진핵생물

| Eukaryotes 및 그들의 다양성의 몇 가지 예 - 왼쪽 상단에서 시계 방향으로 : 레드 메이슨 벌, 볼레투스 에둘리스, 침팬지, 이소 트리카 창자, 라뉘쿨러스 아시아티쿠스 및 볼복스 카르테리 | |

| 도메인: | Eukaryota (Chatton, 1925) Whittaker & Margulis, 1978 |

| Plantae, Animalia 또는 Fungi 왕국으로 분류 할 수없는 진핵 생물은 때때로 paraphyly Protista에 그룹화됩니다. | |

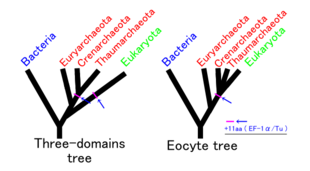

Eukaryotes (/juːˈkærioʊ t s, -əts/)는 세포가 핵 외피 내에 둘러싸인 핵을 가진 유기체입니다. [1][2][3] 그들은 유카리요타 또는 유카리아 유기체의 그룹에 속한다. 그들의 이름은 그리스어 εὖ (eu, "well"또는 "good")와 κάρυον (karyon, "nut"또는 "kernel")에서 유래했습니다. [4] Eukaryota 도메인은 삶의 세 가지 영역 중 하나를 구성합니다. 박테리아와 고세균 (둘 다 원핵생물)은 다른 두 도메인을 구성합니다. [5][6] 진핵생물은 대개 이제 고세균에서 출현했거나 아스가르드 고세균의 자매로 간주된다. [7][8] 이것은 박테리아와 고세균이라는 두 가지 생명 영역이 있으며, 진핵생물이 고세균 사이에 통합되어 있음을 의미합니다. [9][10] 진핵생물은 유기체 수의 소수를 나타낸다; [11] 그러나, 그들의 일반적으로 훨씬 더 큰 크기 때문에, 그들의 집단적 글로벌 바이오 매스는 원핵 생물의 그것과 거의 동등한 것으로 추정된다. [11] Eukaryotes는 대략 2.3-1.8 십억 년 전에, Proterozoic eon 동안, 편모 식영양 (flagellated phagotrophs)으로 나타났습니다. [12][13]

진핵 세포는 전형적으로 미토콘드리아 및 골지 장치와 같은 다른 막-결합된 소기관을 함유하고; 엽록체는 식물과 조류에서 발견 될 수 있습니다. 원핵 세포는 원시적 소기관을 함유할 수 있다. [14] 진핵생물은 단세포 또는 다세포일 수 있으며, 상이한 종류의 조직을 형성하는 많은 세포 유형을 포함한다; 비교해 보면, 원핵생물은 전형적으로 단세포성이다. 동물, 식물 및 곰팡이는 가장 친숙한 진핵 생물입니다. 다른 진핵 생물은 때때로 protists라고 불립니다. [15]

Eukaryotes는 유사분열을 통해 무성적으로 그리고 meiosis와 gamete 융합을 통해 성적으로 재현 할 수 있습니다. 유사분열에서는 한 세포가 분열하여 유전적으로 동일한 두 개의 세포를 생산합니다. meiosis에서, DNA 복제는 네 개의 반수체 딸 세포를 생산하기 위해 두 차례의 세포 분열을 거칩니다. 이들은 성 세포 또는 게이머 역할을합니다. 각 gamete는 단지 하나의 염색체 세트를 가지고 있으며, 각각은 meiosis 동안 유전 적 재조합으로 인한 부모 염색체의 해당 쌍의 고유 한 혼합입니다. [16]

셀 기능[편집]

진핵 세포는 전형적으로 원핵생물의 세포보다 훨씬 크며, 원핵 세포보다 약 10,000배 더 큰 부피를 갖는다. [17] 그들은 소기관이라고 불리는 다양한 내부 막 결합 구조와 미세 소관, 미세 필라멘트 및 중간 필라멘트로 구성된 세포 골격을 가지고 있으며, 이는 세포의 조직과 모양을 정의하는 데 중요한 역할을합니다. 진핵 DNA는 염색체라고 불리는 몇 가지 선형 다발로 나뉘며, 이는 핵 분열 중에 미세관형 스핀들에 의해 분리된다.

내부 멤브레인[편집]

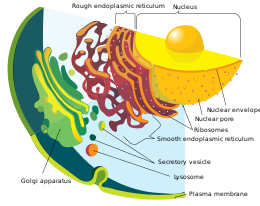

진핵생물 세포는 다양한 막-결합 구조를 포함하며, 집합적으로 내막 시스템으로 지칭된다. [18] 소포와 액포라고 불리는 단순한 구획은 다른 막에서 싹을 틔워서 형성 할 수 있습니다. 많은 세포가 endocytosis의 과정을 통해 음식과 다른 물질을 섭취하는데, 여기서 외막은 질내 인 다음 핀치되어 소포를 형성합니다. [19] 대부분의 다른 막 결합 소기관이 궁극적으로 그러한 소포로부터 유래 될 가능성이 있습니다 [인용 필요]. 대안적으로 세포에 의해 생산된 일부 생성물은 엑소사이토시스를 통해 소포에 남을 수 있다.

핵은 핵 외피로 알려진 이중 막으로 둘러싸여 있으며, 물질이 들어오고 나갈 수있는 핵 기공이 있습니다. [20] 핵막의 다양한 튜브 및 시트형 연장은 단백질 수송 및 성숙에 관여하는 소포체를 형성한다. 그것은 내부 공간이나 내강으로 들어가는 합성 단백질에 리보솜이 부착되는 거친 소포체를 포함합니다. 그 후, 그들은 일반적으로 부드러운 소포체에서 싹을 틔우는 소포에 들어갑니다. [21] 대부분의 진핵생물에서, 이들 단백질-운반 소포는 방출되고 골지 장치인 평탄한 소포(cisternae)의 스택에서 추가로 변형된다. [22]

소포는 다양한 목적으로 전문화 될 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 리소좀은 세포질의 대부분의 생체 분자를 분해하는 소화 효소를 함유하고 있습니다. [23] 퍼옥시솜은 과산화물을 분해하는데 사용되며, 이는 그렇지 않으면 독성이 있다. 많은 원생 동물은 과도한 물을 모으고 배출하는 수축성 액포와 포식자를 편향시키거나 먹이를 잡는 데 사용되는 물질을 배출하는 압출물을 가지고 있습니다. 고등 식물에서는 세포 부피의 대부분이 주로 물을 포함하고 주로 삼투압을 유지하는 중앙 액포에 의해 흡수됩니다.

미토콘드리아[편집]

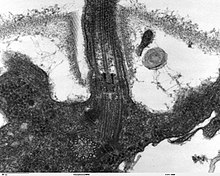

미토콘드리아는 진핵생물 1개를 제외한 모든 소기관이며,[주 1] 일반적으로 "세포의 강국"이라고 불린다. [25] 미토콘드리아는 설탕이나 지방을 산화시키고 ATP로 에너지를 방출함으로써 진핵 세포에 에너지를 제공한다. [26] 그들은 두 개의 주변 막을 가지고 있으며, 각각은 인지질 이중층이다. 그 내부는 호기성 호흡이 일어나는 cristae라고 불리는 질로 접혀 있습니다.

외부 미토콘드리아 막은 자유롭게 투과성이 있으며 거의 모든 것이 막간 공간으로 들어갈 수 있으며 내부 미토콘드리아 막은 반 투과성이므로 미토콘드리아 매트릭스에 필요한 것들 만 허용합니다.

미토콘드리아는 박테리아 DNA와 밀접한 구조적 유사성을 가지고 있으며, 진핵 단백질보다 박테리아 RNA에 구조적으로 더 가까운 RNA를 생산하는 rRNA 및 tRNA 유전자를 암호화하는 자체 DNA를 포함합니다. [27] 그들은 지금 일반적으로 내공생 원핵생물, 아마 알파프로테오박테리아로부터 발달한 것으로 유지된다.

Giardia 및 Trichomonas와 같은 메타모나드와 아메보조안 펠로믹사와 같은 일부 진핵생물은 미토콘드리아가 부족한 것으로 보이지만, 모두 수소수소솜 및 미토솜과 같은 미토콘드리온 유래 소기관을 포함하는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 따라서 미토콘드리아를 이차적으로 잃었습니다. [24] 그들은 환경에서 흡수 된 영양소에 대한 효소 작용으로 에너지를 얻습니다. 메타모나드 모노세르코모노나이드는 또한 측방 유전자 전달에 의해 단백질 합성에 필요한 철과 황의 클러스터를 제공하는 세포질 황 동원 시스템을 획득했다. 정상적인 미토콘드리아 철-황 클러스터 경로는 이차적으로 손실되었다. [24][28]

색소체[편집]

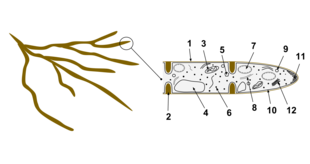

식물과 조류의 다양한 그룹도 색소체를 가지고 있습니다. 색소체는 또한 자신의 DNA를 가지고 있으며 endosymbionts,이 경우 시아 노 박테리아에서 개발됩니다. 그들은 보통 시아 노 박테리아와 마찬가지로 엽록소를 함유하고 광합성을 통해 유기 화합물 (예 : 포도당)을 생산하는 엽록체의 형태를 취합니다. 다른 사람들은 음식을 저장하는 데 관여합니다. 색소체는 아마도 단일 기원을 가졌지 만, 모든 색소체 함유 그룹이 밀접하게 관련되어있는 것은 아닙니다. 대신, 일부 진핵생물은 이차 내공생 또는 섭취를 통해 다른 사람들로부터 그들을 얻었습니다. [29] 광합성 세포와 엽록체의 포획 및 격리는 많은 유형의 현대 진핵 생물에서 발생하며 kleptoplasty로 알려져 있습니다.

