일반적으로 당뇨병으로 알려진 당뇨병은 장기간에 걸쳐 높은 혈당 수준 (고혈당증)을 특징으로하는 대사 장애 그룹입니다. [12] 증상은 종종 빈번한 배뇨, 갈증 증가 및 식욕 증가를 포함한다. [2] 치료하지 않고 방치하면 당뇨병은 많은 건강 합병증을 일으킬 수 있습니다. [2] 급성 합병증에는 당뇨병성 케톤산증, 고삼투압 고혈당 상태 또는 사망이 포함될 수 있다. [3] 심각한 장기 합병증에는 심혈관 질환, 뇌졸중, 만성 신장 질환, 족부 궤양, 신경 손상, 눈 손상 및인지 장애가 포함됩니다. [2][5]

당뇨병발음전문조짐합병증위험 요인진단 방법치료약물 치료빈도죽음| 당뇨병에 대한 유니버설 블루 서클 기호[1] | |

| 내분비학 | |

| 당뇨병성 케톤산증, 고삼투압 고혈당 상태, 심장 질환, 뇌졸중, 손과 발의 통증/핀 및 바늘, 만성 신부전, 족부 궤양, 인지 장애, 위마비[2][3][4][5] | |

| 유형 1 : 가족력[6]유형 2 : 비만, 운동 부족, 유전학,[2][7] 대기 오염[8] | |

| 고혈당[2] | |

| 인슐린, 메트포르민과 같은 항당뇨제[2][9][10] | |

| 463 백만 (8.8 %)[11] | |

| 4.2 백만 (2019)[11] | |

당뇨병은 췌장이 충분한 인슐린을 생산하지 못하거나 신체의 세포가 생산 된 인슐린에 제대로 반응하지 않기 때문입니다. [13] 인슐린은 음식에서 포도당이 에너지에 사용되는 세포에 들어가는 것을 돕는 역할을 하는 호르몬입니다. [14] 당뇨병의 세 가지 주요 유형이 있습니다 :[2]

- 제 1 형 당뇨병은 베타 세포의 손실로 인해 충분한 인슐린을 생산하지 못하는 췌장의 실패로 인해 발생합니다. [2] 이 형태는 이전에 "인슐린 의존성 당뇨병" 또는 "청소년 당뇨병"으로 불렸다. [2] 베타 세포의 손실은 자가면역 반응에 의해 유발된다. [15] 이 자가면역 반응의 원인은 알려져 있지 않다. [2] 제 1 형 당뇨병은 일반적으로 어린 시절이나 청소년기에 나타나지만 성인에서도 발생할 수 있습니다. [16]

- 제 2 형 당뇨병은 세포가 인슐린에 제대로 반응하지 못하는 상태 인 인슐린 저항성으로 시작됩니다. [2] 질병이 진행됨에 따라 인슐린 부족도 발생할 수 있습니다. [17] 이 형태는 이전에 "인슐린 비의존성 당뇨병" 또는 "성인-발병 당뇨병"으로 지칭되었다. [2] 제 2 형 당뇨병은 고령자에서 더 흔하지만, 아이들 사이에서 비만의 유병률이 크게 증가하여 젊은 사람들에게 제 2 형 당뇨병의 사례가 더 많아졌습니다. [18] 가장 흔한 원인은 과도한 체중과 불충분 한 운동의 조합입니다. [2]

- 임신성 당뇨병은 세 번째 주요 형태이며, 당뇨병의 이전 병력이없는 임산부가 높은 혈당 수치를 개발할 때 발생합니다. [2] 임신성 당뇨병을 앓고있는 여성의 경우, 혈당은 보통 출산 직후에 정상으로 돌아갑니다. 그러나 임신 중에 임신성 당뇨병을 앓은 여성은 나중에 제 2 형 당뇨병을 일으킬 위험이 더 큽니다. [19]

제 1 형 당뇨병은 인슐린 주사로 관리해야합니다. [2] 제 2 형 당뇨병의 예방 및 치료는 건강한식이 요법, 정기적 인 신체 운동, 정상적인 체중을 유지하고 담배 사용을 피하는 것을 포함합니다. [2] 제 2 형 당뇨병은 인슐린 유무에 관계없이 경구 용 항 당뇨병 약물로 치료할 수 있습니다. [20] 혈압을 조절하고 적절한 발과 안과 관리를 유지하는 것은 질병을 앓고있는 사람들에게 중요합니다. [2] 인슐린 및 일부 경구 약물은 저혈당 (저혈당)을 일으킬 수 있습니다. [21] 비만 환자의 체중 감량 수술은 때때로 제 2 형 당뇨병 환자에게 효과적인 척도입니다. [22] 임신성 당뇨병은 보통 아기의 출생 후에 해결된다. [23]

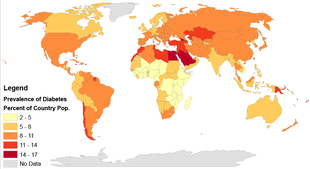

2019년 기준전 세계적으로 약 463 만 명이 당뇨병을 앓고 있으며 (성인 인구의 8.8 %), 제 2 형 당뇨병이 사례의 약 90 %를 차지합니다. [11] 비율은 여자와 남자에서 유사하다. [24] 동향은 금리가 계속 상승 할 것이라고 제안합니다. [11] 당뇨병은 적어도 사람의 조기 사망 위험을 두 배로 증가시킵니다. [2] 2019에서 당뇨병은 약 4.2 백만 명의 사망자를 초래했습니다. [11] 그것은 전 세계적으로 사망의 7 번째 주요 원인입니다. [25][26] 2017년 당뇨병 관련 건강 지출의 세계 경제 비용은 미화 7270억 달러로 추산되었다. [11] 미국에서 당뇨병은 2017 년에 거의 US $ 327 billion의 비용이 들었습니다. [27] 당뇨병 환자의 평균 의료 지출은 약 2.3 배 높습니다. [28]

목차

징후와 증상편집하다

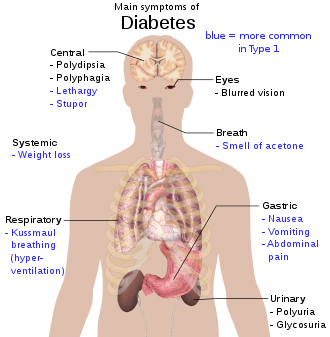

치료되지 않은 당뇨병의 고전적인 증상은 의도하지 않은 체중 감소, 다뇨증 (배뇨 증가), polydipsia (갈증 증가) 및 다식증 (굶주림 증가)입니다. [29] 증상은 제 1 형 당뇨병에서 급속히 (몇 주 또는 몇 달) 발전 할 수 있지만, 일반적으로 훨씬 천천히 진행되며 제 2 형 당뇨병에서는 미묘하거나 결석 할 수 있습니다. [30]

몇 가지 다른 징후와 증상은 당뇨병의 발병을 표시 할 수 있지만 질병에만 국한되지는 않습니다. 위에 나열된 알려진 증상 외에도 시력 저하, 두통, 피로, 상처의 느린 치유 및 가려운 피부가 포함됩니다. 장기간의 고혈당은 눈의 수정체에 포도당 흡수를 일으켜 모양이 변화하여 시력 변화를 일으킬 수 있습니다. 장기간의 시력 손실은 또한 당뇨병성 망막병증에 의해 야기될 수 있다. 당뇨병에서 발생할 수 있는 다수의 피부 발진은 집합적으로 당뇨병성 dermadromes로 알려져 있다. [31]

당뇨병 응급 상황편집하다

당뇨병을 앓고있는 사람들 (일반적으로 제 1 형 당뇨병에서만 독점적으로 발생하지는 않음)은 메스꺼움, 구토 및 복통, 호흡시 아세톤 냄새, Kussmaul 호흡으로 알려진 심호흡, 심한 경우 의식 수준 감소를 특징으로하는 대사 장애 인 당뇨병 성 케톤 산증 (DKA)을 경험할 수 있습니다. DKA는 병원에서 응급 치료가 필요합니다. [32] 드물지만 더 위험한 상태는 고삼투압 고혈당 상태 (HHS)이며, 이는 제 2 형 당뇨병에서 더 흔하며 주로 고혈당으로 인한 탈수의 결과입니다. [32]

치료 관련 저혈당 (저혈당)은 사용되는 약물에 따라 제 1 형 및 제 2 형 당뇨병 환자에게 일반적입니다. 대부분의 경우는 경미하며 의료 응급 상황으로 간주되지 않습니다. 효과는 경미한 경우 불안감, 발한, 떨림, 식욕 증가에 이르기까지 혼란, 공격성, 발작, 무의식과 같은 행동 변화, 심한 경우에는 드물게 영구적 인 뇌 손상이나 사망과 같은 더 심각한 영향에 이르기까지 다양합니다. [33][34] 빠른 호흡, 발한, 차갑고 창백한 피부는 저혈당의 특징이지만 결정적이지는 않습니다. [35] 경증에서 중등도의 경우는 빠르게 흡수되는 탄수화물이 많이 섭취하거나 음주로 스스로 치료됩니다. 심한 경우 무의식으로 이어질 수 있으며 정맥 내 포도당 또는 글루카곤 주사로 치료해야합니다. [36]

합병증편집하다

모든 형태의 당뇨병은 장기적인 합병증의 위험을 증가시킵니다. 이들은 일반적으로 수년 (10-20) 후에 발생하지만 그 전에 진단을받지 못한 사람들의 첫 번째 증상 일 수 있습니다. [37]

주요 장기 합병증은 혈관 손상과 관련이 있습니다. 당뇨병은 심혈관 질환의 위험을 두 배로 증가시키며[38] 당뇨병 환자의 사망률의 약 75%는 관상동맥 질환으로 인한 것입니다. [39] 다른 대혈관 질환은 뇌졸중, 및 말초 동맥 질환을 포함한다. [40] 이러한 합병증은 또한 심각한 COVID-19 질병에 대한 강력한 위험 요소입니다. [41]

