on prophetic faith.1521년 루터는 주로 예언에 대해 다루었는데, 그 예언에서 그는 종교개혁의 기초를 넓혀서 예언 신앙에 두었다. His main interest was centered on the prophecy of the Little Horn in Daniel 8:9–12, 23–25. 그의 주된 관심사는 대니얼 8:9–12, 23–25의 리틀 혼의 예언에 집중되었다. The antichrist of 2 Thessalonians 2 was identified as the power of the Papacy. 2 테살로니아인 2세의 적그리스도는 교황의 권력으로 확인되었다. So too was the Little Horn of Daniel 7, coming up among the divisions of Rome, explicitly applied.[83] 로마의 사단들 사이에 올라오는 다니엘 7의 작은 뿔도 분명히 적용되었다.[83]

Luther made his pronouncements from Wartburg in the context of rapid developments at Wittenberg, of which he was kept fully informed.루터는 비텐베르크에서 급속한 발전을 이룬 맥락에서 바르트부르크로부터 그의 선언문을 발표했는데, 그 내용을 충분히 알고 있었다. Andreas Karlstadt, supported by the ex-Augustinian Gabriel Zwilling, embarked on a radical programme of reform there in June 1521, exceeding anything envisaged by Luther. 전 아우구스티니아인 가브리엘 즈윌링의 지지를 받은 안드레아스 칼슈타트는 1521년 6월 루터가 구상하는 어떤 것을 능가하는 급진적인 개혁 프로그램에 착수했다. The reforms provoked disturbances, including a revolt by the Augustinian friars against their prior, the smashing of statues and images in churches, and denunciations of the magistracy. 그 개혁은 이전부터의 아우구스티누스 수도회들의 반란을 일으켰고, 교회에서의 동상과 이미지의 파괴, 치안판사의 비난 등 소란을 일으켰다. After secretly visiting Wittenberg in early December 1521, Luther wrote A Sincere Admonition by Martin Luther to All Christians to Guard Against Insurrection and Rebellion.[84] 루터는 1521년 12월 초 비밀리에 비텐베르크를 방문한 후, 모든 기독교인들에게 '반란과 반란을 경계하기 위한 마틴 루터의 성실한 훈계'를 썼다.[84] Wittenberg became even more volatile after Christmas when a band of visionary zealots, the so-called Zwickau prophets, arrived, preaching revolutionary doctrines such as the equality of man,[clarification needed] adult baptism, and Christ's imminent return.[85] 비텐베르크는 크리스마스 이후 인간의 평등,[clarification needed] 성인 세례, 그리스도의 임박한 귀환과 같은 혁명적 교리를 설교하는 이른바 즈위카우 예언자 무리들이 도착하자 더욱 휘발성이 커졌다.[85] When the town council asked Luther to return, he decided it was his duty to act.[86] 마을 의회가 루터에게 돌아오라고 요구했을 때, 그는 행동하는 것이 그의 의무라고 결정했다.[86]

Return to Wittenberg and Peasants' War비텐베르크와 농민 전쟁으로 돌아가기

See also: Radical Reformation and German Peasants' War참고 항목: 급진적 개혁과 독일 농민 전쟁

Lutherhaus, Luther's residence in Wittenberg루터하우스, 비텐베르크에 있는 루터의 거주지

Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on 6 March 1522.루터는 1522년 3월 6일 비밀리에 비텐베르크로 돌아왔다. He wrote to the Elector: "During my absence, Satan has entered my sheepfold, and committed ravages which I cannot repair by writing, but only by my personal presence and living word."[87] 그는 엘렉터에게 다음과 같이 썼다. `내가 없는 동안에, 사탄은 나의 양피지에 들어가서, 내가 글로써 고칠 수 없는, 다만 나의 개인적인 존재와 살아 있는 말만으로 고칠 수 없는 파괴를 저질렀다.'[87] For eight days in Lent, beginning on Invocavit Sunday, 9 March, Luther preached eight sermons, which became known as the "Invocavit Sermons". 3월 9일 일요일 인보카빗을 시작으로 사순절 8일간 루터는 8개의 설교를 설교했는데, 이 설교는 "인보카빗 설교"로 알려지게 되었다. In these sermons, he hammered home the primacy of core Christian values such as love, patience, charity, and freedom, and reminded the citizens to trust God's word rather than violence to bring about necessary change.[88] 그는 이 설교에서 사랑, 인내, 자선, 자유 등 기독교의 핵심 가치의 영장성을 터치로 삼아 시민들에게 필요한 변화를 이끌어내기 위해 폭력보다는 하나님의 말씀을 신뢰하라고 일깨워줬다.[88]

Do you know what the Devil thinks when he sees men use violence to propagate the gospel?사람들이 복음을 전파하기 위해 폭력을 사용하는 것을 보면 악마가 어떻게 생각하는지 아십니까? He sits with folded arms behind the fire of hell, and says with malignant looks and frightful grin: "Ah, how wise these madmen are to play my game! 그는 지옥의 불 뒤에 팔짱을 끼고 앉아 악랄한 표정과 무서운 미소를 지으며 말한다: "아, 이 미친놈들이 내 게임을 하다니 얼마나 현명한가! Let them go on; I shall reap the benefit. 그들을 놓아 주어라. 나는 이익을 얻겠다. I delight in it." 나는 그것을 즐긴다고 말했다. But when he sees the Word running and contending alone on the battle-field, then he shudders and shakes for fear.[89] 그러나 그 말이 혼자서 전장에서 뛰고 다투는 것을 보면, 그는 무서워서 몸을 떨며 몸을 떨기도 한다.[89]

The effect of Luther's intervention was immediate.루터의 개입 효과는 즉각적이었다. After the sixth sermon, the Wittenberg jurist Jerome Schurf wrote to the elector: "Oh, what joy has Dr. Martin's return spread among us! 여섯 번째 설교가 끝난 후, 비텐베르크 법학자 제롬 슈르프는 선거인에게 이렇게 썼다: "아, 마틴 박사의 귀환이 우리 사이에 얼마나 기쁜 일이 퍼졌는가! His words, through divine mercy, are bringing back every day misguided people into the way of the truth."[89] 그의 말은, 신의 자비를 통해, 매일 잘못된 사람들을 진리의 길로 불러들이고 있다."[89]

Luther next set about reversing or modifying the new church practices.루터는 다음 번에 새로운 교회 관행을 바꾸거나 수정하기 시작했다. By working alongside the authorities to restore public order, he signalled his reinvention as a conservative force within the Reformation.[90] 공공질서를 회복하기 위해 당국과 함께 일함으로써, 그는 종교개혁 내의 보수세력으로서 그의 재창출을 의미했다.[90] After banishing the Zwickau prophets, he faced a battle against both the established Church and the radical reformers who threatened the new order by fomenting social unrest and violence.[91] 즈위카우 예언자들을 추방한 후, 그는 사회적 불안과 폭력을 조장함으로써 새로운 질서를 위협한 기성 교회와 급진적 개혁가 둘 다에 맞서 싸웠다.[91]