내공생 기원은 또한 핵 및 진핵 편모에 대해 제안되었다. [30]

세포골격 구조[편집]

많은 진핵생물은 편모라고 불리는 긴 가느다란 운동성 세포질 돌출부 또는 섬모라고 불리는 유사한 구조를 가지고 있습니다. 편모와 섬모는 때때로 undulipodia로 불리며,[31] 운동, 수유 및 감각에 다양하게 관여합니다. 그들은 주로 튜불린으로 구성됩니다. 이들은 원핵 편모와 완전히 구별됩니다. 그들은 두 개의 싱글릿을 둘러싼 아홉 개의 이중으로 특징적으로 배열 된 중심에서 발생하는 미세 소관 묶음에 의해지지됩니다. 편모는 또한 머리카락, 또는 mastigonemes, 그리고 막과 내부 막대를 연결하는 비늘을 가질 수 있습니다. 그들의 내부는 세포의 세포질과 연속적입니다.

액틴 및 액틴 결합 단백질, 예를 들어, α-액티닌, 핌브린, 필라민으로 구성된 미세 필라멘탈 구조는 또한 막하 피질층 및 다발에 존재한다. 미세소관의 운동 단백질, 예를 들어, 다인 또는 키네신 및 액틴, 예를 들어, 미오신은 네트워크의 동적 특성을 제공한다.

Centrioles는 편모가없는 세포와 그룹에도 종종 존재하지만 침엽수와 꽃 피는 식물은 둘 다 가지고 있지 않습니다. 그들은 일반적으로 다양한 미세 관형 뿌리를 일으키는 그룹에서 발생합니다. 이들은 세포 골격 구조의 주요 구성 요소를 형성하며, 종종 여러 세포 분열의 과정에 걸쳐 조립되며, 하나의 편모는 부모로부터 유지되고 다른 편모는 그것으로부터 유래됩니다. Centrioles는 핵 분열 중에 스핀들을 생산합니다. [32]

세포 골격 구조의 중요성은 세포의 모양 결정뿐만 아니라 화학 요법 및 화학 요법과 같은 철새 반응의 필수 구성 요소라는 점에서 강조됩니다. 일부 원생 동물은 다양한 다른 미세 소관 지원 소기관을 가지고 있습니다. 여기에는 부양에 사용되거나 먹이를 잡기 위해 사용되는 axopodia를 생산하는 radiolaria 및 heliozoa와 haptonema라고 불리는 독특한 편모와 같은 소기관을 가진 haptophytes가 포함됩니다.

세포벽[편집]

식물과 조류, 곰팡이 및 대부분의 염색체 세포의 세포는 세포벽, 세포막 외부의 층을 가지고있어 세포에 구조적 지원, 보호 및 필터링 메커니즘을 제공합니다. 세포벽은 또한 물이 세포에 들어갈 때 과도한 팽창을 방지합니다. [33]

육상 식물의 주요 세포벽을 구성하는 주요 다당류는 셀룰로오스, 헤미셀룰로오스 및 펙틴입니다. 셀룰로스 마이크로피브릴은 헤미셀룰로오스 테더를 통해 연결되어 펙틴 매트릭스에 매립되는 셀룰로스-헤미셀룰로오스 네트워크를 형성한다. 일차 세포벽에서 가장 흔한 헤미셀룰로오스는 자일로글루칸이다. [34]

진핵 세포의 차이[편집]

동물과 식물이 가장 친숙한 진핵 생물이지만 진핵 세포에는 여러 가지 유형이 있으므로 진핵 구조를 이해하기위한 훌륭한 출발점을 제공합니다. 그러나 곰팡이와 많은 protists는 몇 가지 실질적인 차이가 있습니다.

동물 세포[편집]

모든 동물은 진핵생물이다. 동물 세포는 세포벽과 엽록체가 부족하고 액포가 작기 때문에 다른 진핵 생물, 특히 식물의 세포와 구별됩니다. 세포벽이 없기 때문에 동물 세포는 다양한 모양으로 변형 될 수 있습니다. 식세포 세포는 심지어 다른 구조를 삼킬 수 있습니다.

식물 세포[편집]

식물 세포는 다른 진핵 생물의 세포와 상당히 다르다. 그들의 독특한 특징은 다음과 같습니다.

- 큰 중앙 액포 (막, 토노플라스트로 둘러싸여있는)는 세포의 터거를 유지하고 시토졸과 수액 사이의 분자 이동을 제어합니다.[35]

- 세포막의 외부에 원형질체에 의해 증착된 셀룰로스, 헤미셀룰로오스 및 펙틴을 함유하는 일차 세포벽; 이것은 키틴을 함유 한 곰팡이의 세포벽과 펩티도글리칸이 주요 구조 분자 인 원핵 생물의 세포 외피와 대조됩니다.

- 플라스모데스마타(plasmodesmata)는 인접한 세포를 연결하고 식물 세포가 인접한 세포와 소통할 수 있도록 하는 세포벽의 기공이다. [36] 동물은 인접한 세포들 사이의 갭 접합의 다르지만 기능적으로 유사한 시스템을 가지고 있다.

- 색소체, 특히 엽록체, 엽록소를 함유 한 소기관, 식물에 녹색을 부여하고 광합성을 수행 할 수있는 안료

- Bryophytes와 씨앗이없는 혈관 식물은 정자 세포에 편모와 중심 만 가지고 있습니다. [37] cycads와 은행나무의 정자는 수십에서 수천 개의 편모로 수영하는 크고 복잡한 세포입니다. [38]

- 침엽수 (Pinophyta)와 꽃 피는 식물 (Angiospermae)은 동물 세포에 존재하는 편모와 중심이 부족합니다.

곰팡이 세포[편집]

곰팡이의 세포는 동물 세포와 유사하지만 다음과 같은 예외가 있습니다 :[39]

- 키틴을 포함하는 세포벽

- 세포 사이의 더 적은 구획; 더 높은 곰팡이의 균사는 세포질, 소기관, 때로는 핵의 통과를 허용하는 septa라고 불리는 다공성 파티션을 가지고 있습니다. 그래서 각 유기체는 본질적으로 거대한 다핵 수퍼 세포입니다.이 곰팡이는 coenocytic으로 묘사됩니다. 원시 균류에는 셉타가 거의 없거나 전혀 없습니다.

- 가장 원시적 인 곰팡이 인 키트리드 (chytrids) 만이 편모를 가지고 있습니다.

다른 진핵 세포[편집]

진핵생물의 일부 그룹에는 녹내장의 시아넬(특이한 색소체), [40] 합토피테의 합톤마, 또는 크립토모나드의 이젝토솜과 같은 독특한 소기관이 있다. 슈도포디아와 같은 다른 구조는 다양한 형태의 다양한 진핵생물 그룹에서 발견되며, 예를 들어 로보스 아메보조아 또는 레티쿨로스 포라미니페란과 같은 형태가 있다. [41]

Reproduction[edit]

Cell division generally takes place asexually by mitosis, a process that allows each daughter nucleus to receive one copy of each chromosome. Most eukaryotes also have a life cycle that involves sexual reproduction, alternating between a haploid phase, where only one copy of each chromosome is present in each cell and a diploid phase, wherein two copies of each chromosome are present in each cell. The diploid phase is formed by fusion of two haploid gametes to form a zygote, which may divide by mitosis or undergo chromosome reduction by meiosis. There is considerable variation in this pattern. Animals have no multicellular haploid phase, but each plant generation can consist of haploid and diploid multicellular phases.

Eukaryotes have a smaller surface area to volume ratio than prokaryotes, and thus have lower metabolic rates and longer generation times.[42]

The evolution of sexual reproduction may be a primordial and fundamental characteristic of eukaryotes. Based on a phylogenetic analysis, Dacks and Roger proposed that facultative sex was present in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes.[43] A core set of genes that function in meiosis is present in both Trichomonas vaginalis and Giardia intestinalis, two organisms previously thought to be asexual.[44][45] Since these two species are descendants of lineages that diverged early from the eukaryotic evolutionary tree, it was inferred that core meiotic genes, and hence sex, were likely present in a common ancestor of all eukaryotes.[44][45] Eukaryotic species once thought to be asexual, such as parasitic protozoa of the genus Leishmania, have been shown to have a sexual cycle.[46] Also, evidence now indicates that amoebae, previously regarded as asexual, are anciently sexual and that the majority of present-day asexual groups likely arose recently and independently.[47]

Classification[edit]

In antiquity, the two lineages of animals and plants were recognized. They were given the taxonomic rank of Kingdom by Linnaeus. Though he included the fungi with plants with some reservations, it was later realized that they are quite distinct and warrant a separate kingdom, the composition of which was not entirely clear until the 1980s.[48] The various single-cell eukaryotes were originally placed with plants or animals when they became known. In 1818, the German biologist Georg A. Goldfuss coined the word protozoa to refer to organisms such as ciliates,[49] and this group was expanded until it encompassed all single-celled eukaryotes, and given their own kingdom, the Protista, by Ernst Haeckel in 1866.[50][51] The eukaryotes thus came to be composed of four kingdoms:

The protists were understood to be "primitive forms", and thus an evolutionary grade, united by their primitive unicellular nature.[51] The disentanglement of the deep splits in the tree of life only really started with DNA sequencing, leading to a system of domains rather than kingdoms as top level rank being put forward by Carl Woese, uniting all the eukaryote kingdoms under the eukaryote domain.[52] At the same time, work on the protist tree intensified, and is still actively going on today. Several alternative classifications have been forwarded, though there is no consensus in the field.

Eukaryotes are a clade usually assessed to be sister to Heimdallarchaeota in the Asgard grouping in the Archaea.[53][54][55] In one proposed system[which?], the basal groupings are the Opimoda, Diphoda, the Discoba, and the Loukozoa. The Eukaryote root is usually assessed to be near or even in Discoba[citation needed].