작은 혈관의 손상으로 인한 당뇨병의 주요 합병증에는 눈, 신장 및 신경 손상이 포함됩니다. [42] 당뇨병성 망막증으로 알려진 눈의 손상은 눈의 망막에 있는 혈관의 손상에 의해 야기되고, 점진적인 시력 상실 및 최후의 실명을 초래할 수 있다. [42] 당뇨병은 또한 녹내장, 백내장 및 기타 눈 문제를 가질 위험을 증가시킨다. 당뇨병 환자는 일년에 한 번 안과 의사를 방문하는 것이 좋습니다. [43] 당뇨병성 신증으로 알려진 신장의 손상은 조직 흉터, 소변 단백질 손실 및 결국 만성 신장 질환으로 이어질 수 있으며 때로는 투석 또는 신장 이식이 필요합니다. [42] 당뇨병 성 신경 병증으로 알려진 신체의 신경 손상은 당뇨병의 가장 흔한 합병증입니다. [42] 증상은 마비, 따끔 거림, sudomotor 기능 장애, 통증 및 피부 손상으로 이어질 수있는 통증 감각을 포함 할 수 있습니다. 당뇨병 관련 발 문제 (예 : 당뇨병 성 족부 궤양)가 발생할 수 있으며 치료가 어려울 수 있으며 때로는 절단이 필요할 수 있습니다. 또한, 근위 당뇨병 성 신경 병증은 고통스러운 근육 위축과 약점을 유발합니다.

인지 결핍과 당뇨병 사이에는 연관성이 있습니다. 당뇨병이없는 사람들과 비교했을 때,이 질병을 앓고있는 사람들은인지 기능 저하율이 1.2 ~ 1.5 배 더 큽니다. [44] 당뇨병을 앓고, 특히 인슐린을 복용 할 때 노인의 낙상 위험이 증가합니다. [45]

CausesEdit

Comparison of type 1 and 2 diabetes[46]FeatureType 1 diabetesType 2 diabetesOnsetAge at onsetBody sizeKetoacidosisAutoantibodiesEndogenous insulinHeritabilityPrevalence(age standardized)| Sudden | Gradual |

| Mostly in children | Mostly in adults |

| Thin or normal[47] | Often obese |

| Common | Rare |

| Usually present | Absent |

| Low or absent | Normal, decreased or increased |

| 0.69 to 0.88[48][49][50] | 0.47 to 0.77[51] |

| <2 per 1,000[52][53] | ~6% (men), ~5% (women)[54] |

Diabetes mellitus is classified into six categories: type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, hybrid forms of diabetes, hyperglycemia first detected during pregnancy, "unclassified diabetes", and "other specific types".[55] "Hybrid forms of diabetes" include slowly evolving, immune-mediated diabetes of adults and ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes. "Hyperglycemia first detected during pregnancy" includes gestational diabetes mellitus and diabetes mellitus in pregnancy (type 1 or type 2 diabetes first diagnosed during pregnancy). The "other specific types" are a collection of a few dozen individual causes. Diabetes is a more variable disease than once thought and people may have combinations of forms.[56]

Type 1Edit

Type 1 diabetes is characterized by loss of the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreatic islets, leading to insulin deficiency. This type can be further classified as immune-mediated or idiopathic. The majority of type 1 diabetes is of an immune-mediated nature, in which a T cell-mediated autoimmune attack leads to the loss of beta cells and thus insulin.[57] It causes approximately 10% of diabetes mellitus cases in North America and Europe. Most affected people are otherwise healthy and of a healthy weight when onset occurs. Sensitivity and responsiveness to insulin are usually normal, especially in the early stages. Although it has been called "juvenile diabetes" due to the frequent onset in children, the majority of individuals living with type 1 diabetes are now adults.[6]

"Brittle" diabetes, also known as unstable diabetes or labile diabetes, is a term that was traditionally used to describe the dramatic and recurrent swings in glucose levels, often occurring for no apparent reason in insulin-dependent diabetes. This term, however, has no biologic basis and should not be used.[58] Still, type 1 diabetes can be accompanied by irregular and unpredictable high blood sugar levels, and the potential for diabetic ketoacidosis or serious low blood sugar levels. Other complications include an impaired counterregulatory response to low blood sugar, infection, gastroparesis (which leads to erratic absorption of dietary carbohydrates), and endocrinopathies (e.g., Addison's disease).[58] These phenomena are believed to occur no more frequently than in 1% to 2% of persons with type 1 diabetes.[59]

Type 1 diabetes is partly inherited, with multiple genes, including certain HLA genotypes, known to influence the risk of diabetes. In genetically susceptible people, the onset of diabetes can be triggered by one or more environmental factors,[60] such as a viral infection or diet. Several viruses have been implicated, but to date there is no stringent evidence to support this hypothesis in humans.[60][61] Among dietary factors, data suggest that gliadin (a protein present in gluten) may play a role in the development of type 1 diabetes, but the mechanism is not fully understood.[62][63]

Type 1 diabetes can occur at any age, and a significant proportion is diagnosed during adulthood. Latent autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA) is the diagnostic term applied when type 1 diabetes develops in adults; it has a slower onset than the same condition in children. Given this difference, some use the unofficial term "type 1.5 diabetes" for this condition. Adults with LADA are frequently initially misdiagnosed as having type 2 diabetes, based on age rather than a cause.[64]

Type 2Edit

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by insulin resistance, which may be combined with relatively reduced insulin secretion.[13] The defective responsiveness of body tissues to insulin is believed to involve the insulin receptor. However, the specific defects are not known. Diabetes mellitus cases due to a known defect are classified separately. Type 2 diabetes is the most common type of diabetes mellitus.[2] Many people with type 2 diabetes have evidence of prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance) before meeting the criteria for type 2 diabetes.[65] The progression of prediabetes to overt type 2 diabetes can be slowed or reversed by lifestyle changes or medications that improve insulin sensitivity or reduce the liver's glucose production.[66]

Type 2 diabetes is primarily due to lifestyle factors and genetics.[67] A number of lifestyle factors are known to be important to the development of type 2 diabetes, including obesity (defined by a body mass index of greater than 30), lack of physical activity, poor diet, stress, and urbanization.[46] Excess body fat is associated with 30% of cases in people of Chinese and Japanese descent, 60–80% of cases in those of European and African descent, and 100% of Pima Indians and Pacific Islanders.[13] Even those who are not obese may have a high waist–hip ratio.[13]

Dietary factors such as sugar-sweetened drinks are associated with an increased risk.[68][69] The type of fats in the diet is also important, with saturated fat and trans fats increasing the risk and polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat decreasing the risk.[67] Eating white rice excessively may increase the risk of diabetes, especially in Chinese and Japanese people.[70] Lack of physical activity may increase the risk of diabetes in some people.[71]

Adverse childhood experiences, including abuse, neglect, and household difficulties, increase the likelihood of type 2 diabetes later in life by 32%, with neglect having the strongest effect.[72]

Antipsychotic medication side effects (specifically metabolic abnormalities, dyslipidemia and weight gain) and unhealthy lifestyles (including poor diet and decreased physical activity), are potential risk factors.[73]

Gestational diabetesEdit

Gestational diabetes resembles type 2 diabetes in several respects, involving a combination of relatively inadequate insulin secretion and responsiveness. It occurs in about 2–10% of all pregnancies and may improve or disappear after delivery.[74] It is recommended that all pregnant women get tested starting around 24–28 weeks gestation.[75] It is most often diagnosed in the second or third trimester because of the increase in insulin-antagonist hormone levels that occurs at this time.[75] However, after pregnancy approximately 5–10% of women with gestational diabetes are found to have another form of diabetes, most commonly type 2.[74] Gestational diabetes is fully treatable, but requires careful medical supervision throughout the pregnancy. Management may include dietary changes, blood glucose monitoring, and in some cases, insulin may be required.[76]

Though it may be transient, untreated gestational diabetes can damage the health of the fetus or mother. Risks to the baby include macrosomia (high birth weight), congenital heart and central nervous system abnormalities, and skeletal muscle malformations. Increased levels of insulin in a fetus's blood may inhibit fetal surfactant production and cause infant respiratory distress syndrome. A high blood bilirubin level may result from red blood cell destruction. In severe cases, perinatal death may occur, most commonly as a result of poor placental perfusion due to vascular impairment. Labor induction may be indicated with decreased placental function. A caesarean section may be performed if there is marked fetal distress[77] or an increased risk of injury associated with macrosomia, such as shoulder dystocia.[78]

Other typesEdit

Maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a rare autosomal dominant inherited form of diabetes, due to one of several single-gene mutations causing defects in insulin production.[79] It is significantly less common than the three main types, constituting 1–2% of all cases. The name of this disease refers to early hypotheses as to its nature. Being due to a defective gene, this disease varies in age at presentation and in severity according to the specific gene defect; thus, there are at least 13 subtypes of MODY. People with MODY often can control it without using insulin.[80]

Some cases of diabetes are caused by the body's tissue receptors not responding to insulin (even when insulin levels are normal, which is what separates it from type 2 diabetes); this form is very uncommon. Genetic mutations (autosomal or mitochondrial) can lead to defects in beta cell function. Abnormal insulin action may also have been genetically determined in some cases. Any disease that causes extensive damage to the pancreas may lead to diabetes (for example, chronic pancreatitis and cystic fibrosis). Diseases associated with excessive secretion of insulin-antagonistic hormones can cause diabetes (which is typically resolved once the hormone excess is removed). Many drugs impair insulin secretion and some toxins damage pancreatic beta cells, whereas others increase insulin resistance (especially glucocorticoids which can provoke "steroid diabetes"). The ICD-10 (1992) diagnostic entity, malnutrition-related diabetes mellitus (ICD-10 code E12), was deprecated by the World Health Organization (WHO) when the current taxonomy was introduced in 1999.[81] Yet another form of diabetes that people may develop is double diabetes. This is when a type 1 diabetic becomes insulin resistant, the hallmark for type 2 diabetes or has a family history for type 2 diabetes.[82] It was first discovered in 1990 or 1991.