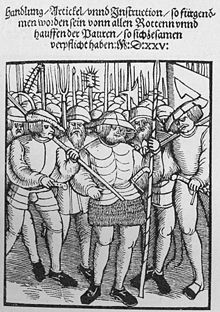

The Twelve Articles, 1525십이조항, 1525년

Despite his victory in Wittenberg, Luther was unable to stifle radicalism further afield.비텐베르크에서의 승리에도 불구하고 루터는 급진주의를 더 이상 억누를 수 없었다. Preachers such as Thomas Müntzer and Zwickau prophet Nicholas Storch found support amongst poorer townspeople and peasants between 1521 and 1525. 토마스 뮌처와 즈위카우 선지자 니콜라스 스토치와 같은 설교자들은 1521년에서 1525년 사이에 가난한 마을 사람들과 농민들 사이에서 지지를 얻었다. There had been revolts by the peasantry on smaller scales since the 15th century.[92] 15세기 이후 농민들의 소규모 반란이 있었다.[92] Luther's pamphlets against the Church and the hierarchy, often worded with "liberal" phraseology, led many peasants to believe he would support an attack on the upper classes in general.[93] 종종 "자유적"이라는 문구로 표현되는 루터의 교회와 계층에 대한 책자 때문에 많은 농민들은 그가 전반적으로 상류층에 대한 공격을 지지할 것이라고 믿게 되었다.[93] Revolts broke out in Franconia, Swabia, and Thuringia in 1524, even drawing support from disaffected nobles, many of whom were in debt. 1524년 프랑코니아, 스와비아, 튜링아에서 반란이 일어나 불만을 품은 귀족들의 지원까지 이끌어냈는데, 이들 중 다수는 빚을 지고 있었다. Gaining momentum under the leadership of radicals such as Müntzer in Thuringia, and Hipler and Lotzer in the south-west, the revolts turned into war.[94] 투링아의 뮌처, 남서부의 하이플러와 로처 등 급진파의 주도 아래 탄력이 붙으면서 반란군은 전쟁으로 변했다.[94]

Luther sympathised with some of the peasants' grievances, as he showed in his response to the Twelve Articles in May 1525, but he reminded the aggrieved to obey the temporal authorities.[95]루터는 1525년 5월 12조에 대한 대응에서 보듯이 농민들의 일부 불만을 동정했지만, 농민이 시간 당국에 복종하도록 상기시켰다.[95] During a tour of Thuringia, he became enraged at the widespread burning of convents, monasteries, bishops' palaces, and libraries. 튜링아를 여행하는 동안, 그는 수녀원, 수도원, 주교 궁전, 도서관이 널리 불타는 것에 격분했다. In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants, written on his return to Wittenberg, he gave his interpretation of the Gospel teaching on wealth, condemned the violence as the devil's work, and called for the nobles to put down the rebels like mad dogs: 그는 비텐베르크로 돌아오면서 쓴 <살인적이고 도둑질하는 소작농의 무리 반대>에서 복음서 가르침에 대한 해석을 내리고 폭력을 악마의 소행이라고 비난하며 귀족들에게 반역자들을 미친 개처럼 내려놓을 것을 요구했다.

Therefore let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel ...그러므로 반란군보다 더 독하고, 상처입고, 악마같은 것은 없다는 것을 기억하면서, 은밀하게든 공공연히든 할 수 있고, 때리고, 때리고, 때리고, 찌르고, 찌르고, 찌르고, 찌르고, 때리고, 찌르고, 찌르고, 때리고, 찌르고, 때리고, 찌 For baptism does not make men free in body and property, but in soul; and the gospel does not make goods common, except in the case of those who, of their own free will, do what the apostles and disciples did in Acts 4 [:32–37]. 세례는 사람을 육체와 재산에서 자유롭게 하는 것이 아니라 영혼에서 자유롭게 하는 것이 아니며, 복음은 재물을 보편적으로 만들지 않기 때문이다. 다만, 사도와 제자들이 4막에서 행한 대로 행하는 자의 경우는 예외로 한다 [:32–37]. They did not demand, as do our insane peasants in their raging, that the goods of others—of Pilate and Herod—should be common, but only their own goods. 그들은, 우리의 미친 소작농들이 격노하는 동안에 그러하듯이, 빌라도와 헤롯의 다른 사람의 재물은, 다만 자기들의 재물만이 되어야 한다고 요구하지 않았다. Our peasants, however, want to make the goods of other men common, and keep their own for themselves. 그러나 우리 농민들은 다른 사람의 재물을 흔하게 만들고, 스스로 자기 것을 지키고자 한다. Fine Christians they are! 훌륭한 기독교인들이야! I think there is not a devil left in hell; they have all gone into the peasants. 나는 지옥에 악마가 하나도 남아 있지 않다고 생각한다. 그들은 모두 소작농으로 들어갔다. Their raving has gone beyond all measure.[96] 그들의 야단법석은 이미 도를 넘었다.[96]

Luther justified his opposition to the rebels on three grounds.루터는 세 가지 이유로 반군에 대한 반대를 정당화했다. First, in choosing violence over lawful submission to the secular government, they were ignoring Christ's counsel to "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's"; St. Paul had written in his epistle to the Romans 13:1–7 that all authorities are appointed by God and therefore should not be resisted. 첫째로, 세속 정부에 대한 합법적인 복종보다 폭력을 선택하는데 있어서, 그들은 "시저에게 카이사르의 물건을 인도하라"는 그리스도의 권고를 무시하고 있었다; 성 바울은 로마인들에게 보낸 서간에서 모든 권위는 신에 의해 임명되므로 저항해서는 안 된다고 썼다. This reference from the Bible forms the foundation for the doctrine known as the divine right of kings, or, in the German case, the divine right of the princes. 성경에 나오는 이 언급은 왕들의 신권, 즉 독일의 경우 왕자들의 신권으로 알려진 교리의 기초를 형성한다. Second, the violent actions of rebelling, robbing, and plundering placed the peasants "outside the law of God and Empire", so they deserved "death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers." Lastly, Luther charged the rebels with blasphemy for calling themselves "Christian brethren" and committing their sinful acts under the banner of 둘째, 반역, 강탈, 약탈 등의 폭력적인 행위는 농민들을 '하나님과 제국의 법칙 밖'에 놓이게 했으므로, 그들은 '도로와 살인자일 뿐이라면 육체와 영혼의 죽음'을 당해야 마땅하다 마지막으로, 루터는 반군들을 '기독교 동포'라고 칭하고 죄업을 저질러 모독죄로 고발했다. the Gospel.[97]복음서[97] Only later in life did he develop the Beerwolf concept permitting some cases of resistance against the government.[98] 후에야 그는 정부에 대한 저항의 몇몇 사례를 허용하는 Beerwolf 개념을 발전시켰다.[98]