A classification produced in 2005 for the International Society of Protistologists,[56] which reflected the consensus of the time, divided the eukaryotes into six supposedly monophyletic 'supergroups'. However, in the same year (2005), doubts were expressed as to whether some of these supergroups were monophyletic, particularly the Chromalveolata,[57] and a review in 2006 noted the lack of evidence for several of the supposed six supergroups.[58] A revised classification in 2012[59] recognizes five supergroups.

| Archaeplastida (or Primoplantae) |

Land plants, green algae, red algae, and glaucophytes |

| SAR supergroup | Stramenopiles (brown algae, diatoms, etc.), Alveolata, and Rhizaria (Foraminifera, Radiolaria, and various other amoeboid protozoa) |

| Excavata | Various flagellate protozoa |

| Amoebozoa | Most lobose amoeboids and slime molds |

| Opisthokonta | Animals, fungi, choanoflagellates, etc. |

There are also smaller groups of eukaryotes whose position is uncertain or seems to fall outside the major groups[60] – in particular, Haptophyta, Cryptophyta, Centrohelida, Telonemia, Picozoa,[61] Apusomonadida, Ancyromonadida, Breviatea, and the genus Collodictyon.[62] Overall, it seems that, although progress has been made, there are still very significant uncertainties in the evolutionary history and classification of eukaryotes. As Roger & Simpson said in 2009 "with the current pace of change in our understanding of the eukaryote tree of life, we should proceed with caution."[63] Newly identified protists, purported to represent novel, deep-branching lineages, continue to be described well into the 21st century; recent examples including Rhodelphis, putative sister group to Rhodophyta, and Anaeramoeba, anaerobic amoebaflagellates of uncertain placement.[64]

Phylogeny[edit]

The rRNA trees constructed during the 1980s and 1990s left most eukaryotes in an unresolved "crown" group (not technically a true crown), which was usually divided by the form of the mitochondrial cristae; see crown eukaryotes. The few groups that lack mitochondria branched separately, and so the absence was believed to be primitive; but this is now considered an artifact of long-branch attraction, and they are known to have lost them secondarily.[65][66]

It has been estimated that there may be 75 distinct lineages of eukaryotes.[67] Most of these lineages are protists.

The known eukaryote genome sizes vary from 8.2 megabases (Mb) in Babesia bovis to 112,000–220,050 Mb in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum micans, showing that the genome of the ancestral eukaryote has undergone considerable variation during its evolution.[67] The last common ancestor of all eukaryotes is believed to have been a phagotrophic protist with a nucleus, at least one centriole and cilium, facultatively aerobic mitochondria, sex (meiosis and syngamy), a dormant cyst with a cell wall of chitin and/or cellulose and peroxisomes.[67] Later endosymbiosis led to the spread of plastids in some lineages.

Although there is still considerable uncertainty in global eukaryote phylogeny, particularly regarding the position of the root, a rough consensus has started to emerge from the phylogenomic studies of the past two decades.[60][68][69][70][71][72][24][73][64] The majority of eukaryotes can be placed in one of two large clades dubbed Amorphea (similar in composition to the unikont hypothesis) and the Diaphoretickes, which includes plants and most algal lineages. A third major grouping, the Excavata, has been abandoned as a formal group in the most recent classification of the International Society of Protistologists due to growing uncertainty as to whether its constituent groups belong together.[74] The proposed phylogeny below includes only one group of excavates (Discoba), and incorporates the recent proposal that picozoans are close relatives of rhodophytes.[75]

| Eukaryotes | |

In some analyses, the Hacrobia group (Haptophyta + Cryptophyta) is placed next to Archaeplastida,[76] but in others it is nested inside the Archaeplastida.[77] However, several recent studies have concluded that Haptophyta and Cryptophyta do not form a monophyletic group.[78] The former could be a sister group to the SAR group, the latter cluster with the Archaeplastida (plants in the broad sense).[79]

The division of the eukaryotes into two primary clades, bikonts (Archaeplastida + SAR + Excavata) and unikonts (Amoebozoa + Opisthokonta), derived from an ancestral biflagellar organism and an ancestral uniflagellar organism, respectively, had been suggested earlier.[77][80][81] A 2012 study produced a somewhat similar division, although noting that the terms "unikonts" and "bikonts" were not used in the original sense.[61]

A highly converged and congruent set of trees appears in Derelle et al. (2015), Ren et al. (2016), Yang et al. (2017) and Cavalier-Smith (2015) including the supplementary information, resulting in a more conservative and consolidated tree. It is combined with some results from Cavalier-Smith for the basal Opimoda.[82][83][84][85][86][71][87] The main remaining controversies are the root, and the exact positioning of the Rhodophyta and the bikonts Rhizaria, Haptista, Cryptista, Picozoa and Telonemia, many of which may be endosymbiotic eukaryote-eukaryote hybrids.[88] Archaeplastida acquired chloroplasts probably by endosymbiosis of a prokaryotic ancestor related to a currently extant cyanobacterium, Gloeomargarita lithophora.[89][90][88]

| Eukaryotes | |

Cavalier-Smith's tree[edit]

Thomas Cavalier-Smith 2010,[91] 2013,[92] 2014,[93] 2017[83] and 2018[94] places the eukaryotic tree's root between Excavata (with ventral feeding groove supported by a microtubular root) and the grooveless Euglenozoa, and monophyletic Chromista, correlated to a single endosymbiotic event of capturing a red-algae. He et al.[95] specifically supports rooting the eukaryotic tree between a monophyletic Discoba (Discicristata + Jakobida) and an Amorphea-Diaphoretickes clade.

| Eukaryotes | |

진화의 역사[편집]

진핵생물의 기원 [편집]

진핵 세포의 기원은 진핵 생물이 모든 복잡한 세포와 거의 모든 다세포 유기체를 포함하기 때문에 생명의 진화의 이정표입니다. 첫 번째 진핵 생물과 가장 가까운 친척을 찾기 위해 여러 가지 접근법이 사용되었습니다. 마지막 진핵 공통 조상 (LECA)은 모든 살아있는 진핵 생물의 가설적인 마지막 공통 조상이며,[5] 생물학적 집단이었을 가능성이 가장 큽니다. [99]

진핵생물은 내막 시스템과 스테란 합성과 같은 독특한 생화학적 경로를 포함한 원핵생물과 구별되는 많은 특징을 가지고 있다. [100] 진핵 시그니처 단백질 (ESPs)이라고 불리는 일련의 단백질이 2002 년에 진핵 친척을 확인하기 위해 제안되었다 : 그들은 그때까지 다른 삶의 영역에서 알려진 단백질과 상동성이 없지만 진핵 생물들 사이에서 보편적 인 것으로 보인다. 여기에는 세포 골격을 구성하는 단백질, 복잡한 전사 기계, 막 분류 시스템, 핵 기공 및 생화학 적 경로의 일부 효소가 포함됩니다. [101]

화석[편집]

이 일련의 사건의 타이밍은 결정하기가 어렵습니다. Knoll (2006)은 약 1.6-2.1 억 년 전에 개발되었다고 제안합니다. 일부 acritarchs는 적어도 1.65 억 년 전부터 알려져 있으며, 가능한 alga Grypania는 2.1 억 년 전으로 거슬러 올라갑니다. [102] Geosiphon과 같은 화석 균류 Diskagma는 2.2 억 년 된 paleosols에서 발견되었습니다. [103]

조직 된 살아있는 구조는 2.1 억 년 된 가봉의 Palaeoproterozoic Francevillian B Formation의 검은 셰일에서 발견되었습니다. 진핵 생물은 그 당시 진화 할 수있었습니다. [104] 현대 집단과 명백하게 관련된 화석들은 약 1.2 억 년 전에, 홍조류의 형태로 나타나기 시작하지만, 최근의 연구는 아마도 1.6 ~ 1.7 억 년 전으로 거슬러 올라가는 빈디야 유역에 화석화 된 필라멘트 조류의 존재를 시사한다. [105]

호주 셰일에서 진핵 특이적 바이오마커(스테란)의 존재는 이전에 진핵생물이 2.7억 년 된 이 암석에 존재한다는 것을 나타냈으며,[100][106] 이는 대산화 사건 동안 상당한 양의 분자 산소에 대한 최초의 지질학적 기록보다 훨씬 3억 년 더 오래되었다. . 그러나, 이들 Archaean 바이오마커는 결국 후대의 오염물질로서 반박되었다. [107] 현재, 추정적으로 가장 오래된 바이오마커 기록은 단지 ~8억 년 전이다. [108] 대조적으로, 분자 시계 분석은 2.3 억 년 전에 스테롤 생합성의 출현을 암시하며,[109] 따라서 분자 데이터와 지질 데이터 사이에는 엄청난 차이가 있으며, 이는 8 억 년 전에 바이오 마커 기록을 통한 진핵 진화의 합리적인 추론을 방해한다. 진핵 바이오마커로서의 스테란의 성질은 일부 박테리아에 의한 스테롤의 생산에 의해 더욱 복잡해진다. [110][111]

그들의 기원이 될 때마다, 진핵 생물은 훨씬 나중에까지 생태 학적으로 지배적이되지 않았을 수도 있습니다. 8억 년 전 해양 퇴적물의 아연 조성이 크게 증가한 것은 진핵생물의 상당한 개체군이 증가한 데 기인하며, 진핵생물은 원산지 이후 약 십억 년 후(늦어도 원핵생물에 비해 아연을 우선적으로 섭취하고 통합한다). [112]

2019년 4월, 생물학자들은 매우 큰 메두사바이러스, 또는 친척이 적어도 부분적으로는 단순한 원핵 세포로부터 복잡한 진핵 세포의 진화적 출현에 책임이 있었을 것이라고 보고했다. [113]

고고학과의 관계[편집]

진핵생물의 핵 DNA와 유전 기계는 박테리아보다 Archaea와 더 유사하며, 진핵생물이 클래드 네오무라의 Archaea와 함께 그룹화되어야한다는 논란의 여지가있는 제안으로 이어진다. 막 조성과 같은 다른 측면에서, 진핵생물은 박테리아와 유사하다. 이에 대한 세 가지 주요 설명이 제안되었습니다.