The following is a list of disorders that may increase the risk of diabetes:[83]

- Genetic defects of β-cell function

- Maturity onset diabetes of the young

- Mitochondrial DNA mutations

- Genetic defects in insulin processing or insulin action

- Defects in proinsulin conversion

- Insulin gene mutations

- Insulin receptor mutations

- Exocrine pancreatic defects (see Type 3c diabetes, i.e. pancreatogenic diabetes)

- Endocrinopathies

- Growth hormone excess (acromegaly)

- Cushing syndrome

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypothyroidism

- Pheochromocytoma

- Glucagonoma

- Infections

- Drugs

PathophysiologyEdit

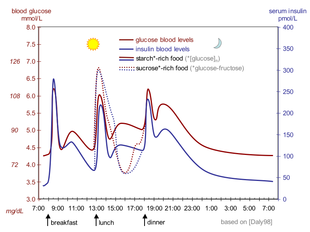

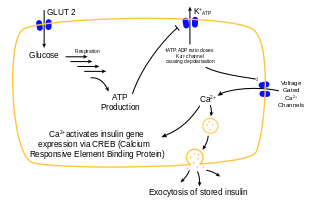

Insulin is the principal hormone that regulates the uptake of glucose from the blood into most cells of the body, especially liver, adipose tissue and muscle, except smooth muscle, in which insulin acts via the IGF-1.[citation needed] Therefore, deficiency of insulin or the insensitivity of its receptors play a central role in all forms of diabetes mellitus.[85]

The body obtains glucose from three main sources: the intestinal absorption of food; the breakdown of glycogen (glycogenolysis), the storage form of glucose found in the liver; and gluconeogenesis, the generation of glucose from non-carbohydrate substrates in the body.[86] Insulin plays a critical role in regulating glucose levels in the body. Insulin can inhibit the breakdown of glycogen or the process of gluconeogenesis, it can stimulate the transport of glucose into fat and muscle cells, and it can stimulate the storage of glucose in the form of glycogen.[86]

Insulin is released into the blood by beta cells (β-cells), found in the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, in response to rising levels of blood glucose, typically after eating. Insulin is used by about two-thirds of the body's cells to absorb glucose from the blood for use as fuel, for conversion to other needed molecules, or for storage. Lower glucose levels result in decreased insulin release from the beta cells and in the breakdown of glycogen to glucose. This process is mainly controlled by the hormone glucagon, which acts in the opposite manner to insulin.[87]

If the amount of insulin available is insufficient, or if cells respond poorly to the effects of insulin (insulin resistance), or if the insulin itself is defective, then glucose is not absorbed properly by the body cells that require it, and is not stored appropriately in the liver and muscles. The net effect is persistently high levels of blood glucose, poor protein synthesis, and other metabolic derangements, such as metabolic acidosis in cases of complete insulin deficiency.[86]

When glucose concentration in the blood remains high over time, the kidneys reach a threshold of reabsorption, and the body excretes glucose in the urine (glycosuria).[88] This increases the osmotic pressure of the urine and inhibits reabsorption of water by the kidney, resulting in increased urine production (polyuria) and increased fluid loss. Lost blood volume is replaced osmotically from water in body cells and other body compartments, causing dehydration and increased thirst (polydipsia).[86] In addition, intracellular glucose deficiency stimulates appetite leading to excessive food intake (polyphagia).[89]

DiagnosisEdit

Diabetes mellitus is diagnosed with a test for the glucose content in the blood, and is diagnosed by demonstrating any one of the following:[81]

- Fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL). For this test, blood is taken after a period of fasting, i.e. in the morning before breakfast, after the patient had sufficient time to fast overnight.

- Plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) two hours after a 75 gram oral glucose load as in a glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

- Symptoms of high blood sugar and plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) either while fasting or not fasting

- Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) ≥ 48 mmol/mol (≥ 6.5 DCCT %).[90]

| Unit | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/mol | DCCT % |

| 보통 | < 7.8 | < 140 | < 6.1 | < 110 | < 42 | < 6.0 |

| 공복 혈당 장애 | < 7.8 | < 140 | 6.1–7.0 | 110–125 | 42–46 | 6.0–6.4 |

| 내당능 장애 | ≥ 7.8 | ≥ 140 | < 7.0 | < 126 | 42–46 | 6.0–6.4 |

| 당뇨병 | ≥ 11.1 | ≥ 200 | ≥ 7.0 | ≥ 126 | ≥ 48 | ≥ 6.5 |

명백한 고혈당이없는 경우 긍정적 인 결과는 다른 날에 위의 방법 중 하나를 반복하여 확인해야합니다. 측정의 용이성과 공식적인 포도당 내성 테스트의 상당한 시간 투입으로 인해 공복 포도당 수준을 측정하는 것이 바람직한데, 이는 완료하는 데 두 시간이 걸리고 공복 검사에 비해 예후 이점을 제공하지 않습니다. [93] 현재 정의에 따르면, 7.0 mmol / L (126 mg / dL) 이상의 두 개의 공복 포도당 측정은 당뇨병 진단으로 간주됩니다.

WHO에 따르면, 공복 혈당 수치가 6.1 ~ 6.9 mmol / L (110 ~ 125 mg / dL)인 사람들은 공복 포도당이 손상된 것으로 간주됩니다. [94] 혈장 포도당이 7.8 mmol / L (140 mg / dL) 이상이지만 11.1 mmol / L (200 mg / dL)을 넘지 않는 사람들은 75 그램의 경구 포도당 부하가 발생한 후 2 시간 후에 내당능이 손상된 것으로 간주됩니다. 이 두 가지 당뇨병 전 상태 중 후자는 특히 심혈관 질환뿐만 아니라 본격적인 당뇨병으로 진행하기위한 주요 위험 요소입니다. [95] 2003 년부터 미국 당뇨병 협회 (ADA)는 5.6 ~ 6.9 mmol / L (100 ~ 125 mg / dL)의 공복 혈당 장애에 대해 약간 다른 범위를 사용합니다. [96]

당화 헤모글로빈은 심혈관 질환 및 모든 원인으로 인한 사망의 위험을 결정하기 위해 공복 포도당보다 낫습니다. [97]

예방편집하다

제 1 형 당뇨병에 대한 알려진 예방 조치는 없습니다. [2] 전 세계 모든 사례의 85-90 %를 차지하는 제 2 형 당뇨병은 정상적인 체중을 유지하고 신체 활동에 참여하며 건강한 식단을 섭취함으로써 종종 예방되거나 지연 될 수 있습니다 [98]. [2] 높은 수준의 신체 활동 (하루 90 분 이상)은 당뇨병의 위험을 28 % 감소시킵니다. [99] 당뇨병을 예방하는 데 효과적인 것으로 알려진식이 변화에는 전체 곡물과 섬유질이 풍부한 식단을 유지하고 견과류, 식물성 기름 및 생선에서 발견되는 고도 불포화 지방과 같은 좋은 지방을 선택하는 것이 포함됩니다. [100] 설탕 음료를 제한하고 붉은 고기와 포화 지방의 다른 소스를 적게 먹으면 당뇨병을 예방하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다. [100] 담배 흡연은 또한 당뇨병 및 합병증의 위험 증가와 관련이 있으므로 금연은 중요한 예방 조치가 될 수 있습니다. [101]

제 2 형 당뇨병과 주요 수정 가능한 위험 요소 (과체중, 건강에 해로운 식단, 신체 활동이없는 음식 및 담배 사용) 사이의 관계는 전 세계 모든 지역에서 유사합니다. 당뇨병의 근본적인 결정 요인이 세계화, 도시화, 인구 고령화 및 일반 건강 정책 환경과 같은 사회적, 경제적, 문화적 변화를 주도하는 주요 세력을 반영한다는 증거가 증가하고 있습니다. [102]

경영편집하다

Diabetes management concentrates on keeping blood sugar levels as close to normal, without causing low blood sugar. This can usually be accomplished with dietary changes,[103] exercise, weight loss, and use of appropriate medications (insulin, oral medications).

Learning about the disease and actively participating in the treatment is important, since complications are far less common and less severe in people who have well-managed blood sugar levels.[104][105] Per the American College of Physicians, the goal of treatment is an HbA1C level of 7-8%.[106] Attention is also paid to other health problems that may accelerate the negative effects of diabetes. These include smoking, high blood pressure, metabolic syndrome obesity, and lack of regular exercise.[107] Specialized footwear is widely used to reduce the risk of ulcers in at-risk diabetic feet although evidence for the efficacy of this remains equivocal.[108]

The principles of managing diabetes may be similar across the general population with diabetes, however some considerations may need to be addressed when tailoring intervention, mainly in special populations.