Without Luther's backing for the uprising, many rebels laid down their weapons; others felt betrayed.루터가 반란을 지지하지 않고 많은 반군들이 무기를 내려놓았고, 다른 반군들은 배신감을 느꼈다. Their defeat by the Swabian League at the Battle of Frankenhausen on 15 May 1525, followed by Müntzer's execution, brought the revolutionary stage of the Reformation to a close.[99] 1525년 5월 15일 프랑켄하우젠 전투에서 스와비안 연맹에 패한 데 이어 뮌처가 처형되면서 종교개혁의 혁명 무대가 막을 내렸다.[99] Thereafter, radicalism found a refuge in the Anabaptist movement and other religious movements, while Luther's Reformation flourished under the wing of the secular powers.[100] 이후 급진주의는 아나밥티스트 운동과 다른 종교 운동에서 피난처를 찾았고, 루터의 종교 개혁은 세속 세력의 휘하에서 번성했다.[100] In 1526 Luther wrote: "I, Martin Luther, have during the rebellion slain all the peasants, for it was I who ordered them to be struck dead."[101] 1526년에 루터는 다음과 같이 썼다. "나 마틴 루터는 반란 중에 모든 농민을 죽였다. 왜냐하면 그들을 죽이라고 명령한 것은 나였기 때문이다."[101]

Marriage결혼

Katharina von Bora, Luther's wife, by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 15261526년 장로 루터의 아내 카타리나 폰 보라

Martin Luther married Katharina von Bora, one of 12 nuns he had helped escape from the Nimbschen Cistercian convent in April 1523, when he arranged for them to be smuggled out in herring barrels.[102]마틴 루터는 1523년 4월 님셴 시스터치안 수녀원에서 탈출하는 데 도움을 준 12명의 수녀 중 한 명인 카타리나 폰 보라와 결혼했는데, 이때 그는 청어 통에 밀반출되도록 주선했다.[102] "Suddenly, and while I was occupied with far different thoughts," he wrote to Wenceslaus Link, "the Lord has plunged me into marriage."[103] 그는 웨슬로스 링크에게 "갑자기, 그리고 내가 전혀 다른 생각에 사로잡혀 있는 동안 주님이 나를 결혼에 빠뜨리셨다"[103]고 썼다. At the time of their marriage, Katharina was 26 years old and Luther was 41 years old. 결혼 당시 카타리나(Katharina)는 26세, 루터는 41세였다.

Martin Luther at his desk with family portraits (17th century)마틴 루터는 가족사진을 들고 책상에 앉아 있다(17세기)

On 13 June 1525, the couple was engaged, with Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Johannes Apel, Philipp Melanchthon and Lucas Cranach the Elder and his wife as witnesses.[104]1525년 6월 13일 이 부부는 요하네스 부겐하겐, 쥐스투스 요나스, 요하네스 아펠, 필리프 멜랑숑, 장로 루카스 크랜라크와 그의 부인과 함께 증인으로 약혼했다.[104] On the evening of the same day, the couple was married by Bugenhagen.[104] 이날 저녁 이 부부는 부겐하겐이 결혼했다.[104] The ceremonial walk to the church and the wedding banquet were left out and were made up two weeks later on 27 June.[104] 교회로 가는 의례적인 산책과 결혼 피로연은 생략되었고 2주 후인 6월 27일에 화해되었다.[104]

Some priests and former members of religious orders had already married, including Andreas Karlstadt and Justus Jonas, but Luther's wedding set the seal of approval on clerical marriage.[105]안드레아스 칼슈타트, 저스투스 요나스 등 일부 성직자와 전 종교질서의 구성원들은 이미 결혼했으나 루터의 결혼식은 성직자의 결혼에 찬성의 도장을 찍었다.[105] He had long condemned vows of celibacy on Biblical grounds, but his decision to marry surprised many, not least Melanchthon, who called it reckless.[106] 그는 오랫동안 성경적 이유로 독신 서약을 비난해 왔지만, 결혼하기로 한 그의 결정은 그것을 무모하다고 말한 멜랑숑을 비롯한 많은 사람들을 놀라게 했다.[106] Luther had written to George Spalatin on 30 November 1524, "I shall never take a wife, as I feel at present. 루터는 1524년 11월 30일 조지 스팔라틴에게 편지를 썼다. "나는 현재 내가 느끼고 있는 것처럼 결코 아내를 데려가지 않을 것이다. Not that I am insensible to my flesh or sex (for I am neither wood nor stone); but my mind is averse to wedlock because I daily expect the death of a heretic."[107] 내가 내 살이나 성에 대해 무감각하다는 것은 아니다. 그러나 내 마음은 매일 이단자의 죽음을 예상하기 때문에 결혼하는 것을 싫어한다.'[107] Before marrying, Luther had been living on the plainest food, and, as he admitted himself, his mildewed bed was not properly made for months at a time.[108] 결혼하기 전에 루터는 가장 담백한 음식으로 살아왔으며, 자신을 인정했듯이 순한 침대는 한 번에 몇 달 동안 제대로 만들어지지 않았다.[108]

Luther and his wife moved into a former monastery, "The Black Cloister," a wedding present from Elector John the Steadfast.루터와 그의 아내는 스테드펀트인 요한 일렉터로부터 받은 결혼 선물인 "검은 클루스터"라는 전직 수도원으로 이사했다. They embarked on what appears to have been a happy and successful marriage, though money was often short.[109] 그들은 비록 돈이 종종 부족했지만, 행복하고 성공적인 결혼 생활을 시작했다.[109] Katharina bore six children: 카타리나에는 6명의 아이가 있었다. Hans – June 1526; Elizabeth – 10 December 1527, who died within a few months; Magdalene – 1529, who died in Luther's arms in 1542; Martin – 1531; Paul – January 1533; and Margaret – 1534; and she helped the couple earn a living by farming and taking in boarders.[110] 한스 – 1526년 6월, 엘리자베스 – 1527년 12월 10일, 몇 달 안에 죽은 사람, 1542년 루터의 품에서 죽은 막달렌 – 1529년, 마틴 – 1531년, 폴 – 1533년 1월, 마거릿 – 1534년, 그리고 그녀는 농사와 하숙인들로 생계를 꾸려나가는데 일조했다.[110] Luther confided to Michael Stiefel on 11 August 1526: "My Katie is in all things so obliging and pleasing to me that I would not exchange my poverty for the riches of Croesus."[111] 루터는 1526년 8월 11일 마이클 스티펠에게 "나의 케이티는 모든 일에 있어서 나의 가난을 크로우소스의 부와 바꾸지 않을 만큼 나에게 친절하고 즐겁게 해주고 있다"[111]고 털어놓았다.