- 진핵생물은 둘 이상의 세포의 완전한 융합으로부터 유래되었으며, 여기서 세포질은 박테리아로부터 형성되고, 고세균으로부터의 핵,[114] 바이러스로부터,[115][116] 또는 전세포로부터 형성되었다. [117][118]

- Eukaryotes는 Archaea에서 개발되었으며, 박테리아 기원의 원형 미토콘드리온의 내공생을 통해 박테리아 특성을 획득했습니다. [119]

- Eukaryotes와 Archaea는 변형 된 박테리아와 별도로 개발되었습니다.

대체 제안은 다음과 같습니다.

- 크로노사이트 가설은 원시적 진핵 세포가 크로노사이트(chronocyte)라고 불리는 세 번째 유형의 세포에 의해 고세균과 박테리아 모두의 내공생에 의해 형성되었다고 가정한다. 이것은 주로 진핵 서명 단백질이 2002 년까지 다른 곳에서는 발견되지 않았다는 사실을 설명하기위한 것입니다. [101]

- 현재의 생명 나무의 보편적 인 공통 조상 (UCA)은 생명의 진화의 초기 단계보다는 대량 멸종 사건에서 살아남은 복잡한 유기체였습니다. Eukaryotes 및 특히 akaryotes (박테리아와 Archaea)는 환원적 손실을 통해 진화하여 유사성이 원래 특징의 차등 보존에서 비롯됩니다. [121]

다른 그룹이 관여하지 않는다고 가정하면, 박테리아, 고고학 및 진핵종에 대한 세 가지 가능한 계통학이 있으며, 각각은 단일 계통입니다. 아래 표에서 1 ~ 3으로 표시되어 있습니다. eocyte 가설은 Archaea가 paraphyletic이라는 가설 2의 수정입니다. (가설의 표와 이름은 Harish and Kurland, 2017을 기반으로합니다. [122])

생명나무의 기초에 대한 대안적 가설1 - 두 제국2 – 세 도메인3 - 굽타4 – 난모세포최근 몇 년 동안 대부분의 연구자들은 3 도메인 (3D) 또는 eocyte 가설을 선호했습니다. rRNA 분석은 Excavata의 진핵 뿌리가있는 것으로 보이는 eocyte 시나리오를 지원합니다. [98][91][92][93][83] 아스가르드 고세균의 계통 분석에 기초한 고고학 내에 진핵생물을 위치시키는 난모세포 가설을 지지하는 클라도그램은 다음과 같다:[53][54][55][10]

| "프로테오아카에오타" | |

이 시나리오에서, 아스가르드 그룹은 Thermoproteota (이전의 eocytes 또는 Crenarchaeota로 명명 됨), Nitrososphaerota (이전의 Thaumarchaeota) 및 기타로 구성된 TACK 그룹의 자매 분류로 간주됩니다. 이 그룹은 많은 진핵 시그니처 단백질을 함유하고 소포를 생산하는 것으로 보고되었다. [123]

2017 년에이 시나리오에 대한 상당한 반발이 있었고, 진핵 생물이 고고학 내에서 나타나지 않았다고 주장했다. Cunha et al.은 3 개의 도메인 (3D) 또는 Woese 가설 (위의 표의 2)을 지원하고 eocyte 가설 (위의 4)을 거부하는 분석을 생성했습니다. [124] Harish와 Kurland는 단백질 도메인의 코딩 서열 분석에 근거하여 초기 두 제국 (2D) 또는 Mayr 가설 (위의 표의 1)에 대한 강력한지지를 발견했습니다. 그들은 난모세포 가설을 가장 가능성이 낮은 것으로 거부했다. [125][122] 그들의 분석에 대한 가능한 해석은 현재의 생명 나무의 보편적 공통 조상 (UCA)이 생명의 역사 초기에 발생하는 단순한 유기체라기보다는 진화론 적 병목 현상에서 살아남은 복잡한 유기체라는 것입니다. [121] 한편, 아스가르드를 생각해 낸 연구자들은 추가 아스가르드 샘플을 통해 그들의 가설을 재확인했다. [126] 그 이후로, 추가적인 아스가르드 고고 게놈의 출판과 다수의 독립적인 실험실에 의한 계통 유전체 나무의 독립적 인 재구성은 진핵 생물의 아스가르드 고고 기원에 대한 추가적인 지원을 제공했다.

Asgard archaea 구성원과 진핵 생물의 관계에 대한 세부 사항은 여전히 고려 중이지만,[127] 2020 년 1 월에 과학자들은 배양 된 Asgard archaea의 일종 인 Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum이 약 20 억 년 전에 단순한 원핵 생물과 복잡한 진핵 미생물 사이의 가능한 연결 고리 일 수 있다고보고했다. [128][123]

내막 시스템과 미토콘드리아[편집]

내막 시스템과 미토콘드리아의 기원도 불분명하다. [129] 식영양 가설은 세포벽이 결여된 진핵생물형 막이 엔도사이토시스의 발달과 함께 먼저 유래한 반면, 미토콘드리아는 내공생물질로서 섭취함으로써 획득되었다고 제안한다. [130] syntrophic 가설은 원시-진핵생물이 원시-미토콘드리온에 의존하여 음식을 먹었고, 그래서 궁극적으로 그것을 둘러싸기 위해 성장했다고 제안한다. 여기서 막은 미토콘드리온의 삼킴 이후에 유래했는데, 부분적으로는 미토콘드리아 유전자 덕분입니다 (수소 가설은 하나의 특정 버전입니다). [131]

수퍼 트리를 만들기 위해 게놈을 사용하는 연구에서 Pisani et al. (2007)는 미토콘드리온이없는 진핵생물이 결코 존재하지 않았다는 증거와 함께 진핵 생물은 Thermoplasmatales와 밀접한 관련이있는 고세균과 알파 프로테오박테리움 사이의 신트로피에서 진화했으며, 이는 황이나 수소에 의해 구동되는 공생 일 가능성이 높다고 제안합니다. 미토콘드리온과 그 게놈은 알파프로테오박테리아 내공생물질의 잔재이다. [132] 공생자로부터의 유전자의 대부분은 핵으로 옮겨졌다. 그들은 진핵 세포의 대사 및 에너지 관련 경로의 대부분을 구성하는 반면, 정보 시스템 (DNA 중합 효소, 전사, 번역)은 고세균에서 유지됩니다. [133]

가설[편집]

진핵 세포가 어떻게 존재하게되었는지에 대한 다른 가설이 제안되었습니다. 이러한 가설은 두 가지 별개의 클래스, 즉 자생 모델과 키메라 모델로 분류 될 수 있습니다.

자동 모델[편집]

자가-생성 모델은 핵을 포함하는 원시-진핵 세포가 먼저 존재했고, 나중에는 미토콘드리아를 획득했다고 제안한다. [134] 이 모델에 따르면, 큰 원핵생물은 세포질 부피를 제공하기에 충분한 표면적을 얻기 위해 원형질막에 질내 염증을 일으켰다. 질내 기능이 분화됨에 따라 일부는 별도의 구획이되어 소포체, 골지 장치, 핵막 및 리소좀과 같은 단일 막 구조를 포함한 내막 시스템을 야기했습니다. [135]

미토콘드리아는 호기성 프로테오박테리움의 내공생에서 비롯된 것으로 제안되며, 미토콘드리아를 획득하지 못한 모든 진핵 혈통이 멸종된 것으로 추정된다. [136] 엽록체는 시아노박테리아와 관련된 또 다른 내공생 사건에서 비롯되었다. 모든 알려진 진핵생물은 미토콘드리아를 가지고 있지만, 모두가 엽록체를 가지고 있는 것은 아니기 때문에, 직렬 내공생 이론은 미토콘드리아가 먼저 왔다고 제안한다.

키메라 모델[편집]키메라 모델은 두 개의 원핵 세포가 처음에 존재했다고 주장합니다 - 고세균과 박테리아. 이들 중 가장 가까운 살아있는 친척은 Asgardarchaeota와 (멀리 관련된) proto-mitochondrion이라고 불리는 알파 프로테오 박테리아 인 것으로 보입니다. [137][138] 이들 세포는 물리적 융합 또는 내공생에 의해 병합 과정을 거쳤고, 이로써 진핵 세포의 형성을 유도하였다. 이러한 키메라 모델 내에서 일부 연구는 미토콘드리아가 박테리아 조상에서 유래했다고 주장하는 반면, 다른 연구는 미토콘드리아의 기원 뒤에있는 내공생 과정의 역할을 강조합니다.