심각한 정신 질환을 앓고있는 사람들을 고려할 때, 제 2 형 당뇨병 자기 관리 중재의 효능은 여전히 제대로 탐구되지 않았으며, 이러한 개입이 일반 인구에서 관찰 된 것과 유사한 결과를 가지고 있는지 여부를 보여주는 과학적 증거가 충분하지 않습니다. [109]

생활방식편집하다

당뇨병을 앓고있는 사람들은 단기 및 장기 혈당 수치를 허용 가능한 범위 내에서 유지하는 것을 목표로 질병 및 치료,식이 변화 및 운동에 대한 교육의 혜택을 누릴 수 있습니다. 또한, 심혈관 질환의 위험이 더 높기 때문에 혈압을 조절하기 위해 생활 습관 수정을 권장합니다. [110][111]

체중 감소는 당뇨병 전에서 당뇨병 유형 2로의 진행을 방지하거나, 심혈관 질환의 위험을 감소시키거나, 당뇨병 환자의 부분적인 완화를 초래할 수 있습니다. [112][113] 당뇨병을 앓고있는 모든 사람들에게 가장 좋은식이 패턴은 없습니다. [114] 지중해 식단, 저탄수화물 다이어트 또는 DASH 다이어트와 같은 건강한식이 패턴은 종종 권장되지만 증거는 다른 것보다 하나를 뒷받침하지 않습니다. [112][113] ADA에 따르면, "당뇨병을 앓고있는 개인의 전반적인 탄수화물 섭취를 줄이는 것이 혈당을 개선하기위한 가장 큰 증거를 입증했다"고 말하면서, 혈당 목표를 달성 할 수 없거나 항 혈당 약물을 줄이는 것이 우선 순위인 제 2 형 당뇨병을 앓고있는 개인의 경우, 낮은 또는 매우 낮은 탄수화물 다이어트가 실행 가능한 접근법입니다. [113] 제 2 형 당뇨병을 앓고있는 과체중 인 사람들에게는 체중 감량을 달성하는식이 요법이 효과적입니다. [114][115]

약물편집하다

포도당 조절편집하다

당뇨병 치료에 사용되는 대부분의 약물은 다른 메커니즘을 통해 혈당 수치를 낮추는 방식으로 작용합니다. 당뇨병을 앓고있는 사람들이 혈당 조절을 엄격하게 유지할 때 - 혈액의 포도당 수치를 정상 범위 내에서 유지하면 신장 문제 나 눈 문제와 같은 합병증을 덜 경험한다는 광범위한 합의가 있습니다. [116][117] 그러나 이것이 저혈당의 위험이 더 중요 할 수있는 삶의 후반부에 사람들에게 적절하고 비용 효과적인지에 관해서는 논쟁이 있습니다. [118]

항 당뇨병 약물의 다른 클래스의 수가 있습니다. 제 1 형 당뇨병은 인슐린 치료가 필요하며, 이상적으로는 정상적인 인슐린 방출과 가장 밀접하게 일치하는 "기저 볼루스"요법을 사용합니다 : 기저 비율을위한 장기 작용 인슐린과 식사와 함께 단기 작용 인슐린. [119] 제 2 형 당뇨병은 일반적으로 입으로 복용하는 약물 (예 : 메트포르민)으로 치료되지만 일부는 결국 인슐린 또는 GLP-1 작용제로 주사 가능한 치료가 필요합니다. [120]

메트포르민은 사망률을 감소시킨다는 좋은 증거가 있기 때문에 일반적으로 제 2 형 당뇨병의 첫 번째 치료법으로 권장됩니다. [9] 그것은 포도당의 간장의 생산을 감소시킴으로써 작용한다. [121] 주로 입으로 투여되는 여러 다른 약물 그룹도 제 2 형 당뇨병에서 혈당을 감소시킬 수 있습니다. 여기에는 인슐린 방출을 증가시키는 제제 (설포닐우레아), 장내 설탕 흡수를 감소시키는 제제 (acarbose), GLP-1 및 GIP (sitagliptin)와 같은 인크레틴을 불활성화시키는 효소 디펩티딜 펩티다제-4 (DPP-4)를 억제하는 제제, 인슐린에 더 민감하게 만드는 제제 (티아졸리딘디온) 및 소변에서 포도당의 배설을 증가시키는 제제 (SGLT2 억제제)가 포함됩니다. [121] 인슐린이 제 2 형 당뇨병에서 사용될 때, 오래 지속되는 제형은 일반적으로 경구 약물을 계속하면서 초기에 첨가됩니다. [9] 인슐린의 복용량은 포도당 표적에 도달 할 때까지 증가합니다. [9][122]

혈압 강하편집하다

심혈관 질환은 당뇨병과 관련된 심각한 합병증이며, 많은 국제 가이드 라인은 당뇨병 환자에게 140/90mmHg보다 낮은 혈압 치료 목표를 권장합니다. [123] 그러나 낮은 목표가 무엇인지에 관한 제한된 증거 만 있습니다. 2016년 체계적인 검토에 따르면 140mmHg 미만의 대상에 대한 치료에 잠재적 해가 있음을 발견했으며,[124] 2019년 후속 체계적인 검토에서는 부작용의 위험이 증가했지만 혈압을 130~140mmHg 사이로 낮추면 추가적인 이점이 있다는 증거는 발견되지 않았다. [125]

2015 미국 당뇨병 협회 권고 사항은 당뇨병과 알부민뇨를 앓고있는 사람들이 말기 신장 질환, 심혈관 사건 및 사망으로 진행될 위험을 줄이기 위해 레닌 - 안지오텐신 시스템의 억제제를 받아야한다는 것입니다. [126] 안지오텐신 전환 효소 억제제 (ACEIs)가 심혈관 질환을 예방하는 데 안지오텐신 수용체 차단제 (ARBs),[127] 또는 알리 스키 렌과 같은 레닌 - 안지오텐신 시스템의 다른 억제제보다 우수하다는 증거가 있습니다. [128] 보다 최근의 리뷰는 주요 심혈관 및 신장 결과에 대한 ACEI와 ARB의 유사한 효과를 발견했지만. [129] ACEI와 ARB를 결합하면 추가적인 이점을 제공한다는 증거는 없습니다. [129]

아스피린편집하다

당뇨병에서 심혈관 질환을 예방하기 위해 아스피린을 사용하는 것은 논란의 여지가 있습니다. [126] 아스피린은 심혈관 질환의 위험이 높은 사람들의 일부에 의해 권장되지만, 아스피린의 일상적인 사용은 복잡하지 않은 당뇨병의 결과를 개선하는 것으로 밝혀지지 않았습니다. [130] 2015 아스피린 사용에 대한 미국 당뇨병 협회 권고 사항 (전문가 합의 또는 임상 경험에 기초하여)은 심혈관 질환의 중간 위험 (10 년 심혈관 질환 위험, 5-10 %)에있는 당뇨병을 앓고있는 성인에게 저용량 아스피린 사용이 합리적이라는 것입니다. [126] 국립 건강 관리 우수 연구소 (NICE)의 잉글랜드와 웨일즈에 대한 국가 지침은 심혈관 질환이 확인되지 않은 제 1 형 또는 제 2 형 당뇨병 환자에서 아스피린 사용을 금지 할 것을 권고합니다. [119][120]

외과편집하다

비만과 제 2 형 당뇨병을 앓고있는 사람들의 체중 감량 수술은 종종 효과적인 조치입니다. [22] 많은 사람들이 수술 후 약물이 거의 없거나 전혀 없이 정상 혈당 수치를 유지할 수 있으며[131] 장기 사망률이 감소합니다. [132] 그러나 수술로 인한 단기 사망 위험은 1 % 미만입니다. [133] 수술이 적절할 때의 체질량 지수 컷오프는 아직 명확하지 않다. [132] 체중과 혈당을 모두 조절할 수없는 사람들에게이 옵션을 고려하는 것이 좋습니다. [134]

췌장 이식은 신장 이식이 필요한 말기 신장 질환을 포함하여 질병의 심각한 합병증이있는 제 1 형 당뇨병 환자에게 때때로 고려됩니다. [135]

자기 관리 및 지원편집하다

영국과 같은 일반 개업 시스템을 사용하는 국가에서는 주로 병원 밖에서 치료가 이루어질 수 있으며 병원 기반 전문 치료는 합병증, 혈당 조절이 어려운 경우 또는 연구 프로젝트의 경우에만 사용됩니다. 다른 상황에서는 일반 실무자와 전문가가 팀 접근 방식에서 보살핌을 공유합니다. 가정 원격 의료 지원은 효과적인 관리 기술이 될 수 있습니다. [136]

제 2 형 당뇨병을 앓고있는 성인을위한 교육 프로그램을 제공하기 위해 기술을 사용하는 것은 자기 관리를 용이하게하기위한 맞춤형 응답을 수집하기위한 컴퓨터 기반의 자기 관리 개입을 포함합니다. [137] 콜레스테롤, 혈압, 행동 변화 (예 : 신체 활동 수준 및식이 요법), 우울증, 체중 및 건강 관련 삶의 질, 또는 기타 생물학적,인지 적 또는 정서적 결과에 미치는 영향을 뒷받침하는 적절한 증거는 없습니다. [137][138]

역학편집하다

2017년에, 425백만명의 사람들이 전세계적으로 당뇨병을 앓고 있었다,[139] 추정된 382백만명의 사람들에서 2013년의 추정된 사람들[140] 그리고 1980년의 1억 8백만에서 증가했다. [141] 세계 인구의 변화하는 연령 구조를 고려할 때, 당뇨병의 유병률은 성인들 사이에서 8.8 %이며, 1980 년 4.7 %의 거의 두 배에 달한다. [139][141] 유형 2는 케이스의 약 90%를 차지한다. [24][46] 일부 데이터는 비율이 여성과 남성에서 거의 동일하다는 것을 나타내지만,[24] 당뇨병의 남성 과잉은 인슐린 민감성의 성별 관련 차이, 비만 및 지역 체지방 침착의 결과 및 고혈압, 담배 흡연과 같은 기타 기여 요인으로 인해 2 형 발병률이 높은 많은 인구에서 발견되었습니다. 그리고 알코올 섭취. [142][143]

WHO는 당뇨병이 2012 년에 1.5 백만 명의 사망을 초래하여 8 번째 주요 사망 원인으로 추정합니다. [20][141] 그러나 전 세계적으로 또 다른 2.2 백만 명의 사망자는 고혈당과 심혈관 질환 및 기타 관련 합병증 (예 : 신부전)의 위험 증가로 인해 발생했으며, 이는 종종 조기 사망으로 이어지고 종종 당뇨병보다는 사망 진단서의 근본 원인으로 나열됩니다. [141][144] 예를 들어, 2017년에 국제 당뇨병 연맹(IDF)은 당뇨병이 전 세계적으로 4백0십만 명의 사망자를 초래했다고 추정했으며,[139] 모델링을 사용하여 당뇨병에 직접 또는 간접적으로 기인할 수 있는 총 사망자 수를 추정했다. [139]