Organising the church교회 조직

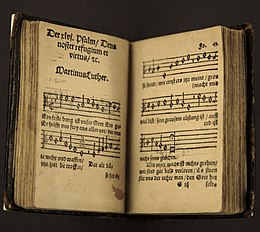

Church orders, Mecklenburg 1650교회령, 메클렌부르크 1650

By 1526, Luther found himself increasingly occupied in organising a new church.1526년까지 루터는 새로운 교회를 조직하는데 점점 더 몰두하고 있는 자신을 발견했다. His Biblical ideal of congregations choosing their own ministers had proved unworkable.[112] 그의 성서적 이상인 회중들이 그들 자신의 목사들을 고르는 것은 실행 불가능한 것으로 판명되었다.[112] According to Bainton: "Luther's dilemma was that he wanted both a confessional church based on personal faith and experience and a territorial church including all in a given locality. 베인턴은 "루더의 딜레마는 개인적인 믿음과 경험에 근거한 고백성 교회와 주어진 지역성에 있는 모든 것을 포함한 영토성 교회 모두를 원한다는 것이었다"고 전했다. If he were forced to choose, he would take his stand with the masses, and this was the direction in which he moved."[113] 어쩔 수 없이 선택한다면 대중들과 함께 자신의 입장을 취할 것이고, 이것이 그가 움직이는 방향이었습니다."[113]

From 1525 to 1529, he established a supervisory church body, laid down a new form of worship service, and wrote a clear summary of the new faith in the form of two catechisms.[114]1525년부터 1529년까지 감독 교회 단체를 설립하여 새로운 형태의 예배를 드리우고, 새로운 신앙을 두 개의 교리문양식으로 명료하게 요약하여 썼다.[114] To avoid confusing or upsetting the people, Luther avoided extreme change. 루터는 국민을 혼란시키거나 화나게 하지 않기 위해 극단적인 변화를 피했다. He also did not wish to replace one controlling system with another. 그는 또한 한 제어 시스템을 다른 제어 시스템으로 교체하기를 원하지 않았다. He concentrated on the church in the Electorate of Saxony, acting only as an adviser to churches in new territories, many of which followed his Saxon model. 그는 작센 선거구의 교회에 집중하여, 새로운 영토의 교회들의 조언자 역할만 하였는데, 그 중 다수는 그의 작센 모델을 따랐다. He worked closely with the new elector, John the Steadfast, to whom he turned for secular leadership and funds on behalf of a church largely shorn of its assets and income after the break with Rome.[115] 그는 새로운 당선자인 스테드패스트 요한과 긴밀하게 일했고, 그는 로마와의 휴식 후 대부분 그 자산과 수입을 탈피한 교회를 대신하여 세속적인 지도력과 자금을 지원했다.[115] For Luther's biographer Martin Brecht, this partnership "was the beginning of a questionable and originally unintended development towards a church government under the temporal sovereign".[116] 루터의 전기 작가 마틴 브레히트에게 이 파트너십은 "시간적 주권 하에서 교회 정부를 향한 의심스럽고 원래 의도하지 않은 발전의 시작이었다"고 말했다.[116]

The elector authorised a visitation of the church, a power formerly exercised by bishops.[117]선출자는 이전에 주교들이 행사했던 힘인 교회의 방문을 승인했다.[117] At times, Luther's practical reforms fell short of his earlier radical pronouncements. 때때로 루터의 실질적인 개혁은 그의 초기 급진적인 선언에 미치지 못했다. For example, the Instructions for the Visitors of Parish Pastors in Electoral Saxony (1528), drafted by Melanchthon with Luther's approval, stressed the role of repentance in the forgiveness of sins, despite Luther's position that faith alone ensures justification.[118] 예를 들어 멜랑크톤이 루터의 승인을 얻어 초안한 선거 색슨 교구 목회자 방문지침(1528년)은 믿음만으로도 정당성이 보장된다는 루터의 입장에도 불구하고 죄의 용서에 대한 회개의 역할을 강조했다.[118] The Eisleben reformer Johannes Agricola challenged this compromise, and Luther condemned him for teaching that faith is separate from works.[119] 아이슬레벤 개혁가 요하네스 아그리콜라는 이 타협에 도전했고, 루터는 신앙은 일과 별개라는 것을 가르친다고 그를 비난했다.[119] The Instruction is a problematic document for those seeking a consistent evolution in Luther's thought and practice.[120] 그 지시는 루터의 사고와 실천에서 일관된 진화를 추구하는 사람들에게 문제가 되는 문서다.[120]

Lutheran church liturgy and sacraments루터교회의 예배와 성찬.

In response to demands for a German liturgy, Luther wrote a German Mass, which he published in early 1526.[121]독일인의 소송에 대한 요구에 대응하여 루터는 1526년 초에 발표한 독일 미사를 썼다.[121] He did not intend it as a replacement for his 1523 adaptation of the Latin Mass but as an alternative for the "simple people", a "public stimulation for people to believe and become Christians."[122] 그는 자신이 1523년 라틴미사를 각색한 것을 대체하기 위한 것이 아니라 '단순한 민족'을 위한 대안으로 '사람들이 믿고 기독교인이 되기 위한 대중적 자극'을 의도했다.[122] Luther based his order on the Catholic service but omitted "everything that smacks of sacrifice", and the Mass became a celebration where everyone received the wine as well as the bread.[123] 루터는 가톨릭 예배에 근거해 자신의 명령을 내렸으나 '희생하는 냄새가 나는 모든 것'을 생략했고, 미사는 빵뿐만 아니라 모두가 포도주를 받는 축전이 되었다.[123] He retained the elevation of the host and chalice, while trappings such as the Mass vestments, altar, and candles were made optional, allowing freedom of ceremony.[124] 그는 숙주와 샬리스를 높이 유지했고, 미사 조끼, 제단, 촛불 등의 위패는 선택적으로 만들어 의례의 자유를 허용했다.[124] Some reformers, including followers of Huldrych Zwingli, considered Luther's service too papistic, and modern scholars note the conservatism of his alternative to the Catholic mass.[125] 헐리치 즈윙글리 추종자들을 포함한 일부 개혁론자들은 루터의 봉사를 너무 교황주의적이라고 생각했고, 현대 학자들은 루터가 가톨릭 미사에 대한 대안인 보수주의에 주목한다.[125] Luther's service, however, included congregational singing of hymns and psalms in German, as well as parts of the liturgy, including Luther's unison setting of the Creed.[126] 그러나 루터의 예배에는 독일어로 찬송가와 찬송가를 합창하는 것은 물론, 루터의 일치된 신조 설정 등 공론의 일부도 포함되었다.[126] To reach the simple people and the young, Luther incorporated religious instruction into the weekday services in the form of the catechism.[127] 소박한 사람들과 젊은이들에게 다가가기 위해 루터는 종교적인 가르침을 교리주의의 형태로 평일 예배에 접목시켰다.[127] He also provided simplified versions of the baptism and marriage services.[128] 그는 또한 세례와 결혼 예배의 간결한 버전을 제공했다.[128]