내부 가설[편집]내부 가설은 자유 살아있는 미토콘드리아와 같은 박테리아와 진핵 세포로의 고세균 사이의 융합이 단일 식세포 사건이 아닌 장기간에 걸쳐 점차적으로 발생했음을 시사합니다. 이 시나리오에서, 고세균은 호기성 박테리아를 세포 돌출부로 포획 한 다음 소화하는 대신 에너지를 끌어 내기 위해 그들을 살아 있게 할 것입니다. 초기 단계에서 박테리아는 여전히 부분적으로 환경과 직접 접촉 할 것이고, 고세균은 필요한 모든 영양소를 제공 할 필요가 없었습니다. 그러나 결국 고세균은 박테리아를 완전히 삼켜 내부 막 구조와 핵막을 만들었습니다. [139]

할로필레스(halophiles)라고 불리는 고세균 집단은 미생물 세계에서 흔히 발생하는 기존의 수평적 유전자 전달을 통하는 것보다 훨씬 더 많은 박테리아로부터 천 개의 유전자를 획득한 유사한 과정을 거쳤다고 가정하지만, 두 미생물은 하나의 진핵생물과 같은 세포로 융합되기 전에 다시 분리되었다. [140]

내부 가설의 확장 된 버전은 진핵 세포가 두 원핵 생물 사이의 물리적 상호 작용에 의해 만들어졌으며 진핵 생물의 마지막 공통 조상이 협동 관계에 참여하는 미생물의 전체 집단 또는 공동체로부터 게놈을 얻어 환경에서 번성하고 생존 할 수 있다고 제안합니다. 다양한 종류의 미생물로부터의 게놈은 서로를 보완 할 것이고, 때때로 그들 사이의 수평 유전자 전달은 주로 그들 자신의 이익에 달려 있습니다. 유익한 유전자의 이러한 축적은 독립에 필요한 모든 유전자를 포함하는 진핵 세포의 게놈을 발생시켰다. [141][142][143]

직렬 내공생 가설[편집]직렬 내공생 이론 (Lynn Margulis가 옹호 한)에 따르면, 운동성 혐기성 박테리아 (Spirochaeta와 같은)와 열산성 성 크레나 쿤 (자연에서 황화 성 인 Thermoplasma와 같은) 사이의 연합은 오늘날의 진핵생물을 낳았습니다. 이 연합은 이미 존재하는 산성 및 유황 수역에서 살 수있는 운동성 유기체를 설립했습니다. 산소는 필요한 대사 기계가 부족한 유기체에 독성을 유발하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다. 따라서, 고세균은 박테리아에게 매우 유익한 환원 환경을 제공했다 (황 및 황산염은 황화물로 환원되었다). 미세 호기성 조건에서, 산소는 물로 환원되어 상호 이익 플랫폼을 생성하였다. 반면에 박테리아는 고세균에 운동성 특징과 함께 필요한 발효 생성물 및 전자 수용체를 기여하여 유기체에 대한 수영 운동성을 얻었습니다.

박테리아와 고고 DNA의 컨소시엄에서 진핵 세포의 핵 게놈을 기원했다. 스피로체테스는 진핵 세포의 운동성 특징을 발생시켰다. 알파프로테오박테리아와 시아노박테리아의 조상들의 내공생적 통일은 각각 미토콘드리아와 색소체의 기원으로 이어졌다. 예를 들어, Thiodendron은 Desulfobacter와 Spirochaeta라는 두 가지 유형의 박테리아 사이에 존재하는 유사한 유황 합성 트로피를 기반으로 한 외부 공생 과정을 통해 시작된 것으로 알려져 있습니다.

그러나 운동성 공생에 기초한 그러한 연관성은 실제로 관찰 된 적이 없습니다. 또한 고세균과 스피로 체트가 강렬한 산성 기반 환경에 적응한다는 증거는 없습니다. [134]

수소 가설[편집]수소 가설에서, 혐기성 및 독립영양 메타노겐 고세균(숙주)과 알파프로테오박테리움(공생자)의 공생적 결합은 진핵생물을 발생시켰다. 숙주는 수소(H2)와 이산화탄소(CO2)를 활용하여 메탄을 생산하면서 호기성 호흡이 가능한 공생물질은 혐기성 발효 공정의 부산물로 H2와CO2를 배출했다. 숙주의 메타노제닉 환경은H2의 싱크대 역할을 하여 박테리아 발효를 증가시켰다.

내공생 유전자 전달은 숙주가 공생자의 탄수화물 대사를 획득하고 자연에서 종속 영양을 전환시키는 촉매제 역할을했습니다. 그 후, 숙주의 메탄 형성 능력이 상실되었다. 따라서, 종속영양 소기관(symbiont)의 기원은 진핵 계통의 기원과 동일하다. 이 가설에서,H2의 존재는 원핵생물로부터 진핵생물을 위조하는 선택력을 나타낸다. [131]

신트로피 가설[편집]syntrophy 가설은 수소 가설과 대조적으로 개발되었으며 두 가지 공생 사건의 존재를 제안합니다. 이 모델에 따르면, 진핵 세포의 기원은 메타노겐 고세균과 델타프로테오박테리움 사이의 대사 공생(syntrophy)에 기초하였다. 이 syntrophic 공생은 처음에는 혐기성 환경 하에서 다른 종 간의H2 전달에 의해 촉진되었습니다. 초기 단계에서는 알파프로테오박테리움이 이러한 통합의 구성원이 되었고, 나중에는 미토콘드리온으로 발전했다. 델타프로테오박테리움에서 고세균으로의 유전자 전달은 메타노겐 고세균이 핵으로 발전하도록 이끌었다. 고세균은 유전 장치를 구성했고, 델타 프로테오박테리움은 세포질 특징에 기여했다.

This theory incorporates two selective forces at the time of nucleus evolution

- presence of metabolic partitioning to avoid the harmful effects of the co-existence of anabolic and catabolic cellular pathways, and

- prevention of abnormal protein biosynthesis due to a vast spread of introns in the archaeal genes after acquiring the mitochondrion and losing methanogenesis.[citation needed]

A complex scenario of 6+ serial endosymbiotic events of archaea and bacteria has been proposed in which mitochondria and an asgard related archaeota were acquired at a late stage of eukaryogenesis, possibly in combination, as a secondary endosymbiont.[144][145] The findings have been rebuked as an artifact.[146]

See also[edit]

- Eukaryote hybrid genome

- Evolution of sexual reproduction

- List of sequenced eukaryotic genomes

- Parakaryon myojinensis

- Prokaryote

- Nitrososphaerota

- Vault (organelle)

Notes[edit]

- ^ To date, only one eukaryote, Monocercomonoides, is known to have completely lost its mitochondria.[24]

References[edit]

- ^ Youngson RM (2006). Collins Dictionary of Human Biology. Glasgow: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-722134-9.

- ^ Nelson DL, Cox MM (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4339-2.

- ^ Martin EA, ed. (1983). Macmillan Dictionary of Life Sciences (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-0-333-34867-3.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "eukaryotic". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gabaldón, T (8 October 2021). "Origin and Early Evolution of the Eukaryotic Cell". Annual Review of Microbiology. 75 (1): 631–647. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062213. ISSN 0066-4227. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (June 1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ Zimmer C (11 April 2016). "Scientists Unveil New 'Tree of Life'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ Gribaldo S, Brochier-Armanet C (January 2020). "Evolutionary relationships between archaea and eukaryotes". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (1): 20–21. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-1073-1. PMID 31836857.

- ^ Doolittle WF (February 2020). "Evolution: Two Domains of Life or Three?". Current Biology. 30 (4): R177–R179. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.010. PMID 32097647.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Williams TA, Cox CJ, Foster PG, Szöllősi GJ, Embley TM (January 2020). "Phylogenomics provides robust support for a two-domains tree of life". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (1): 138–147. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-1040-x. PMC 6942926. PMID 31819234.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Whitman WB, Coleman DC, Wiebe WJ (June 1998). "Prokaryotes: the unseen majority" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (12): 6578–6583. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.6578W. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. PMC 33863. PMID 9618454. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ Leander BS (May 2020). "Predatory protists". Current Biology. 30 (10): R510–R516. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.052. PMID 32428491. S2CID 218710816.

- ^ Strassert, Jürgen F. H.; Irisarri, Iker; Williams, Tom A.; Burki, Fabien (2021). "A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids". Nature. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. PMC 7994803.

- ^ Murat D, Byrne M, Komeili A (October 2010). "Cell biology of prokaryotic organelles". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (10): a000422. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000422. PMC 2944366. PMID 20739411.

- ^ Whittaker RH (January 1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science. 163 (3863): 150–60. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.5430. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760.

- ^ Campbell NA, Cain ML, Minorsky PV, Reece JB, Urry LA (2018). "Chapter 13: Sexual Life Cycles and Meiosis". Biology: A Global Approach (11th ed.). New York: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-1-292-17043-5.

- ^ Yamaguchi M, Worman CO (2014). "Deep-sea microorganisms and the origin of the eukaryotic cell" (PDF). Jpn. J. Protozool. 47 (1, 2): 29–48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ Linka M, Weber AP (2011). "Evolutionary Integration of Chloroplast Metabolism with the Metabolic Networks of the Cells". In Burnap RL, Vermaas WF (eds.). Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems. Springer. p. 215. ISBN 978-94-007-1533-2. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Marsh M (2001). Endocytosis. Oxford University Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-963851-2.

- ^ Hetzer MW (March 2010). "The nuclear envelope". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (3): a000539. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000539. PMC 2829960. PMID 20300205.

- ^ "Endoplasmic Reticulum (Rough and Smooth)". British Society for Cell Biology. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Golgi Apparatus". British Society for Cell Biology. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Lysosome". British Society for Cell Biology. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Karnkowska A, Vacek V, Zubáčová Z, Treitli SC, Petrželková R, Eme L, Novák L, Žárský V, Barlow LD, Herman EK, Soukal P, Hroudová M, Doležal P, Stairs CW, Roger AJ, Eliáš M, Dacks JB, Vlček Č, Hampl V (May 2016). "A Eukaryote without a Mitochondrial Organelle". Current Biology. 26 (10): 1274–1284. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.053. PMID 27185558.

- ^ Siekevitz, Philip (July 1957). "Powerhouse of the Cell". Scientific American. 197 (1): 131–144. Bibcode:1957SciAm.197a.131S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0757-131. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ Mack S (1 May 2006). "Re: Are there eukaryotic cells without mitochondria?". madsci.org. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Watson J, Hopkins N, Roberts J, Steitz JA, Weiner A (1988). "28: The Origins of Life". Molecular Biology of the Gene (Fourth ed.). Menlo Park, CA: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc. p. 1154. ISBN 978-0-8053-9614-0.