당뇨병은 전 세계적으로 발생하지만 선진국에서는 더 흔합니다 (특히 제 2 형). 그러나 가장 큰 증가는 당뇨병 사망의 80 % 이상이 발생하는 저소득 및 중산층 국가에서[141] 나타났습니다. [145] 가장 빠른 유병률 증가는 당뇨병을 앓고있는 대부분의 사람들이 아마도 2030 년에 살 아시아와 아프리카에서 발생할 것으로 예상됩니다. [146] 개발 도상국의 비율의 증가는 점점 더 앉아있는 생활 방식, 덜 육체적으로 까다로운 일 및 글로벌 영양 전환을 포함하여 도시화 및 생활 방식의 변화 추세를 따르며, 에너지 밀도가 높지만 영양소가 부족한 음식 섭취 증가로 특징 지어집니다 (종종 설탕과 포화 지방이 많으며 때로는 "서구 스타일"식단이라고도합니다). [141][146] 당뇨병 사례의 세계적인 수는 2017년과 2045년 사이에 48% 증가할 수 있다. [139]

역사편집하다

당뇨병은 기원전 1500년경의 이집트 원고가 "소변을 너무 많이 비우는" 것을 언급하면서 묘사된 최초의 질병 중 하나였다.[147]. [148] Ebers 파피루스는 그러한 경우에 취할 음료에 대한 추천을 포함한다. [149] 최초로 기술된 사례는 제1형 당뇨병인 것으로 여겨진다. [148] 같은 시기에 인도의 의사들은 이 질병을 확인하고 그것을 마두메하 또는 "꿀 소변"으로 분류했는데, 소변이 개미를 끌어당길 것이라고 지적했다. [148][149]

"당뇨병"또는 "통과하다"라는 용어는 기원전 230 년에 멤피스의 그리스 아폴로니우스에 의해 처음 사용되었습니다. [148] 이 병은 로마 제국 시대에는 드문 것으로 간주되었으며, 갈렌은 그의 경력 동안 단지 두 가지 사례 만 보았다고 언급했다. [148] 이것은 아마도 고대인의 식단과 생활 방식 때문일 수도 있고, 질병의 진행된 단계에서 임상 증상이 관찰되었기 때문일 수도 있다. Galen은이 질병을 "소변의 설사"(설사 뇨증)라고 명명했습니다. [150]

당뇨병에 대한 자세한 언급과 함께 가장 오래 살아남은 연구는 카파도키아의 아레테우스 (2 세기 또는 3 세기 초)의 작품입니다. 그는 "공압 학교"의 신념을 반영하여 습기와 추위에 기인 한 질병의 증상과 경과를 설명했습니다. 그는 당뇨병과 다른 질병 사이의 상관 관계를 가정하고 과도한 갈증을 유발하는 뱀 물린으로부터의 감별 진단에 대해 논의했습니다. 그의 작품은 베니스에서 첫 번째 라틴어 판이 출판 된 1552 년까지 서양에서 알려지지 않았습니다. [150]

두 가지 유형의 당뇨병은 인도 의사 인 Sushruta와 Charaka가 400-500 CE에서 처음으로 별도의 조건으로 확인되었으며 한 유형은 청소년과 관련이 있고 다른 유형은 과체중과 관련이 있습니다. [148] 효과적인 치료는 캐나다인 Frederick Banting과 Charles Herbert Best가 1921 년과 1922 년에 인슐린을 분리하고 정제 한 20 세기 초반까지 개발되지 않았습니다. [148] 이것은 1940년대에 지속형 인슐린 NPH의 발달로 이어졌다.[148]

어원학편집하다

당뇨병이라는 단어 (/ˌdaɪ. əˈb iː tiːz/ or /ˌdaɪ. əˈbiːtɪs/)는 라틴어 diabētēs에서 유래했으며, 이는 고대 그리스어 διαβήτης (diabētēs)에서 유래했으며, 문자 그대로 "통행인"을 의미합니다. 사이펀". [151] 고대 그리스 의사 카파도키아의 아레테우스(Aretaeus of Cappadocia, 기원전 1세기 경)는 이 단어를 "소변의 과도한 배출"이라는 의도된 의미와 함께 이 질병의 이름으로 사용했다. [152][153] 궁극적으로, 이 단어는 그리스어 διαβαίνειν(디아바이닌)에서 유래한 것으로, "통과하다"를 의미하고,[151] δια-(디아-)로 구성되어 있으며, "통과하다"를 의미하고, βαίνειν(bainein)는 "가다"를 의미한다. [152] "당뇨병"이라는 단어는 1425년경에 쓰여진 의학 텍스트에서 당뇨병 형태로 영어로 처음 기록된다.

The word mellitus (/məˈlaɪtəs/ or /ˈmɛlɪtəs/) comes from the classical Latin word mellītus, meaning "mellite"[154] (i.e. sweetened with honey;[154] honey-sweet[155]). The Latin word comes from mell-, which comes from mel, meaning "honey";[154][155] sweetness;[155] pleasant thing,[155] and the suffix -ītus,[154] whose meaning is the same as that of the English suffix "-ite".[156] It was Thomas Willis who in 1675 added "mellitus" to the word "diabetes" as a designation for the disease, when he noticed the urine of a person with diabetes had a sweet taste (glycosuria). This sweet taste had been noticed in urine by the ancient Greeks, Chinese, Egyptians, Indians, and Persians[citation needed].

Society and cultureEdit

The 1989 "St. Vincent Declaration"[157][158] was the result of international efforts to improve the care accorded to those with diabetes. Doing so is important not only in terms of quality of life and life expectancy but also economically – expenses due to diabetes have been shown to be a major drain on health – and productivity-related resources for healthcare systems and governments.

Several countries established more and less successful national diabetes programmes to improve treatment of the disease.[159]

People with diabetes who have neuropathic symptoms such as numbness or tingling in feet or hands are twice as likely to be unemployed as those without the symptoms.[160]

In 2010, diabetes-related emergency room (ER) visit rates in the United States were higher among people from the lowest income communities (526 per 10,000 population) than from the highest income communities (236 per 10,000 population). Approximately 9.4% of diabetes-related ER visits were for the uninsured.[161]

NamingEdit

The term "type 1 diabetes" has replaced several former terms, including childhood-onset diabetes, juvenile diabetes, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Likewise, the term "type 2 diabetes" has replaced several former terms, including adult-onset diabetes, obesity-related diabetes, and noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Beyond these two types, there is no agreed-upon standard nomenclature.[162]

Diabetes mellitus is also occasionally known as "sugar diabetes" to differentiate it from diabetes insipidus.[163]

Other animalsEdit

In animals, diabetes is most commonly encountered in dogs and cats. Middle-aged animals are most commonly affected. Female dogs are twice as likely to be affected as males, while according to some sources, male cats are more prone than females. In both species, all breeds may be affected, but some small dog breeds are particularly likely to develop diabetes, such as Miniature Poodles.[164]

Feline diabetes is strikingly similar to human type 2 diabetes. The Burmese, Russian Blue, Abyssinian, and Norwegian Forest cat breeds are at higher risk than other breeds. Overweight cats are also at higher risk.[165]

The symptoms may relate to fluid loss and polyuria, but the course may also be insidious. Diabetic animals are more prone to infections. The long-term complications recognized in humans are much rarer in animals. The principles of treatment (weight loss, oral antidiabetics, subcutaneous insulin) and management of emergencies (e.g. ketoacidosis) are similar to those in humans.[164]

ReferencesEdit

- ^ "Diabetes Blue Circle Symbol". International Diabetes Federation. 17 March 2006. Archived from the original on 5 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Diabetes Fact sheet N°312". WHO. October 2013. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN (July 2009). "Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes". Diabetes Care. 32 (7): 1335–1343. doi:10.2337/dc09-9032. PMC 2699725. PMID 19564476.

- ^ Krishnasamy S, Abell TL (July 2018). "Diabetic Gastroparesis: Principles and Current Trends in Management". Diabetes Therapy. 9 (Suppl 1): 1–42. doi:10.1007/s13300-018-0454-9. PMC 6028327. PMID 29934758.

- ^ a b Saedi E, Gheini MR, Faiz F, Arami MA (September 2016). "Diabetes mellitus and cognitive impairments". World Journal of Diabetes. 7 (17): 412–422. doi:10.4239/wjd.v7.i17.412. PMC 5027005. PMID 27660698.

- ^ a b Chiang JL, Kirkman MS, Laffel LM, Peters AL (July 2014). "Type 1 diabetes through the life span: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association". Diabetes Care. 37 (7): 2034–2054. doi:10.2337/dc14-1140. PMC 5865481. PMID 24935775.

- ^ "Causes of Diabetes". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. June 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ Heinrich J, Yang BY (January 2020). "Ambient air pollution and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Environmental Research. 180: 108817. Bibcode:2020ER....180j8817Y. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2019.108817. PMID 31627156. S2CID 204787461. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ripsin CM, Kang H, Urban RJ (January 2009). "Management of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus" (PDF). American Family Physician. 79 (1): 29–36. PMID 19145963. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-05.

- ^ Brutsaert EF (February 2017). "Drug Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus". MSDManuals.com. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "IDF DIABETES ATLAS Ninth Edition 2019" (PDF). www.diabetesatlas.org. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "About diabetes". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Shoback DG, Gardner D, eds. (2011). "Chapter 17". Greenspan's basic & clinical endocrinology (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-162243-1.

- ^ "What is Diabetes? | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ Norman A, Henry H (2015). Hormones. Elsevier. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9780123694447.