Luther and his colleagues introduced the new order of worship during their visitation of the Electorate of Saxony, which began in 1527.[129]루터와 그의 동료들은 1527년에 시작된 작센 선거구의 방문 동안 새로운 예배 질서를 소개했다.[129] They also assessed the standard of pastoral care and Christian education in the territory. 이들은 이 지역에서 목회자 돌봄과 기독교 교육의 수준도 평가했다. "Merciful God, what misery I have seen," Luther writes, "the common people knowing nothing at all of Christian doctrine ... and unfortunately many pastors are well-nigh unskilled and incapable of teaching."[130] 루터는 "진정한 하나님, 내가 본 참담함"이라며 "평민들은 기독교 교리에 대해 전혀 알지 못하며 불행히도 많은 목회자들은 잘 알지 못하고 가르칠 능력이 없다"[130]고 썼다.

Catechisms카테키즘

A stained glass portrayal of Luther루터의 스테인드글라스 묘사

Luther devised the catechism as a method of imparting the basics of Christianity to the congregations.루터는 기독교의 기본을 교리에 전하기 위한 방법으로 교리학을 고안했다. In 1529, he wrote the Large Catechism, a manual for pastors and teachers, as well as a synopsis, the Small Catechism, to be memorised by the people.[131] 1529년에는 목회자와 교사를 위한 매뉴얼인 '대(大)[131]카테치즘'과 함께 '작은카테치즘'이라는 시놉시스를 써서 국민에게 암기했다. The catechisms provided easy-to-understand instructional and devotional material on the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, The Lord's Prayer, baptism, and the Lord's Supper.[132] 교리문제는 십계명, 사도신조, 주기도, 세례, 주기도회 등에 대한 이해하기 쉬운 가르침과 일탈적 자료를 제공했다.[132] Luther incorporated questions and answers in the catechism so that the basics of Christian faith would not just be learned by rote, "the way monkeys do it", but understood.[133] 루터는 기독교 신앙의 기본이 단순히 '원숭이가 하는 방식'으로 배우지 않고 이해되도록 교리학에 문답을 통합했다.[133]

The catechism is one of Luther's most personal works.교리주의는 루터의 가장 개인적인 작품 중 하나이다. "Regarding the plan to collect my writings in volumes," he wrote, "I am quite cool and not at all eager about it because, roused by a Saturnian hunger, I would rather see them all devoured. 그는 "내 글들을 대량으로 수집하려는 계획에 대해 나는 토성의 배고픔에 자극되어 그들이 모두 먹어치우는 것을 보고 싶어하기 때문에 나는 꽤 멋지고 전혀 열의가 없다"고 썼다. For I acknowledge none of them to be really a book of mine, except perhaps the Bondage of the Will and the Catechism."[134] 나는 그들 중 어느 누구도 진정한 나의 책이라고 인정하지 않고, 어쩌면 유언의 본디지와 카테키즘을 제외하고는."[134] The Small Catechism has earned a reputation as a model of clear religious teaching.[135] 스몰 카테키즘은 명확한 종교적 가르침의 모범으로 명성을 얻었다.[135] It remains in use today, along with Luther's hymns and his translation of the Bible. 루터의 찬송가, 그의 성경 번역과 함께 오늘날에도 사용되고 있다.

Luther's Small Catechism proved especially effective in helping parents teach their children; likewise the Large Catechism was effective for pastors.[136]루터의 작은 교리주의는 부모들이 자녀들을 가르치는 것을 돕는데 특히 효과적임이 입증되었다; 마찬가지로 목회자들에게도 큰 교리 교리가 효과적이었다.[136] Using the German vernacular, they expressed the Apostles' Creed in simpler, more personal, Trinitarian language. 그들은 독일어를 사용하여 사도들의 신조를 보다 단순하고 개인적인 삼위일체적인 언어로 표현했다. He rewrote each article of the Creed to express the character of the Father, the Son, or the Holy Spirit. 그는 신조의 각 글을 다시 써서 성부와 성자 또는 성령의 성격을 표현했다. Luther's goal was to enable the catechumens to see themselves as a personal object of the work of the three persons of the Trinity, each of which works in the catechumen's life.[137] 루터의 목표는 카테쿠멘이 스스로를 카테쿠멘의 삶에서 각각 작용하는 삼위일체 세 사람의 작품의 개인적 대상으로 볼 수 있게 하는 것이었다.[137] That is, Luther depicts the Trinity not as a doctrine to be learned, but as persons to be known. 즉, 루터는 삼위일체를 학습할 교리가 아니라 알 수 있는 사람으로 묘사한다. The Father creates, the Son redeems, and the Spirit sanctifies, a divine unity with separate personalities. 아버지는 창조하시고, 아들은 구원하시고, 영은 성령을 거룩하게 하십니다. 이는 분리된 인격으로 이루어진 신성한 통합입니다. Salvation originates with the Father and draws the believer to the Father. 구원은 아버지로부터 시작되어 신자를 아버지께 끌어 당긴다. Luther's treatment of the Apostles' Creed must be understood in the context of the Decalogue (the Ten Commandments) and The Lord's Prayer, which are also part of the Lutheran catechetical teaching.[137] 루터의 사도신조에 대한 대우는 루터의 교리교육의 일환이기도 한 데카로그(십계명)와 주기도의 맥락에서 이해되어야 한다.[137]

Translation of the Bible성경의 번역

Main article:주요 기사: Luther Bible 루터 성경

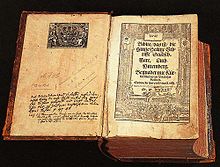

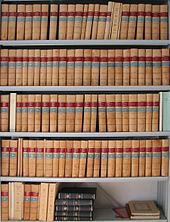

Luther's 1534 Bible루터의 1534년 성경

Luther had published his German translation of the New Testament in 1522, and he and his collaborators completed the translation of the Old Testament in 1534, when the whole Bible was published.루터는 1522년에 신약성경의 독일어 번역을 출판했고, 그와 그의 협력자들은 1534년에 구약성경의 번역을 완성했는데, 이때 성경 전체가 출판되었다. He continued to work on refining the translation until the end of his life.[138] 그는 생전까지 번역을 다듬는 작업을 계속했다.[138] Others had previously translated the Bible into German, but Luther tailored his translation to his own doctrine.[139] 다른 사람들은 이전에 성경을 독일어로 번역한 적이 있었지만, 루터는 자신의 번역에 자신의 교리에 맞추었다.[139] Two of the earlier translations were the Mentelin Bible (1456)[140] and the Koberger Bible (1484).[141] 초기 번역본 중 두 편이 멘텔린 성경(1456)[140]과 코베르거 성경(1484)이었다.[141] There were as many as fourteen in High German, four in Low German, four in Dutch, and various other translations in other languages before the Bible of Luther.[142] 루터의 성경 이전에는 고독일어 14개, 저독일어 4개, 네덜란드어 4개, 기타 여러 언어로 번역된 번역본이 있었다.[142]