- ^ Davis JL (13 May 2016). "Scientists Shocked To Discover Eukaryote With NO Mitochondria". IFL Science. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Sato N (2006). "Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids". In Wise RR, Hoober JK (eds.). The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol. 23. Springer Netherlands. pp. 75–102. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4061-0_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3.

- ^ Margulis L (1998). Symbiotic planet: a new look at evolution. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07271-2. OCLC 39700477.[page needed]

- ^ Lynn Margulis, Heather I. McKhann & Lorraine Olendzenski (ed.), Illustrated Glossary of Protoctista, Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Boston, 1993, p. xviii. ISBN 0-86720-081-2

- ^ Vorobjev IA, Nadezhdina ES (1987). The centrosome and its role in the organization of microtubules. International Review of Cytology. Vol. 106. pp. 227–293. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)61714-3. ISBN 978-0-12-364506-7. PMID 3294718.

- ^ Howland JL (2000). The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-19-511183-5.

- ^ Fry SC (1989). "The Structure and Functions of Xyloglucan". Journal of Experimental Botany. 40 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1093/jxb/40.1.1.

- ^ Raven JA (July 1987). "The role of vacuoles". New Phytologist. 106 (3): 357–422. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb00149.x.

- ^ Oparka K (2005). Plasmodesmata. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ Raven PH, Evert RF, Eichorm SE (1999). Biology of Plants. New York: W.H. Freeman.

- ^ Silflow CD, Lefebvre PA (December 2001). "Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii". Plant Physiology. 127 (4): 1500–1507. doi:10.1104/pp.010807. PMC 1540183. PMID 11743094.

- ^ Deacon J (2005). Fungal Biology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 4 and passim. ISBN 978-1-4051-3066-0.

- ^ Keeling PJ (October 2004). "Diversity and evolutionary history of plastids and their hosts". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1481–1493. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1481. PMID 21652304.

- ^ Patterson DJ. "Amoebae: Protists Which Move and Feed Using Pseudopodia". Tree of Life Web Project. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Lane N (June 2011). "Energetics and genetics across the prokaryote-eukaryote divide". Biology Direct. 6 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-35. PMC 3152533. PMID 21714941.

- ^ Dacks J, Roger AJ (June 1999). "The first sexual lineage and the relevance of facultative sex". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 48 (6): 779–783. Bibcode:1999JMolE..48..779D. doi:10.1007/PL00013156. PMID 10229582. S2CID 9441768.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ramesh MA, Malik SB, Logsdon JM (January 2005). "A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes; evidence for sex in Giardia and an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis". Current Biology. 15 (2): 185–191. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.003. PMID 15668177. S2CID 17013247.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Malik SB, Pightling AW, Stefaniak LM, Schurko AM, Logsdon JM (August 2007). Hahn MW (ed.). "An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides evidence for sex in Trichomonas vaginalis". PLOS ONE. 3 (8): e2879. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2879M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002879. PMC 2488364. PMID 18663385.

- ^ Akopyants NS, Kimblin N, Secundino N, Patrick R, Peters N, Lawyer P, Dobson DE, Beverley SM, Sacks DL (April 2009). "Demonstration of genetic exchange during cyclical development of Leishmania in the sand fly vector". Science. 324 (5924): 265–268. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..265A. doi:10.1126/science.1169464. PMC 2729066. PMID 19359589.

- ^ Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E (July 2011). "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 278 (1715): 2081–2090. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMC 3107637. PMID 21429931.

- ^ Moore RT (1980). "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina. 23: 361–373.

- ^ Goldfuß (1818). "Ueber die Classification der Zoophyten" [On the classification of zoophytes]. Isis, Oder, Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken (in German). 2 (6): 1008–1019. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019. From p. 1008: "Erste Klasse. Urthiere. Protozoa." (First class. Primordial animals. Protozoa.) [Note: each column of each page of this journal is numbered; there are two columns per page.]

- ^ Scamardella JM (1999). "Not plants or animals: a brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista and Protoctista" (PDF). International Microbiology. 2 (4): 207–221. PMID 10943416. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rothschild LJ (1989). "Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?". Journal of the History of Biology. 22 (2): 277–305. doi:10.1007/BF00139515. PMID 11542176. S2CID 32462158. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (June 1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–4579. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Spang A, Saw JH, Jørgensen SL, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Martijn J, Lind AE, van Eijk R, Schleper C, Guy L, Ettema TJ (May 2015). "Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes". Nature. 521 (7551): 173–179. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..173S. doi:10.1038/nature14447. PMC 4444528. PMID 25945739.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Caceres EF, Saw JH, Bäckström D, Juzokaite L, Vancaester E, Seitz KW, Anantharaman K, Starnawski P, Kjeldsen KU, Stott MB, Nunoura T, Banfield JF, Schramm A, Baker BJ, Spang A, Ettema TJ (January 2017). "Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity". Nature. 541 (7637): 353–358. Bibcode:2017Natur.541..353Z. doi:10.1038/nature21031. OSTI 1580084. PMID 28077874. S2CID 4458094. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Liu Y, Zhou Z, Pan J, Baker BJ, Gu JD, Li M (April 2018). "Comparative genomic inference suggests mixotrophic lifestyle for Thorarchaeota". The ISME Journal. 12 (4): 1021–1031. doi:10.1038/s41396-018-0060-x. PMC 5864231. PMID 29445130.

- ^ Adl SM, Simpson AG, Farmer MA, Andersen RA, Anderson OR, Barta JR, et al. (2005). "The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873. S2CID 8060916.

- ^ Harper JT, Waanders E, Keeling PJ (January 2005). "On the monophyly of chromalveolates using a six-protein phylogeny of eukaryotes" (PDF). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 55 (Pt 1): 487–496. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63216-0. PMID 15653923. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008.

- ^ Parfrey LW, Barbero E, Lasser E, Dunthorn M, Bhattacharya D, Patterson DJ, Katz LA (December 2006). "Evaluating support for the current classification of eukaryotic diversity". PLOS Genetics. 2 (12): e220. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020220. PMC 1713255. PMID 17194223.

- ^ Adl SM, Simpson AG, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Bass D, Bowser SS, et al. (September 2012). "The revised classification of eukaryotes" (PDF). The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59 (5): 429–93. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. PMC 3483872. PMID 23020233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Burki F (May 2014). "The eukaryotic tree of life from a global phylogenomic perspective". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (5): a016147. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016147. PMC 3996474. PMID 24789819.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Zhao S, Burki F, Bråte J, Keeling PJ, Klaveness D, Shalchian-Tabrizi K (June 2012). "Collodictyon – an ancient lineage in the tree of eukaryotes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (6): 1557–1568. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss001. PMC 3351787. PMID 22319147.

- ^ Romari K, Vaulot D (2004). "Composition and temporal variability of picoeukaryote communities at a coastal site of the English Channel from 18S rDNA sequences". Limnol Oceanogr. 49 (3): 784–798. Bibcode:2004LimOc..49..784R. doi:10.4319/lo.2004.49.3.0784. S2CID 86718111.

- ^ Roger AJ, Simpson AG (February 2009). "Evolution: revisiting the root of the eukaryote tree". Current Biology. 19 (4): R165–67. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.032. PMID 19243692. S2CID 13172971.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Burki F, Roger AJ, Brown MW, Simpson AG (January 2020). "The New Tree of Eukaryotes". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 35 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008. PMID 31606140.

- ^ Tovar J, Fischer A, Clark CG (June 1999). "The mitosome, a novel organelle related to mitochondria in the amitochondrial parasite Entamoeba histolytica". Molecular Microbiology. 32 (5): 1013–1021. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01414.x. PMID 10361303. S2CID 22805284.

- ^ Boxma B, de Graaf RM, van der Staay GW, van Alen TA, Ricard G, Gabaldón T, van Hoek AH, Moon-van der Staay SY, Koopman WJ, van Hellemond JJ, Tielens AG, Friedrich T, Veenhuis M, Huynen MA, Hackstein JH (March 2005). "An anaerobic mitochondrion that produces hydrogen" (PDF). Nature. 434 (7029): 74–79. Bibcode:2005Natur.434...74B. doi:10.1038/nature03343. PMID 15744302. S2CID 4401178. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Jagus R, Bachvaroff TR, Joshi B, Place AR (2012). "Diversity of Eukaryotic Translational Initiation Factor eIF4E in Protists". Comparative and Functional Genomics. 2012: 1–21. doi:10.1155/2012/134839. PMC 3388326. PMID 22778692.

- ^ Burki F, Kaplan M, Tikhonenkov DV, Zlatogursky V, Minh BQ, Radaykina LV, Smirnov A, Mylnikov AP, Keeling PJ (January 2016). "Untangling the early diversification of eukaryotes: a phylogenomic study of the evolutionary origins of Centrohelida, Haptophyta and Cryptista". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 283 (1823): 20152802. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2802. PMC 4795036. PMID 26817772.

- ^ Janouškovec J, Tikhonenkov DV, Burki F, Howe AT, Rohwer FL, Mylnikov AP, Keeling PJ (December 2017). "A New Lineage of Eukaryotes Illuminates Early Mitochondrial Genome Reduction" (PDF). Current Biology. 27 (23): 3717–24.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.051. PMID 29174886. S2CID 37933928. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Bodył A (February 2018). "Did some red alga-derived plastids evolve via kleptoplastidy? A hypothesis". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 93 (1): 201–222. doi:10.1111/brv.12340. PMID 28544184. S2CID 24613863.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brown MW, Heiss AA, Kamikawa R, Inagaki Y, Yabuki A, Tice AK, Shiratori T, Ishida KI, Hashimoto T, Simpson AG, Roger AJ (February 2018). "Phylogenomics Places Orphan Protistan Lineages in a Novel Eukaryotic Super-Group". Genome Biology and Evolution. 10 (2): 427–433. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy014. PMC 5793813. PMID 29360967.