- ^ "Type 1 diabetes - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ RSSDI textbook of diabetes mellitus (Revised 2nd ed.). Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 2012. p. 235. ISBN 978-93-5025-489-9. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015.

- ^ "Type 2 diabetes - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ "Gestational diabetes - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ a b "The top 10 causes of death Fact sheet N°310". World Health Organization. October 2013. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017.

- ^ Rippe RS, Irwin JM, eds. (2010). Manual of intensive care medicine (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 549. ISBN 978-0-7817-9992-8.

- ^ a b Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL, Gospodarevskaya E, Loveman E, Baxter L, Clegg AJ (September 2009). "The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment. 13 (41): 1–190, 215–357, iii–iv. doi:10.3310/hta13410. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30064294. PMID 19726018.

- ^ Cash J (2014). Family Practice Guidelines (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-8261-6875-7. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–2196. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- ^ "What is Diabetes?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "The top 10 causes of death". www.who.int. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ American Diabetes Association (May 2018). "Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017". Diabetes Care. 41 (5): 917–928. doi:10.2337/dci18-0007. PMC 5911784. PMID 29567642.

- ^ "Deaths and Cost | Data & Statistics | Diabetes | CDC". cdc.gov. 20 February 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Cooke DW, Plotnick L (November 2008). "Type 1 diabetes mellitus in pediatrics". Pediatrics in Review. 29 (11): 374–84, quiz 385. doi:10.1542/pir.29-11-374. PMID 18977856. S2CID 20528207.

- ^ "WHO | Diabetes mellitus". WHO. Archived from the original on June 11, 2004. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- ^ Rockefeller JD (2015). Diabetes: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment and Prevention. ISBN 978-1-5146-0305-5.

- ^ a b Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN (July 2009). "Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes". Diabetes Care. 32 (7): 1335–1343. doi:10.2337/dc09-9032. PMC 2699725. PMID 19564476. Archived from the original on 2016-06-25.

- ^ Kenny C (April 2014). "When hypoglycemia is not obvious: diagnosing and treating under-recognized and undisclosed hypoglycemia". Primary Care Diabetes. 8 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.09.002. PMID 24100231.

- ^ Verrotti A, Scaparrotta A, Olivieri C, Chiarelli F (December 2012). "Seizures and type 1 diabetes mellitus: current state of knowledge". European Journal of Endocrinology. 167 (6): 749–758. doi:10.1530/EJE-12-0699. PMID 22956556.

- ^ "Symptoms of Low Blood Sugar". WebMD. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ "Glucagon–Injection side effects, medical uses, and drug interactions". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ "Diabetes - long-term effects". betterhealth.vic.gov.au.

- ^ Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, et al. (June 2010). "Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies". Lancet. 375 (9733): 2215–2222. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60484-9. PMC 2904878. PMID 20609967.

- ^ O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. (January 2013). "2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 127 (4): e362–e425. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. PMID 23247304.

- ^ Papatheodorou K, Banach M, Bekiari E, Rizzo M, Edmonds M (11 March 2018). "Complications of Diabetes 2017". Journal of Diabetes Research. 2018: 3086167. doi:10.1155/2018/3086167. PMC 5866895. PMID 29713648.

- ^ Kompaniyets L, Pennington AF, Goodman AB, Rosenblum HG, Belay B, Ko JY, et al. (July 2021). "Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020-March 2021". Preventing Chronic Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18: E66. doi:10.5888/pcd18.210123. PMC 8269743. PMID 34197283.

- ^ a b c d "Diabetes Programme". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Diabetes – eye care: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ Cukierman T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD (December 2005). "Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes--systematic overview of prospective observational studies". Diabetologia. 48 (12): 2460–2469. doi:10.1007/s00125-005-0023-4. PMID 16283246.

- ^ Yang Y, Hu X, Zhang Q, Zou R (November 2016). "Diabetes mellitus and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Age and Ageing. 45 (6): 761–767. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw140. PMID 27515679.

- ^ a b c Williams textbook of endocrinology (12th ed.). Elsevier/Saunders. 2011. pp. 1371–1435. ISBN 978-1-4377-0324-5.

- ^ Lambert P, Bingley PJ (2002). "What is Type 1 Diabetes?". Medicine. 30: 1–5. doi:10.1383/medc.30.1.1.28264.

- ^ Skov J, Eriksson D, Kuja-Halkola R, Höijer J, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Svensson AM, et al. (May 2020). "Co-aggregation and heritability of organ-specific autoimmunity: a population-based twin study". European Journal of Endocrinology. 182 (5): 473–480. doi:10.1530/EJE-20-0049. PMC 7182094. PMID 32229696.

- ^ Hyttinen V, Kaprio J, Kinnunen L, Koskenvuo M, Tuomilehto J (April 2003). "Genetic liability of type 1 diabetes and the onset age among 22,650 young Finnish twin pairs: a nationwide follow-up study". Diabetes. 52 (4): 1052–1055. doi:10.2337/diabetes.52.4.1052. PMID 12663480.

- ^ Condon J, Shaw JE, Luciano M, Kyvik KO, Martin NG, Duffy DL (February 2008). "A study of diabetes mellitus within a large sample of Australian twins" (PDF). Twin Research and Human Genetics. 11 (1): 28–40. doi:10.1375/twin.11.1.28. PMID 18251672. S2CID 18072879.

- ^ Willemsen G, Ward KJ, Bell CG, Christensen K, Bowden J, Dalgård C, et al. (December 2015). "The Concordance and Heritability of Type 2 Diabetes in 34,166 Twin Pairs From International Twin Registers: The Discordant Twin (DISCOTWIN) Consortium". Twin Research and Human Genetics. 18 (6): 762–771. doi:10.1017/thg.2015.83. PMID 26678054. S2CID 17854531.

- ^ Mobasseri M, Shirmohammadi M, Amiri T, Vahed N, Hosseini Fard H, Ghojazadeh M (2020-03-30). "Prevalence and incidence of type 1 diabetes in the world: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Health Promotion Perspectives. 10 (2): 98–115. doi:10.34172/hpp.2020.18. PMC 7146037. PMID 32296622.

- ^ Lin X, Xu Y, Pan X, Xu J, Ding Y, Sun X, et al. (September 2020). "Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: an analysis from 1990 to 2025". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 14790. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1014790L. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71908-9. PMC 7478957. PMID 32901098.

- ^ Tinajero MG, Malik VS (September 2021). "An Update on the Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes: A Global Perspective". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 50 (3): 337–355. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2021.05.013. PMID 34399949.

- ^ "Classification of Diabetes mellitus 2019". WHO. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- ^ Tuomi T, Santoro N, Caprio S, Cai M, Weng J, Groop L (March 2014). "The many faces of diabetes: a disease with increasing heterogeneity". Lancet. 383 (9922): 1084–1094. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62219-9. PMID 24315621. S2CID 12679248.

- ^ Rother KI (April 2007). "Diabetes treatment--bridging the divide". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (15): 1499–1501. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078030. PMC 4152979. PMID 17429082.

- ^ a b "Diabetes Mellitus (DM): Diabetes Mellitus and Disorders of Carbohydrate Metabolism: Merck Manual Professional". Merck Publishing. April 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-07-28. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ Dorner M, Pinget M, Brogard JM (May 1977). "[Essential labile diabetes (author's transl)]". Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 119 (19): 671–674. PMID 406527.

- ^ a b Petzold A, Solimena M, Knoch KP (October 2015). "Mechanisms of Beta Cell Dysfunction Associated With Viral Infection". Current Diabetes Reports (Review). 15 (10): 73. doi:10.1007/s11892-015-0654-x. PMC 4539350. PMID 26280364. So far, none of the hypotheses accounting for virus-induced beta cell autoimmunity has been supported by stringent evidence in humans, and the involvement of several mechanisms rather than just one is also plausible.

- ^ Butalia S, Kaplan GG, Khokhar B, Rabi DM (December 2016). "Environmental Risk Factors and Type 1 Diabetes: Past, Present, and Future". Canadian Journal of Diabetes (Review). 40 (6): 586–593. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.05.002. PMID 27545597.

- ^ Serena G, Camhi S, Sturgeon C, Yan S, Fasano A (August 2015). "The Role of Gluten in Celiac Disease and Type 1 Diabetes". Nutrients. 7 (9): 7143–7162. doi:10.3390/nu7095329. PMC 4586524. PMID 26343710.

- ^ Visser J, Rozing J, Sapone A, Lammers K, Fasano A (May 2009). "Tight junctions, intestinal permeability, and autoimmunity: celiac disease and type 1 diabetes paradigms". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1165 (1): 195–205. Bibcode:2009NYASA1165..195V. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04037.x. PMC 2886850. PMID 19538307.

- ^ Laugesen E, Østergaard JA, Leslie RD (July 2015). "Latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult: current knowledge and uncertainty". Diabetic Medicine. 32 (7): 843–852. doi:10.1111/dme.12700. PMC 4676295. PMID 25601320.

- ^ American Diabetes Association (January 2017). "2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes". Diabetes Care. 40 (Suppl 1): S11–S24. doi:10.2337/dc17-S005. PMID 27979889.

- ^ Carris NW, Magness RR, Labovitz AJ (February 2019). "Prevention of Diabetes Mellitus in Patients With Prediabetes". The American Journal of Cardiology. 123 (3): 507–512. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.10.032. PMC 6350898. PMID 30528418.

- ^ a b Risérus U, Willett WC, Hu FB (January 2009). "Dietary fats and prevention of type 2 diabetes". Progress in Lipid Research. 48 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2008.10.002. PMC 2654180. PMID 19032965.

- ^ Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Hu FB (March 2010). "Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk". Circulation. 121 (11): 1356–1364. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185. PMC 2862465. PMID 20308626.

- ^ Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Willett WC, Hu FB (November 2010). "Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis". Diabetes Care. 33 (11): 2477–2483. doi:10.2337/dc10-1079. PMC 2963518. PMID 20693348.