Luther's translation used the variant of German spoken at the Saxon chancellery, intelligible to both northern and southern Germans.[143]루터의 번역은 색슨족 찬스텔러리에서 사용되는 독일어의 변형을 사용했는데, 북독인과 남독인이 모두 이해할 수 있다.[143] He intended his vigorous, direct language to make the Bible accessible to everyday Germans, "for we are removing impediments and difficulties so that other people may read it without hindrance."[144] 그는 "우리는 장애물과 어려움을 제거하여 다른 사람들이 방해받지 않고 성경을 읽을 수 있도록 하기 때문에" 성경을 일상 독일인들이 접할 수 있도록 힘차고 직접적인 언어를 사용하고자 했다.[144] Published at a time of rising demand for German-language publications, Luther's version quickly became a popular and influential Bible translation. 독일어 출판물에 대한 수요가 증가하는 시기에 출판된 루터의 버전은 빠르게 인기 있고 영향력 있는 성경 번역본이 되었다. As such, it contributed a distinct flavor to German language and literature.[145] 그만큼 독일어와 문학에 뚜렷한 풍미를 기여했다.[145] Furnished with notes and prefaces by Luther, and with woodcuts by Lucas Cranach that contained anti-papal imagery, it played a major role in the spread of Luther's doctrine throughout Germany.[146] 루터에 의해 노트와 프리페이스를 비치하고, 루카스 크랜라크의 반파적 이미지가 담긴 목판화로 독일 전역으로 루터의 교리가 전파되는 데 큰 역할을 했다.[146] The Luther Bible influenced other vernacular translations, such as the Tyndale Bible (from 1525 forward), a precursor of the King James Bible.[147] 루터 성경은 킹 제임스 성경의 선구자인 틴데일 성경과 같은 다른 자국어 번역에 영향을 주었다.[147]

When he was criticised for inserting the word "alone" after "faith" in Romans 3:28,[148] he replied in part: "[T]he text itself and the meaning of St. Paul urgently require and demand it.로마서 3장 28절에서 '신앙' 뒤에 '혼자'라는 단어를 삽입했다는 비판을 받자, 그는 부분적으로 '[T]그는 문자 그 자체와 성 바울의 뜻이 긴급히 요구하고 요구한다고 대답했다.[148] For in that very passage he is dealing with the main point of Christian doctrine, namely, that we are justified by faith in Christ without any works of the Law. ... 바로 그 대목에서 그는 기독교 교리의 요점, 즉 우리가 율법의 아무런 업적도 없이 그리스도에 대한 믿음으로 정당화될 수 있다는 것을 다루고 있기 때문이다... But when works are so completely cut away—and that must mean that faith alone justifies—whoever would speak plainly and clearly about this cutting away of works will have to say, 'Faith alone justifies us, and not works'."[149] 그러나 일이 그렇게 완전히 잘려나가고, 그 말은 믿음만이 정당화한다는 뜻임에 틀림없어. 이 일을 잘라내는 일에 대해 누구라도 솔직하고 분명하게 말할 사람은 '신앙만이 우리를 정당화하며, 일하지 않는다'고 말할 수 밖에 없을 것이다.[149] Luther did not include First Epistle of John 5:7–8,[150] the Johannine Comma in his translation, rejecting it as a forgery. 루터는 요한나인 콤마 [150]5장 7절-8절의 첫 경문을 번역문에 포함시키지 않고 위작이라고 거절했다. It was inserted into the text by other hands after Luther's death.[151][152] 루터가 죽은 후 다른 손에 의해 본문에 삽입되었다.[151][152]

HymnodistHymnodist

Main article:주요 기사: List of hymns by Martin Luther 마틴 루터의 찬송가 목록

An early printing of Luther's hymn "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott"루터의 찬송가 "Ein feste Burg is unser Gott"의 초기 인쇄

|

|

Ein feste Burg sung in German독일어로 부른 아인 페스트 버거

Menu

0:00

The German text of "Ein feste Burg" ("A Mighty Fortress") sung to the isometric, more widely known arrangement of its traditional melody독일어로 된 "Ein feste Burg" ("A Mighty Forture")는 전통적인 멜로디의 편곡으로 더 널리 알려진 등축에 맞추어 노래했다. |

| Problems playing this file?이 파일을 재생하는 데 문제가 있으십니까? See media help. 미디어 도움말을 참조하십시오. | |

Luther was a prolific hymnodist, authoring hymns such as "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" ("A Mighty Fortress Is Our God"), based on Psalm 46, and "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" ("From Heaven Above to Earth I Come"), based on Luke 2:11–12.[153]루터는 시편 46편을 원작으로 한 "Ein Feste Burg ist unser Gott"("A Mighty Status Is Our Gott")와 루크 2:11–12를 원작으로 한 "Vom Himmel hoch, da Komm ir"("Vom Himel Hoch, Da Comm I Come")와 같은 찬송가를 작곡한 다작곡가였다.[153] Luther connected high art and folk music, also all classes, clergy and laity, men, women and children. 루터는 높은 예술과 민속 음악, 또한 모든 계급, 성직자와 평신도, 남자, 여자, 어린이들을 연결시켰다. His tool of choice for this connection was the singing of German hymns in connection with worship, school, home, and the public arena.[154] 이러한 연계를 위해 그가 선택한 도구는 예배, 학교, 가정, 공공장소와 관련하여 독일 찬송가를 부르는 것이었다.[154] He often accompanied the sung hymns with a lute, later recreated as the waldzither that became a national instrument of Germany in the 20th century.[155] 그는 20세기에 독일의 국가 악기가 된 왈츠데르로 재탄생한 루트와 함께 성찬을 자주 동행했다.[155]