- ^ Lax G, Eglit Y, Eme L, Bertrand EM, Roger AJ, Simpson AG (November 2018). "Hemimastigophora is a novel supra-kingdom-level lineage of eukaryotes". Nature. 564 (7736): 410–414. Bibcode:2018Natur.564..410L. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0708-8. PMID 30429611. S2CID 205570993.

- ^ Strassert JF, Irisarri I, Williams TA, Burki F (March 2021). "A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 1879. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.1879S. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.08.20.259127. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. PMC 7994803. PMID 33767194. S2CID 221276487.

- ^ Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, et al. (January 2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Schön ME, Zlatogursky VV, Singh RP, Poirier C, Wilken S, Mathur V, et al. (2021). "Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 6651. bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.04.14.439778. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26918-0. PMC 8599508. PMID 34789758. S2CID 233328713.

- ^ Burki F, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Minge M, Skjaeveland A, Nikolaev SI, Jakobsen KS, Pawlowski J (August 2007). Butler G (ed.). "Phylogenomics reshuffles the eukaryotic supergroups". PLOS ONE. 2 (8): e790. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..790B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000790. PMC 1949142. PMID 17726520.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kim E, Graham LE (July 2008). Redfield RJ (ed.). "EEF2 analysis challenges the monophyly of Archaeplastida and Chromalveolata". PLOS ONE. 3 (7): e2621. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2621K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002621. PMC 2440802. PMID 18612431.

- ^ Baurain D, Brinkmann H, Petersen J, Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Stechmann A, Demoulin V, Roger AJ, Burger G, Lang BF, Philippe H (July 2010). "Phylogenomic evidence for separate acquisition of plastids in cryptophytes, haptophytes, and stramenopiles". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 27 (7): 1698–1709. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq059. PMID 20194427.

- ^ Burki F, Okamoto N, Pombert JF, Keeling PJ (June 2012). "The evolutionary history of haptophytes and cryptophytes: phylogenomic evidence for separate origins". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 279 (1736): 2246–2254. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.2301. PMC 3321700. PMID 22298847.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (2006). "Protist phylogeny and the high-level classification of Protozoa". European Journal of Protistology. 39 (4): 338–348. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00002. S2CID 84403388.

- ^ Burki F, Pawlowski J (October 2006). "Monophyly of Rhizaria and multigene phylogeny of unicellular bikonts". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (10): 1922–1930. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl055. PMID 16829542.

- ^ Ren R, Sun Y, Zhao Y, Geiser D, Ma H, Zhou X (September 2016). "Phylogenetic Resolution of Deep Eukaryotic and Fungal Relationships Using Highly Conserved Low-Copy Nuclear Genes". Genome Biology and Evolution. 8 (9): 2683–2701. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw196. PMC 5631032. PMID 27604879.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Cavalier-Smith T (January 2018). "Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences". Protoplasma. 255 (1): 297–357. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3. PMC 5756292. PMID 28875267.

- ^ Derelle R, Torruella G, Klimeš V, Brinkmann H, Kim E, Vlček Č, Lang BF, Eliáš M (February 2015). "Bacterial proteins pinpoint a single eukaryotic root". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (7): E693–699. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E.693D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420657112. PMC 4343179. PMID 25646484.

- ^ Yang J, Harding T, Kamikawa R, Simpson AG, Roger AJ (May 2017). "Mitochondrial Genome Evolution and a Novel RNA Editing System in Deep-Branching Heteroloboseids". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (5): 1161–1174. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx086. PMC 5421314. PMID 28453770.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T, Fiore-Donno AM, Chao E, Kudryavtsev A, Berney C, Snell EA, Lewis R (February 2015). "Multigene phylogeny resolves deep branching of Amoebozoa". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 83: 293–304. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.011. PMID 25150787.

- ^ Torruella G, de Mendoza A, Grau-Bové X, Antó M, Chaplin MA, del Campo J, Eme L, Pérez-Cordón G, Whipps CM, Nichols KM, Paley R, Roger AJ, Sitjà-Bobadilla A, Donachie S, Ruiz-Trillo I (September 2015). "Phylogenomics Reveals Convergent Evolution of Lifestyles in Close Relatives of Animals and Fungi". Current Biology. 25 (18): 2404–2410. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.053. PMID 26365255.

- ^ Jump up to:a b López-García P, Eme L, Moreira D (December 2017). "Symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 434: 20–33. Bibcode:2017JThBi.434...20L. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.02.031. PMC 5638015. PMID 28254477.

- ^ Ponce-Toledo RI, Deschamps P, López-García P, Zivanovic Y, Benzerara K, Moreira D (February 2017). "An Early-Branching Freshwater Cyanobacterium at the Origin of Plastids". Current Biology. 27 (3): 386–391. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.11.056. PMC 5650054. PMID 28132810.

- ^ de Vries J, Archibald JM (February 2017). "Endosymbiosis: Did Plastids Evolve from a Freshwater Cyanobacterium?". Current Biology. 27 (3): R103–105. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.006. PMID 28171752.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cavalier-Smith T (June 2010). "Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree". Biology Letters. 6 (3): 342–345. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0948. PMC 2880060. PMID 20031978.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cavalier-Smith T (May 2013). "Early evolution of eukaryote feeding modes, cell structural diversity, and classification of the protozoan phyla Loukozoa, Sulcozoa, and Choanozoa". European Journal of Protistology. 49 (2): 115–178. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2012.06.001. PMID 23085100.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE, Snell EA, Berney C, Fiore-Donno AM, Lewis R (December 2014). "Multigene eukaryote phylogeny reveals the likely protozoan ancestors of opisthokonts (animals, fungi, choanozoans) and Amoebozoa". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 81: 71–85. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.012. PMID 25152275.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE, Lewis R (April 2018). "Multigene phylogeny and cell evolution of chromist infrakingdom Rhizaria: contrasting cell organisation of sister phyla Cercozoa and Retaria". Protoplasma. 255 (5): 1517–1574. doi:10.1007/s00709-018-1241-1. PMC 6133090. PMID 29666938.

- ^ He D, Fiz-Palacios O, Fu CJ, Fehling J, Tsai CC, Baldauf SL (February 2014). "An alternative root for the eukaryote tree of life". Current Biology. 24 (4): 465–470. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.036. PMID 24508168.

- ^ Cox CJ, Foster PG, Hirt RP, Harris SR, Embley TM (December 2008). "The archaebacterial origin of eukaryotes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (51): 20356–20361. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10520356C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810647105. PMC 2629343. PMID 19073919.

- ^ Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, von Mering C, Creevey CJ, Snel B, Bork P (March 2006). "Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life". Science. 311 (5765): 1283–1287. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1283C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.381.9514. doi:10.1126/science.1123061. PMID 16513982. S2CID 1615592.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hug LA, Baker BJ, Anantharaman K, Brown CT, Probst AJ, Castelle CJ, Butterfield CN, Hernsdorf AW, Amano Y, Ise K, Suzuki Y, Dudek N, Relman DA, Finstad KM, Amundson R, Thomas BC, Banfield JF (April 2016). "A new view of the tree of life". Nature Microbiology. 1 (5): 16048. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.48. PMID 27572647.

- ^ O'Malley MA, Leger MM, Wideman JG, Ruiz-Trillo I (March 2019). "Concepts of the last eukaryotic common ancestor". Nature Ecology & Evolution. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 3 (3): 338–344. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0796-3. hdl:10261/201794. PMID 30778187. S2CID 67790751.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brocks JJ, Logan GA, Buick R, Summons RE (August 1999). "Archean molecular fossils and the early rise of eukaryotes". Science. 285 (5430): 1033–1036. Bibcode:1999Sci...285.1033B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.516.9123. doi:10.1126/science.285.5430.1033. PMID 10446042.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hartman H, Fedorov A (February 2002). "The origin of the eukaryotic cell: a genomic investigation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (3): 1420–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1420H. doi:10.1073/pnas.032658599. PMC 122206. PMID 11805300.

- ^ Knoll AH, Javaux EJ, Hewitt D, Cohen P (June 2006). "Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 361 (1470): 1023–1038. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1843. PMC 1578724. PMID 16754612.

- ^ Retallack GJ, Krull ES, Thackray GD, Parkinson DH (2013). "Problematic urn-shaped fossils from a Paleoproterozoic (2.2 Ga) paleosol in South Africa". Precambrian Research. 235: 71–87. Bibcode:2013PreR..235...71R. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2013.05.015.

- ^ El Albani A, Bengtson S, Canfield DE, Bekker A, Macchiarelli R, Mazurier A, Hammarlund EU, Boulvais P, Dupuy JJ, Fontaine C, Fürsich FT, Gauthier-Lafaye F, Janvier P, Javaux E, Ossa FO, Pierson-Wickmann AC, Riboulleau A, Sardini P, Vachard D, Whitehouse M, Meunier A (July 2010). "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature. 466 (7302): 100–104. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..100A. doi:10.1038/nature09166. PMID 20596019. S2CID 4331375.

- ^ Bengtson S, Belivanova V, Rasmussen B, Whitehouse M (May 2009). "The controversial "Cambrian" fossils of the Vindhyan are real but more than a billion years older". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (19): 7729–7734. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7729B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812460106. PMC 2683128. PMID 19416859.

- ^ Ward P (9 February 2008). "Mass extinctions: the microbes strike back". New Scientist: 40–43. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ French KL, Hallmann C, Hope JM, Schoon PL, Zumberge JA, Hoshino Y, Peters CA, George SC, Love GD, Brocks JJ, Buick R, Summons RE (May 2015). "Reappraisal of hydrocarbon biomarkers in Archean rocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (19): 5915–5920. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5915F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419563112. PMC 4434754. PMID 25918387.