- ^ Hu EA, Pan A, Malik V, Sun Q (March 2012). "White rice consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis and systematic review". BMJ. 344: e1454. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1454. PMC 3307808. PMID 22422870.

- ^ Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT (July 2012). "Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy". Lancet. 380 (9838): 219–229. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. PMC 3645500. PMID 22818936.

- ^ Huang H, Yan P, Shan Z, Chen S, Li M, Luo C, et al. (November 2015). "Adverse childhood experiences and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Metabolism. 64 (11): 1408–1418. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.08.019. PMID 26404480.

- ^ Zhang Y, Liu Y, Su Y, You Y, Ma Y, Yang G, et al. (November 2017). "The metabolic side effects of 12 antipsychotic drugs used for the treatment of schizophrenia on glucose: a network meta-analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 17 (1): 373. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1539-0. PMC 5698995. PMID 29162032.

- ^ a b "National Diabetes Clearinghouse (NDIC): National Diabetes Statistics 2011". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b Soldavini J (November 2019). "Krause's Food & The Nutrition Care Process". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 51 (10): 1225. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2019.06.022. ISSN 1499-4046. S2CID 209272489.

- ^ "Managing & Treating Gestational Diabetes | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- ^ Tarvonen M, Hovi P, Sainio S, Vuorela P, Andersson S, Teramo K (November 2021). "Intrapartal cardiotocographic patterns and hypoxia-related perinatal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus". Acta Diabetologica. 58 (11): 1563–1573. doi:10.1007/s00592-021-01756-0. PMC 8505288. PMID 34151398. S2CID 235487220.

- ^ National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (February 2015). "Intrapartum care". Diabetes in Pregnancy: Management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK).

- ^ "Monogenic Forms of Diabetes". National institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases. US NIH. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Thanabalasingham G, Owen KR (2011년 10월). "젊은 (MODY)의 성숙 발병 당뇨병의 진단 및 관리". BMJ입니다. 343 (oct19 3): d6044. 도이 : 10.1136 / bmj.d6044. PMID 22012810. S2CID 44891167.

- ^ a b "당뇨병과 그 합병증의 정의, 진단 및 분류"(PDF). 세계 보건기구. 1999. 2003년 3월 8일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서(PDF).

- ^ Cleland SJ, Fisher BM, Colhoun HM, Sattar N, Petrie JR (July 2013). "제 1 형 당뇨병의 인슐린 저항성 : '이중 당뇨병'이란 무엇이며 위험은 무엇입니까?". 디아베톨로지아. 국립 의학 도서관. 56 (7): 1462–1470. doi : 10.1007 / s00125-013-2904-2. PMC 3671104. PMID 23613085.

- ^ 달리 명시되지 않는 한, 참고문헌은: 미첼, 리처드 셰퍼드의 표 20-5; 쿠마르, 비나이; 아바스, 아불 케이; 파우스토, 넬슨 (2007). 로빈스 기본 병리학 (8th ed.). 필라델피아 : 사운더스. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^ Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, et al. (2010년 2월). "스타틴과 사고 당뇨병의 위험 : 무작위 스타틴 시험의 공동 메타 분석". 랜싯. 375 (9716): 735–742. 도이 : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (09) 61965-6. PMID 20167359. S2CID 11544414.

- ^ "인슐린 기본". 미국 당뇨병 협회. 2014년 2월 14일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2014년 4월 24일에 확인함.

- ^ a b c d Shoback DG, Gardner D, eds. (2011). Greenspan's basic & clinical endocrinology (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-162243-1.

- ^ Barrett KE, et al. (2012). Ganong's review of medical physiology (24th ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-178003-2.

- ^ Murray RK, et al. (2012). Harper's illustrated biochemistry (29th ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-176576-3.

- ^ Mogotlane S (2013). Juta's Complete Textbook of Medical Surgical Nursing. Cape Town: Juta. p. 839.

- ^ "Summary of revisions for the 2010 Clinical Practice Recommendations". Diabetes Care. 33 (Suppl 1): S3. January 2010. doi:10.2337/dc10-S003. PMC 2797388. PMID 20042773. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: Report of a WHO/IDF consultation (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2006. p. 21. ISBN 978-92-4-159493-6.

- ^ Vijan S (March 2010). "In the clinic. Type 2 diabetes". Annals of Internal Medicine. 152 (5): ITC31-15, quiz ITC316. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-5-201003020-01003. PMID 20194231.

- ^ Saydah SH, Miret M, Sung J, Varas C, Gause D, Brancati FL (August 2001). "Postchallenge hyperglycemia and mortality in a national sample of U.S. adults". Diabetes Care. 24 (8): 1397–1402. doi:10.2337/diacare.24.8.1397. PMID 11473076.

- ^ Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation (PDF). World Health Organization. 2006. p. 21. ISBN 978-92-4-159493-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2012.

- ^ Santaguida PL, Balion C, Hunt D, Morrison K, Gerstein H, Raina P, et al. (August 2005). "Diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (128): 1–11. PMC 4780988. PMID 16194123. Archived from the original on 16 September 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ^ Bartoli E, Fra GP, Carnevale Schianca GP (February 2011). "The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) revisited". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 22 (1): 8–12. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2010.07.008. PMID 21238885.

- ^ Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, Matsushita K, Wagenknecht L, Pankow J, et al. (March 2010). "Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (9): 800–811. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.589.1658. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908359. PMC 2872990. PMID 20200384.

- ^ "Tackling risk factors for type 2 diabetes in adolescents: PRE-STARt study in Euskadi". Anales de Pediatria. Anales de Pediatría. 95 (3): 186–196. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2020.11.001. PMID 33388268.

- ^ Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, Mumford JE, Afshin A, Estep K, et al. (August 2016). "Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". BMJ. 354: i3857. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3857. PMC 4979358. PMID 27510511.

- ^ a b "Simple Steps to Preventing Diabetes". The Nutrition Source. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 18 September 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014.

- ^ Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J (December 2007). "Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 298 (22): 2654–2664. doi:10.1001/jama.298.22.2654. PMID 18073361.

- ^ "Chronic diseases and their common risk factors" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-17. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Toumpanakis A, Turnbull T, Alba-Barba I (2018-10-30). "Effectiveness of plant-based diets in promoting well-being in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review". BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care. 6 (1): e000534. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2018-000534. PMC 6235058. PMID 30487971.

- ^ Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al. (December 2005). "Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (25): 2643–2653. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052187. PMC 2637991. PMID 16371630.

- ^ "The effect of intensive diabetes therapy on the development and progression of neuropathy. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group". Annals of Internal Medicine. 122 (8): 561–568. April 1995. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-122-8-199504150-00001. PMID 7887548. S2CID 24754081.

- ^ Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, Horwitch C, Barry MJ, Forciea MA, et al. (April 2018). "Hemoglobin A1c Targets for Glycemic Control With Pharmacologic Therapy for Nonpregnant Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Guidance Statement Update From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 168 (8): 569–576. doi:10.7326/M17-0939. PMID 29507945.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 66: Type 2 diabetes. London, 2008.

- ^ Cavanagh PR (2004). "Therapeutic footwear for people with diabetes". Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 20 (Suppl 1): S51–S55. doi:10.1002/dmrr.435. PMID 15150815. S2CID 33268734.

- ^ McBain H, Mulligan K, Haddad M, Flood C, Jones J, Simpson A, et al. (Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group) (April 2016). "Self management interventions for type 2 diabetes in adult people with severe mental illness". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011361. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011361.pub2. PMID 27120555.

- ^ Haw JS, Galaviz KI, Straus AN, Kowalski AJ, Magee MJ, Weber MB, et al. (December 2017). "Long-term Sustainability of Diabetes Prevention Approaches: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials". JAMA Internal Medicine. 177 (12): 1808–1817. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6040. PMC 5820728. PMID 29114778.

- ^ Mottalib A, Kasetty M, Mar JY, Elseaidy T, Ashrafzadeh S, Hamdy O (August 2017). "Weight Management in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes and Obesity". Current Diabetes Reports. 17 (10): 92. doi:10.1007/s11892-017-0918-8. PMC 5569154. PMID 28836234.

- ^ a b American Diabetes Association (January 2019). "5. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019". Diabetes Care. 42 (Suppl 1): S46–S60. doi:10.2337/dc19-S005. PMID 30559231.

- ^ a b c Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, Garvey WT, Lau KH, MacLeod J, et al. (May 2019). "Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report". Diabetes Care (Professional society guidelines). 42 (5): 731–754. doi:10.2337/dci19-0014. PMC 7011201. PMID 31000505.

- ^ a b Emadian A, Andrews RC, England CY, Wallace V, Thompson JL (November 2015). "The effect of macronutrients on glycaemic control: a systematic review of dietary randomised controlled trials in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes in which there was no difference in weight loss between treatment groups". The British Journal of Nutrition. 114 (10): 1656–1666. doi:10.1017/S0007114515003475. PMC 4657029. PMID 26411958.

- ^ Grams J, Garvey WT (June 2015). "Weight Loss and the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Using Lifestyle Therapy, Pharmacotherapy, and Bariatric Surgery: Mechanisms of Action". Current Obesity Reports. 4 (2): 287–302. doi:10.1007/s13679-015-0155-x. PMID 26627223. S2CID 207474124.

- ^ Rosberger DF (December 2013). "Diabetic retinopathy: current concepts and emerging therapy". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 42 (4): 721–745. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2013.08.001. PMID 24286948.

- ^ MacIsaac RJ, Jerums G, Ekinci EI (March 2018). "Glycemic Control as Primary Prevention for Diabetic Kidney Disease". Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 25 (2): 141–148. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2017.11.003. PMID 29580578.

- ^ Pozzilli P, Strollo R, Bonora E (March 2014). "One size does not fit all glycemic targets for type 2 diabetes". Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 5 (2): 134–141. doi:10.1111/jdi.12206. PMC 4023573. PMID 24843750.