Luther's hymns were frequently evoked by particular events in his life and the unfolding Reformation.루터의 찬송가는 그의 삶에서 일어나는 특별한 사건들과 전개되는 종교개혁에 의해 자주 환기되었다. This behavior started with his learning of the execution of Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos, the first individuals to be martyred by the Roman Catholic Church for Lutheran views, prompting Luther to write the hymn "Ein neues Lied wir heben an" ("A new song we raise"), which is generally known in English by John C. 이러한 행동은 로마 가톨릭교회가 루터의 견해를 위해 순교한 최초의 개인인 얀 반 에센과 헨드릭 보스의 처형을 알게 되면서 시작되었는데, 루터는 존 C에 의해 일반적으로 영어로 알려진 찬송가 "Ein nees Lied Wir heben an"을 쓰게 되었다. Messenger's translation by the title and first line "Flung to the Heedless Winds" and sung to the tune Ibstone composed in 1875 by Maria C. 제목과 첫 줄에 의한 메신저 번역 "Flung to the Heedless Winds" 그리고 마리아 C가 1875년에 작곡한 이브스톤에 맞추어 노래했다. Tiddeman.[156] 티드먼.[156]

Luther's 1524 creedal hymn "Wir glauben all an einen Gott" ("We All Believe in One True God") is a three-stanza confession of faith prefiguring Luther's 1529 three-part explanation of the Apostles' Creed in the Small Catechism.루터의 1524년 신조 찬송가 "Wir all a einen Gott"(We All Believe in One True Godt)는 루터의 1529년 소교도에 대한 사도들의 신조에 대한 3부 설명을 사전 구성하여 신앙을 고백한 것이다. Luther's hymn, adapted and expanded from an earlier German creedal hymn, gained widespread use in vernacular Lutheran liturgies as early as 1525. 루터의 찬송가는 독일의 초기 신조 찬송가에서 각색되고 확장되었으며, 1525년경부터 자국어 루터교의 찬송가에서 널리 쓰이게 되었다. Sixteenth-century Lutheran hymnals also included "Wir glauben all" among the catechetical hymns, although 18th-century hymnals tended to label the hymn as Trinitarian rather than catechetical, and 20th-century Lutherans rarely used the hymn because of the perceived difficulty of its tune.[154] 16세기 루터 찬송가 역시 교미 찬송가 가운데 '위르 글라우벤 올(Wir gloosen all)'을 포함시켰는데, 18세기 찬송가는 교미보다는 삼위일체(Trinistic)로 표기하는 경향이 있었고, 20세기 루터인들은 그 가락의 난이도를 인지하여 찬송가를 거의 사용하지 않았다.[154]

.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{display:flex;flex-direction:column}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{display:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{margin:1px;float:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theader{clear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-left{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-right{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-center{text-align:center}@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{justify-content:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle .thumbcaption{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow>.thumbcaption{text-align:center}}

Autograph of "Vater unser im Himmelreich", with the only notes extant in Luther's handwriting루터의 필적에 유일하게 남아 있는 "Vater unser Im Himmelreich"의 사인

Luther's 1538 hymnic version of the Lord's Prayer, "Vater unser im Himmelreich", corresponds exactly to Luther's explanation of the prayer in the Small Catechism, with one stanza for each of the seven prayer petitions, plus opening and closing stanzas.루터가 1538년에 쓴 주기도서의 극본인 "성자 운서자 임 히멜레이히"는 루터가 작은 카테키즘에서 기도하는 것에 대한 설명과 정확히 일치하며, 7개의 기도 청원 각각에 1개의 스탠자를 더하고, 개폐 스탠자를 더한다. The hymn functions both as a liturgical setting of the Lord's Prayer and as a means of examining candidates on specific catechism questions. 찬송가는 주기도의 소송 설정과 특정 교리학 문제에 대한 후보자들의 심사를 위한 수단으로 모두 기능한다. The extant manuscript shows multiple revisions, demonstrating Luther's concern to clarify and strengthen the text and to provide an appropriately prayerful tune. 현존하는 원고는 복수의 수정본을 보여주며, 본문을 명확히 하고 강화하며 적절히 기도적인 곡조를 제공하려는 루터의 우려를 증명한다. Other 16th- and 20th-century versifications of the Lord's Prayer have adopted Luther's tune, although modern texts are considerably shorter.[157] 다른 16세기와 20세기 주기도서의 판화는 현대의 문헌은 상당히 짧지만 루터의 곡조를 채택했다.[157]

Luther wrote "Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir" ("From depths of woe I cry to You") in 1523 as a hymnic version of Psalm 130 and sent it as a sample to encourage his colleagues to write psalm-hymns for use in German worship.루터는 1523년 시편 130편의 찬송가로 "Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir"("내가 당신에게 우는 깊은 슬픔에서")를 썼고 이를 샘플로 보내 동료들이 독일 예배에서 사용할 찬송가를 쓰도록 격려했다. In a collaboration with Paul Speratus, this and seven other hymns were published in the Achtliederbuch, the first Lutheran hymnal. Paul Speratus와 협력하여, 이것과 7개의 다른 찬송가가 최초의 루터교의 찬송가인 Achtyderbuch에 발표되었다. In 1524 Luther developed his original four-stanza psalm paraphrase into a five-stanza Reformation hymn that developed the theme of "grace alone" more fully. 1524년 루터는 자신의 원래 4성 시편 시편을 5성 시편 종교개혁 찬송가로 발전시켜 '홀로 은혜'라는 주제를 더욱 완전하게 발전시켰다. Because it expressed essential Reformation doctrine, this expanded version of "Aus tiefer Not" was designated as a regular component of several regional Lutheran liturgies and was widely used at funerals, including Luther's own. 그것이 본질적인 종교개혁 교리를 표현했기 때문에, 이 확장된 버전의 "Aus tiefer Not"은 몇몇 지역 루터 재판소의 규칙적인 구성 요소로 지정되었고 루터 자신의 것을 포함한 장례식에서 널리 사용되었다. Along with Erhart Hegenwalt's hymnic version of Psalm 51, Luther's expanded hymn was also adopted for use with the fifth part of Luther's catechism, concerning confession.[158] 에르하르트 헤겐왈트의 극본 시편 51편과 함께 루터의 확장 찬송가도 루터의 교리교 5부 고해성사에 관한 용도로 채택되었다.[158]