- ^ Brocks, Jochen J.; Jarrett, Amber J. M.; Sirantoine, Eva; Hallmann, Christian; Hoshino, Yosuke; Liyanage, Tharika (August 2017). "The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals". Nature. 548 (7669): 578–581. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..578B. doi:10.1038/nature23457. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28813409. S2CID 205258987.

- ^ Gold, David A.; Caron, Abigail; Fournier, Gregory P.; Summons, Roger E. (March 2017). "Paleoproterozoic sterol biosynthesis and the rise of oxygen". Nature. 543 (7645): 420–423. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..420G. doi:10.1038/nature21412. hdl:1721.1/128450. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28264195. S2CID 205254122.

- ^ Wei, Jeremy H.; Yin, Xinchi; Welander, Paula V. (24 June 2016). "Sterol Synthesis in Diverse Bacteria". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 990. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00990. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4919349. PMID 27446030.

- ^ Hoshino, Yosuke; Gaucher, Eric A. (22 June 2021). "Evolution of bacterial steroid biosynthesis and its impact on eukaryogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (25): e2101276118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101276118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8237579. PMID 34131078.

- ^ Isson TT, Love GD, Dupont CL, Reinhard CT, Zumberge AJ, Asael D, et al. (June 2018). "Tracking the rise of eukaryotes to ecological dominance with zinc isotopes". Geobiology. 16 (4): 341–352. doi:10.1111/gbi.12289. PMID 29869832.

- ^ Yoshikawa G, Blanc-Mathieu R, Song C, Kayama Y, Mochizuki T, Murata K, Ogata H, Takemura M (April 2019). "Medusavirus, a Novel Large DNA Virus Discovered from Hot Spring Water". Journal of Virology. 93 (8). doi:10.1128/JVI.02130-18. PMC 6450098. PMID 30728258. Archived from the original on 30 April 2019.

- "New giant virus may help scientists better understand the emergence of complex life". EurekAlert! (Press release). 30 April 2019.

- ^ Martin W (December 2005). "Archaebacteria (Archaea) and the origin of the eukaryotic nucleus". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 8 (6): 630–637. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.004. PMID 16242992.

- ^ Takemura M (May 2001). "Poxviruses and the origin of the eukaryotic nucleus". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 52 (5): 419–425. Bibcode:2001JMolE..52..419T. doi:10.1007/s002390010171. PMID 11443345. S2CID 21200827.

- ^ Bell PJ (September 2001). "Viral eukaryogenesis: was the ancestor of the nucleus a complex DNA virus?". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 53 (3): 251–256. Bibcode:2001JMolE..53..251L. doi:10.1007/s002390010215. PMID 11523012. S2CID 20542871.

- ^ Wächtershäuser G (January 2003). "From pre-cells to Eukarya – a tale of two lipids". Molecular Microbiology. 47 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03267.x. PMID 12492850. S2CID 37944519.

- ^ Wächtershäuser G (October 2006). "From volcanic origins of chemoautotrophic life to Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 361 (1474): 1787–1806, discussion 1806–1808. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1904. PMC 1664677. PMID 17008219.

- ^ Lane N (2016). The Vital Question: Why is Life the Way it is? (paperback ed.). Profile Books. pp. 157–91. ISBN 978-1-781-25037-2.

- ^ Egel R (January 2012). "Primal eukaryogenesis: on the communal nature of precellular States, ancestral to modern life". Life. Vol. 2, no. 1. pp. 170–212. doi:10.3390/life2010170. PMC 4187143. PMID 25382122.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Harish A, Tunlid A, Kurland CG (August 2013). "Rooted phylogeny of the three superkingdoms". Biochimie. 95 (8): 1593–1604. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2013.04.016. PMID 23669449.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Harish A, Kurland CG (July 2017). "Akaryotes and Eukaryotes are independent descendants of a universal common ancestor". Biochimie. 138: 168–183. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2017.04.013. PMID 28461155.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Imachi H, Nobu MK, Nakahara N, Morono Y, Ogawara M, Takaki Y, et al. (January 2020). "Isolation of an archaeon at the prokaryote-eukaryote interface". Nature. 577 (7791): 519–525. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..519I. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1916-6. PMC 7015854. PMID 31942073.

- ^ Da Cunha V, Gaia M, Gadelle D, Nasir A, Forterre P (June 2017). "Lokiarchaea are close relatives of Euryarchaeota, not bridging the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes". PLOS Genetics. 13 (6): e1006810. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006810. PMC 5484517. PMID 28604769.

- ^ Harish A, Kurland CG (July 2017). "Empirical genome evolution models root the tree of life". Biochimie. 138: 137–155. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2017.04.014. PMID 28478110.

- ^ Spang A, Eme L, Saw JH, Caceres EF, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Lombard J, et al. (March 2018). "Asgard archaea are the closest prokaryotic relatives of eukaryotes". PLOS Genetics. 14 (3): e1007080. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007080. PMC 5875740. PMID 29596421.

- ^ MacLeod F, Kindler GS, Wong HL, Chen R, Burns BP (2019). "Asgard archaea: Diversity, function, and evolutionary implications in a range of microbiomes". AIMS Microbiology. 5 (1): 48–61. doi:10.3934/microbiol.2019.1.48. PMC 6646929. PMID 31384702.

- ^ Zimmer C (15 January 2020). "This Strange Microbe May Mark One of Life's Great Leaps – A organism living in ocean muck offers clues to the origins of the complex cells of all animals and plants". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Jékely G (2007). "Origin of Eukaryotic Endomembranes: A Critical Evaluation of Different Model Scenarios". Eukaryotic Membranes and Cytoskeleton. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 607. New York, N.Y. : Springer Science+Business Media; Austin, Tex. : Landes Bioscience. pp. 38–51. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74021-8_3. ISBN 978-0-387-74020-1. PMID 17977457.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (March 2002). "The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 52 (Pt 2): 297–354. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-2-297. PMID 11931142. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Martin W, Müller M (March 1998). "The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote". Nature. 392 (6671): 37–41. Bibcode:1998Natur.392...37M. doi:10.1038/32096. PMID 9510246. S2CID 338885.

- ^ Pisani D, Cotton JA, McInerney JO (August 2007). "Supertrees disentangle the chimerical origin of eukaryotic genomes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (8): 1752–1760. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm095. PMID 17504772.

- ^ Brueckner J, Martin WF (April 2020). "Bacterial Genes Outnumber Archaeal Genes in Eukaryotic Genomes". Genome Biology and Evolution. 12 (4): 282–292. doi:10.1093/gbe/evaa047. PMC 7151554. PMID 32142116.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Latorre A, Durban A, Moya A, Pereto J (2011). "The role of symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution". In Gargaud M, López-Garcìa P, Martin H (eds.). Origins and Evolution of Life: An astrobiological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 326–339. ISBN 978-0-521-76131-4. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Ayala J (April 1994). "Transport and internal organization of membranes: vesicles, membrane networks and GTP-binding proteins". Journal of Cell Science. 107 ( Pt 4) (107): 753–763. doi:10.1242/jcs.107.4.753. PMID 8056835. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Martin WF. "The Origin of Mitochondria". Scitable. Nature education. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Dacks JB, Field MC (August 2018). "Evolutionary origins and specialisation of membrane transport". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 53: 70–76. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2018.06.001. PMC 6141808. PMID 29929066.

- ^ Martijn J, Vosseberg J, Guy L, Offre P, Ettema TJ (May 2018). "Deep mitochondrial origin outside the sampled alphaproteobacteria". Nature. 557 (7703): 101–105. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..101M. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0059-5. PMID 29695865. S2CID 13740626. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Shawna Williams (25 April 2018). "Mitochondria's Bacterial Origins Upended". The Scientist.

- ^ Baum DA, Baum B (October 2014). "An inside-out origin for the eukaryotic cell". BMC Biology. 12: 76. doi:10.1186/s12915-014-0076-2. PMC 4210606. PMID 25350791.

- Terry Devitt (12 December 2014). "New theory suggests alternate path led to rise of the eukaryotic cell". University of Wisconsin-Madison (Press release). Archived from the original on 21 April 2019.

- ^ Brouwers L (12 April 2013). "How genetic plunder transformed a microbe into a pink, salt-loving scavenger". Scientific American. 109 (50): 20537–20542. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Wilcox, C (9 April 2019). "Rethinking the ancestry of the eukaryotes". Quanta Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ McCutcheon, JP (6 October 2021). "The Genomics and Cell Biology of Host-Beneficial Intracellular Infections". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 37 (1): 115–142. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-120219-024122. ISSN 1081-0706. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Callier, V (8 June 2022). "Mitochondria and the origin of eukaryotes". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-060822-2. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ Pittis AA, Gabaldón T (March 2016). "Late acquisition of mitochondria by a host with chimaeric prokaryotic ancestry". Nature. 531 (7592): 101–104. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..101P. doi:10.1038/nature16941. PMC 4780264. PMID 26840490.

- ^ Burton ZF (1 August 2017). Evolution since coding: Cradles, halos, barrels, and wings. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-813034-6. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Martin WF, Roettger M, Ku C, Garg SG, Nelson-Sathi S, Landan G (February 2017). "Late mitochondrial origin is an artifact". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (2): 373–379. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx027. PMC 5516564. PMID 28199635.

This article incorporates public domain material from the NCBI document: "Science Primer".

외부 링크[편집]

- "진핵생물"(생명의 나무 웹 프로젝트)

- 생명의 백과사전에서 "유카리오테"

- 우리의 미생물 사이의 매력과 섹스 마지막 진핵 공통 조상, 대서양, 11 월 11, 2020

'생명공학' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 고세균Archaebacteria (0) | 2022.09.21 |

|---|---|

| 생명 (0) | 2022.09.21 |

| 접합자 zygote (0) | 2022.09.21 |

| 식물생리학 -plant physiology (0) | 2022.09.03 |

| 식물생리학 (0) | 2022.09.03 |