- ^ a b "Type 1 diabetes in adults: diagnosis and management". www.nice.org.uk. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 26 August 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Type 2 diabetes in adults: management". www.nice.org.uk. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b Krentz AJ, Bailey CJ (2005). "Oral antidiabetic agents: current role in type 2 diabetes mellitus". Drugs. 65 (3): 385–411. doi:10.2165/00003495-200565030-00005. PMID 15669880. S2CID 29670619.

- ^ Consumer Reports; American College of Physicians (April 2012), "Choosing a type 2 diabetes drug – Why the best first choice is often the oldest drug" (PDF), High Value Care, Consumer Reports, archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2014, retrieved August 14, 2012

- ^ Mitchell S, Malanda B, Damasceno A, Eckel RH, Gaita D, Kotseva K, et al. (September 2019). "A Roadmap on the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Among People Living With Diabetes". Global Heart. 14 (3): 215–240. doi:10.1016/j.gheart.2019.07.009. PMID 31451236.

- ^ Brunström M, Carlberg B (February 2016). "Effect of antihypertensive treatment at different blood pressure levels in patients with diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses". BMJ. 352: i717. doi:10.1136/bmj.i717. PMC 4770818. PMID 26920333.

- ^ Brunström M, Carlberg B (September 2019). "Benefits and harms of lower blood pressure treatment targets: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials". BMJ Open. 9 (9): e026686. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026686. PMC 6773352. PMID 31575567.

- ^ a b c Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, Bray GA, Burke LE, de Boer IH, et al. (September 2015). "Update on Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Light of Recent Evidence: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association". Diabetes Care. 38 (9): 1777–1803. doi:10.2337/dci15-0012. PMC 4876675. PMID 26246459.

- ^ Cheng J, Zhang W, Zhang X, Han F, Li X, He X, et al. (May 2014). "Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular deaths, and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (5): 773–785. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.348. PMID 24687000.

- ^ Zheng SL, Roddick AJ, Ayis S (September 2017). "Effects of aliskiren on mortality, cardiovascular outcomes and adverse events in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease or risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 13,395 patients". Diabetes & Vascular Disease Research. 14 (5): 400–406. doi:10.1177/1479164117715854. PMC 5600262. PMID 28844155.

- ^ a b Catalá-López F, Macías Saint-Gerons D, González-Bermejo D, Rosano GM, Davis BR, Ridao M, et al. (March 2016). "Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes of Renin-Angiotensin System Blockade in Adult Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analyses". PLOS Medicine. 13 (3): e1001971. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001971. PMC 4783064. PMID 26954482.

- ^ Pignone M, Alberts MJ, Colwell JA, Cushman M, Inzucchi SE, Mukherjee D, et al. (June 2010). "Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, a scientific statement of the American Heart Association, and an expert consensus document of the American College of Cardiology Foundation". Diabetes Care. 33 (6): 1395–1402. doi:10.2337/dc10-0555. PMC 2875463. PMID 20508233.

- ^ Frachetti KJ, Goldfine AB (April 2009). "Bariatric surgery for diabetes management". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 16 (2): 119–124. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32832912e7. PMID 19276974. S2CID 31797748.

- ^ a b Schulman AP, del Genio F, Sinha N, Rubino F (September–October 2009). ""Metabolic" surgery for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus". Endocrine Practice. 15 (6): 624–631. doi:10.4158/EP09170.RAR. PMID 19625245.

- ^ Colucci RA (January 2011). "Bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes: a viable option". Postgraduate Medicine. 123 (1): 24–33. doi:10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2242. PMID 21293081. S2CID 207551737.

- ^ Dixon JB, le Roux CW, Rubino F, Zimmet P (June 2012). "Bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes". Lancet. 379 (9833): 2300–2311. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60401-2. PMID 22683132. S2CID 5198462.

- ^ "Pancreas Transplantation". American Diabetes Association. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Polisena J, Tran K, Cimon K, Hutton B, McGill S, Palmer K (October 2009). "Home telehealth for diabetes management: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 11 (10): 913–930. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01057.x. PMID 19531058. S2CID 44260857.

- ^ a b Pal K, Eastwood SV, Michie S, Farmer AJ, Barnard ML, Peacock R, et al. (Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group) (March 2013). "Computer-based diabetes self-management interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD008776. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008776.pub2. PMC 6486319. PMID 23543567.

- ^ Wei I, Pappas Y, Car J, Sheikh A, Majeed A, et al. (Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group) (December 2011). "Computer-assisted versus oral-and-written dietary history taking for diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008488. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008488.pub2. PMC 6486022. PMID 22161430.

- ^ a b c d e Elflein J (10 December 2019). Estimated number diabetics worldwide.

- ^ Shi Y, Hu FB (June 2014). "The global implications of diabetes and cancer". Lancet. 383 (9933): 1947–1948. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60886-2. PMID 24910221. S2CID 7496891.

- ^ a b c d e f "Global Report on Diabetes" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Gale EA, Gillespie KM (January 2001). "Diabetes and gender". Diabetologia. 44 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1007/s001250051573. PMID 11206408.

- ^ Meisinger C, Thorand B, Schneider A, Stieber J, Döring A, Löwel H (January 2002). "Sex differences in risk factors for incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the MONICA Augsburg cohort study". Archives of Internal Medicine. 162 (1): 82–89. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.1.82. PMID 11784224.

- ^ Public Health Agency of Canada, Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa, 2011.

- ^ Mathers CD, Loncar D (November 2006). "Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030". PLOS Medicine. 3 (11): e442. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. PMC 1664601. PMID 17132052.

- ^ a b Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H (May 2004). "Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030". Diabetes Care. 27 (5): 1047–1053. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. PMID 15111519.

- ^ Ripoll BC, Leutholtz I (2011-04-25). Exercise and disease management (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4398-2759-8. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Poretsky L, ed. (2009). Principles of diabetes mellitus (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-387-09840-1. Archived from the original on 2016-04-04.

- ^ a b Roberts J (2015). "Sickening sweet". Distillations. Vol. 1, no. 4. pp. 12–15. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ a b Laios K, Karamanou M, Saridaki Z, Androutsos G (2012). "Aretaeus of Cappadocia and the first description of diabetes" (PDF). Hormones. 11 (1): 109–113. doi:10.1007/BF03401545. PMID 22450352. S2CID 4730719. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-04.

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary. diabetes. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ a b Harper D (2001–2010). "Online Etymology Dictionary. diabetes.". Archived from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Aretaeus, De causis et signis acutorum morborum (lib. 2), Κεφ. β. περὶ Διαβήτεω (Chapter 2, On Diabetes, Greek original) Archived 2014-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, on Perseus

- ^ a b c d Oxford English Dictionary. mellite. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ a b c d "MyEtimology. mellitus.". Archived from the original on 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. -ite. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA (2008). The New Public Health, Second Edition. New York: Academic Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-12-370890-8.

- ^ Piwernetz K, Home PD, Snorgaard O, Antsiferov M, Staehr-Johansen K, Krans M (May 1993). "세인트 빈센트 선언의 목표와 당뇨병 치료의 품질 관리 구현 모니터링 : DIABCARE 이니셔티브. 세인트 빈센트 선언 운영위원회의 DIABCARE 모니터링 그룹". 당뇨병 의학. 10 (4): 371–377. doi : 10.1111 / j.1464-5491.1993.tb00083.x. PMID 8508624. S2CID 9931183.

- ^ Dubois H, Bankauskaite V (2005). "유럽의 제 2 형 당뇨병 프로그램"(PDF). 유로 옵저버. 7 (2): 5–6. 2012년 10월 24일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서(PDF).

- ^ Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hirsch AG, Brandenburg NA (June 2007). "미국 노동력의 당뇨병 및 당뇨병 성 신경 병증 성 통증으로 인한 생산 시간과 비용 손실". 직업 및 환경 의학 저널. 49 (6): 672–679. 도이 : 10.1097 / JOM.0b013e318065b83a. PMID 17563611. S2CID 21487348.

- ^ 워싱턴 R.E.; 앤드류스 R.M.; Mutter R.L. (2013년 11월). "당뇨병을 앓고있는 성인을위한 응급실 방문, 2010". HCUP 통계 개요 #167. Rockville MD : 건강 관리 연구 및 품질 기관. 2013년 12월 3일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ^ "제 1 형 대 제 2 형 당뇨병 차이점 : 어느 것이 더 나쁜가?". MedicineNet. 2021년 3월 21일에 확인함.

- ^ 파커 케이 (2008). 당뇨병과 함께 생활. 뉴욕 : 파일에 대한 사실. 143쪽. ISBN 978-1-4381-2108-6.

- ^ a b "당뇨병". 머크 수의학 매뉴얼, 제 9 판 (온라인 버전). 2005. 2011년 9월 27일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2011년 10월 23일에 확인함.

- ^ Öhlund M. Feline 당뇨병 역학 및 병인에 대한 측면 (PDF). Acta Universitatis agriculturae Sueciae. ISBN 978-91-7760-067-1.

외부 링크편집하다

- 컬리의 당뇨병

- 미국 당뇨병 협회

- IDF 당뇨병 아틀라스

- 국가 당뇨병 교육 프로그램

- 당뇨병 의료 ADA의 표준 2019

- 폴론스키 KS (2012년 10월). "당뇨병에서 지난 200 년". 뉴 잉글랜드 의학 저널. 367 (14): 1332–1340. 도이 : 10.1056 / NEJMra1110560. PMID 23034021. S2CID 9456681.

- "당뇨병". 메드라인플러스. 미국 국립 의학 도서관.

'Health 건강 > Diabetes Core 당뇨' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 당뇨의 이해 -이기는 길 (0) | 2022.09.06 |

|---|---|

| 당뇨에는 물이 최고 (0) | 2022.09.06 |

| 당뇨와 발건강 (0) | 2022.09.06 |

| 당뇨와 COVID-19 (0) | 2022.09.06 |

| 당뇨와 건강생활 (0) | 2022.09.06 |