Luther wrote "Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein" ("Oh God, look down from heaven").루터는 "Ach Gott, Himmel sie darlin" ("오 하느님, 하늘에서 내려다보십시오. "Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland" (Now come, Savior of the gentiles), based on Veni redemptor gentium, became the main hymn (Hauptlied) for Advent. "Nunkomm, der Heiden Hilleland" (이제 와라, 젠틀맨의 구세주)는 베네딕토르 젠티움을 원작으로 하여, 재림절의 주요 찬송가(Haupty)가 되었다. He transformed A solus ortus cardine to "Christum wir sollen loben schon" ("We should now praise Christ") and Veni Creator Spiritus to "Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist" ("Come, Holy Spirit, Lord God").[159] 그는 A 솔러스 오르투스 카딘을 "크리스툼 위르 솔렌 로브 션"("우리는 이제 그리스도를 찬양해야 한다")으로, 베니 크리에이터 스피리투스를 "콤, 고트 숄퍼, 헤이리거 가이스트"("성령, 주 하나님")로 변형시켰다.[159] He wrote two hymns on the Ten Commandments, "Dies sind die heilgen Zehn Gebot" and "Mensch, willst du leben seliglich". 그는 십계명에 "Dies sind die hilegen Zehn Gebot"과 "Mensch, willst du leben seliglich"라는 두 개의 찬송가를 썼다. His "Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ" ("Praise be to You, Jesus Christ") became the main hymn for Christmas. 그의 "Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ" ("Praise be to You, Jesus Christ")는 크리스마스의 주요 찬송가가 되었다. He wrote for Pentecost "Nun bitten wir den Heiligen Geist", and adopted for Easter "Christ ist erstanden" (Christ is risen), based on Victimae paschali laudes. 그는 펜테코스트 "Nun wird den Hileigen Geist"에 글을 썼고, 희생자에 파스칼리 찬송을 바탕으로 부활절에 "Christ ist erstanden"(기독교는 부활했다)에 채택되었다. "Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin", a paraphrase of Nunc dimittis, was intended for Purification, but became also a funeral hymn. Nunc dimittis의 비유인 "Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin"은 "정화"를 위한 것이었지만, 장례 찬송가가 되기도 했다. He paraphrased the Te Deum as "Herr Gott, dich loben wir" with a simplified form of the melody. 그는 테 디움을 단순화된 형태의 멜로디로 "Herr Gott, dich loben wir"로 표현했다. It became known as the German Te Deum. 그것은 독일 테 디움으로 알려지게 되었다.

Luther's 1541 hymn "Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam" ("To Jordan came the Christ our Lord") reflects the structure and substance of his questions and answers concerning baptism in the Small Catechism.루터의 1541년 찬송가 "Herr zum Jordan kam"("요르단이 우리 주 그리스도께로 왔다")는 작은 카테키즘의 세례에 관한 그의 질문과 대답의 구조와 실체를 반영한다. Luther adopted a preexisting Johann Walter tune associated with a hymnic setting of Psalm 67's prayer for grace; Wolf Heintz's four-part setting of the hymn was used to introduce the Lutheran Reformation in Halle in 1541. 루터는 시편 67편의 은총을 기원하는 극악무도한 설정과 연관된 현존하는 요한 발터 가락을 채택했다; 울프 하인츠의 찬송가 4부 설정은 1541년 할레에서 루터교화를 도입하는 데 사용되었다. Preachers and composers of the 18th century, including J.S. Bach, used this rich hymn as a subject for their own work, although its objective baptismal theology was displaced by more subjective hymns under the influence of late-19th-century Lutheran pietism.[154] J.S. 바흐를 비롯한 18세기의 설교자들과 작곡가들은 비록 객관적 세례신학이 19세기 말 루터 페티즘의 영향을 받아 보다 주관적인 찬송가에 의해 대체되었음에도 불구하고 이 풍부한 찬송가를 자신들의 작품의 소재로 삼았다.[154]

Luther's hymns were included in early Lutheran hymnals and spread the ideas of the Reformation.초기 루터의 찬송가에는 루터의 찬송가가 포함되었고 종교개혁의 사상을 전파하였다. He supplied four of eight songs of the First Lutheran hymnal Achtliederbuch, 18 of 26 songs of the Erfurt Enchiridion, and 24 of the 32 songs in the first choral hymnal with settings by Johann Walter, Eyn geystlich Gesangk Buchleyn, all published in 1524. 1524년에 발표된 제1루터 히메날 아치티데르부흐의 8곡 중 4곡, 에르푸르트 앙치리디온의 26곡 중 18곡, 제1합창의 32곡 중 24곡을 요한 발터, 아이언 게스틀리히 게상크 부클린의 설정으로 공급하였다. Luther's hymns inspired composers to write music. 루터의 찬송가는 작곡가들이 음악을 쓰도록 영감을 주었다. Johann Sebastian Bach included several verses as chorales in his cantatas and based chorale cantatas entirely on them, namely Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4, as early as possibly 1707, in his second annual cycle (1724 to 1725) Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein, BWV 2, Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam, BWV 7, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 62, Johann Sebastian Bach included several verses as chorales in his cantatas and based chorale cantatas entirely on them, namely Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4, as early as possibly 1707, in his second annual cycle (1724 to 1725) Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein, BWV 2, Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam, BWV 7, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 62, Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 91, and Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, BWV 38, later Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80, and in 1735 Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit, BWV 14. Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 91, Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, BWV 38, 나중에 Ein feste Burg is unser Gott, BWV 80, 1735년 Wér Gott nicht nuns die Zeit, BWV 14.

On the soul after death사후 영혼에

Luther on the left with Lazarus being raised by Jesus from the dead, painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1558왼쪽의 루터, 1558년 루카스 크랜라크 장로가 그린 라자루스와 함께 죽은 사람으로부터 예수님이 기른 레자루스가 있다.

In contrast to the views of John Calvin[160] and Philipp Melanchthon,[161] throughout his life Luther maintained that it was not false doctrine to believe that a Christian's soul sleeps after it is separated from the body in death.[162]존 캘빈과[160] 필립 멜랑숑의 견해와는 대조적으로,[161] 루터는 일생 동안 기독교인의 영혼이 죽음에서 육체와 분리된 후에 잠을 잔다고 믿는 것은 잘못된 교리가 아니라고 주장했다.[162] Accordingly, he disputed traditional interpretations of some Bible passages, such as the parable of the rich man and Lazarus.[163] 이에 따라 그는 부자와 레자로스의 비유와 같은 일부 성경 구절에 대한 전통적인 해석에 대해 논쟁을 벌였다.[163] This also led Luther to reject the idea of torments for the saints: "It is enough for us to know that souls do not leave their bodies to be threatened by the torments and punishments of hell, but enter a prepared bedchamber in which they sleep in peace."[164] 이 때문에 루터는 "영혼은 지옥의 고뇌와 형벌에 의해 위협받기 위해 자신의 몸을 떠나지 않고, 그들이 편히 잠드는 준비된 침실로 들어가는 것으로 충분하다"[164]는 성도들의 고뇌에 대한 생각을 거부하게 되었다. He also rejected the existence of purgatory, which involved Christian souls undergoing penitential suffering after death.[165] 그는 또한 사후에 참회하는 고통을 겪고 있는 기독교 영혼들이 관련된 연옥의 존재를 거부했다.[165] He affirmed the continuity of one's personal identity beyond death. 그는 죽음을 넘어서는 개인의 정체성의 연속성을 단언했다. In his Smalcald Articles, he described the saints as currently residing "in their graves and in heaven."[166] 그는 스말칼드 기고문에서 성도들이 현재 "그들의 무덤과 천국에 살고 있다"[166]고 묘사했다.